Should the Threat of Lawsuits Keep You from Practicing Church Discipline?

May 15, 2025

May 15, 2025

In 1892, a salacious disciplinary case enveloped a church and scandalized a city. It started with a 27-year-old man named Warren C. Brundage. Brundage was well known to the church. His mother, Alice P. Brundage, had been a member since 1880, and Brundage himself had joined Metropolitan Baptist Church (now Capitol Hill Baptist Church) by baptism during the protracted meetings of 1885.

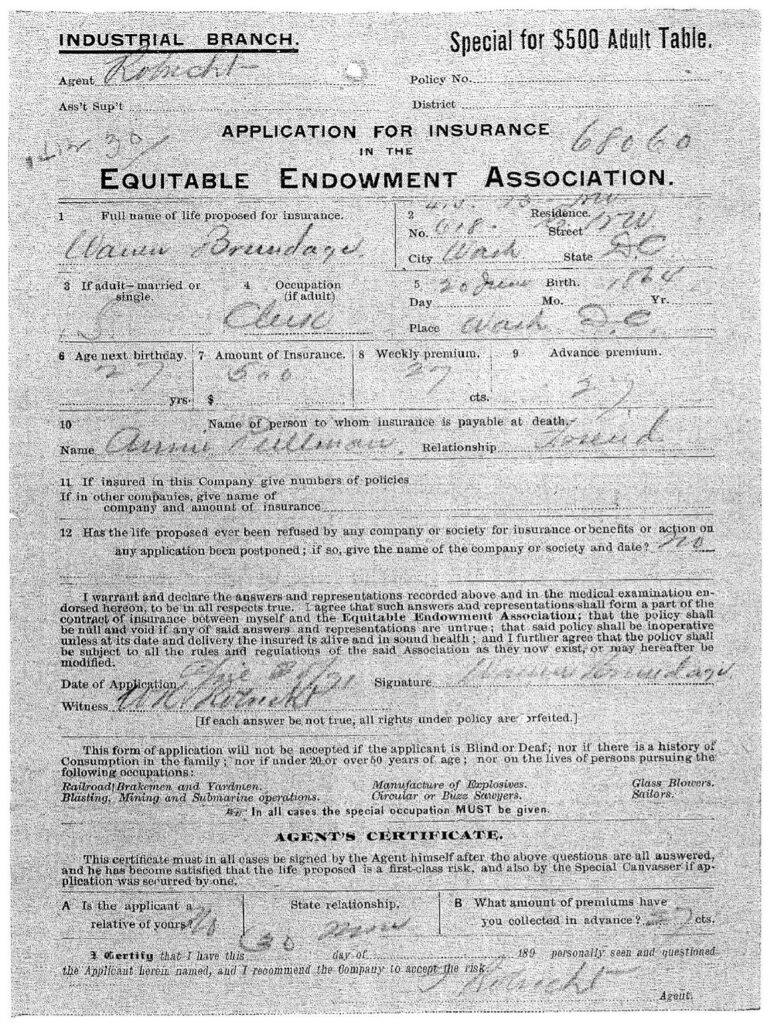

But shortly after his wedding night, Brundage began staying out until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. Rumors swirled. He was said to be frequenting a “house of ill fame,” infatuated with a “woman of the town” who called herself Pauline Gerard but whose real name was Annie Pullman. For a time, the gossip outran the evidence, and the church had no grounds to act. That is, until Brundage tried to take out a life insurance policy.

One day, Metropolitan’s deacons were approached by an insurance agent and a medical examiner—neither church members—who were aware of Brundage’s involvement in the church and concerned enough to come forward. They shared a copy of Brundage’s insurance application, which named Annie Pullman as his beneficiary. Even more damning, the address listed on the form was 404 13th St. NW, a known brothel.

That was all the deacons needed. On February 11, 1892, the church voted to exclude Brundage from membership “acting under the injunction given in the Scriptures, as found in Second Thessalonians, third chapter and sixth verse.”11 . “Now we command you, brothers, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from any brother who is walking in idleness and not in accord with the tradition that you received from us” (2 Thes. 3:6)

Case closed?

Not quite. Days before the vote, the church received a sharply worded letter from Brundage’s attorney warning that the church’s actions were unjust, unscriptural, and potentially actionable.

The threat of a lawsuit now loomed large. Would the church back down?

I discovered this story while digging through our church archives as part of research for my book on the history of Capitol Hill Baptist Church (A Light on the Hill, Crossway). In a file labeled “The Brundage Case,” I found over thirty pages of handwritten notes and letters—many from attorney F.J. Chapman—documenting the conflict from every angle.

Chapman had written to the deacons as early as June 1891, requesting any written charges and the names of accusers. When the case formally moved forward in early 1892, he fired off letters arguing that Brundage had been prejudged, that the process violated biblical standards, and that exclusion was not warranted. Brundage, he insisted, should have been “admonished, and more than once, if necessary,” citing passages like Galatians 6:1, James 5:20, and Titus 3:10.

After Brundage was excluded, Chapman escalated. In a March 1 letter, he accused the board of acting contrary to Scripture and claimed their actions were part of a broader pattern of prejudice and abuse. He even attempted to reinterpret 1 Corinthians 5, arguing that the church had misunderstood Paul’s teaching on how to treat the immoral brother.

The church replied on March 30. They acknowledged his letter. They disagreed with his interpretation. And they stood firm.

Brundage never sued. The legal threat fizzled. But the test was real—and churches today would do well to reflect on what happened.

What can we learn from the Brundage case? Here are three takeaways for churches considering church discipline today.

Don’t think about practicing church discipline if your church lacks a constitution or membership covenant. These documents aren’t bureaucratic red tape—they’re vital tools for faithfulness. They define what church membership means and what kind of accountability members agree to uphold. They therefore protect the church from legal challenges by defining the church’s practices and commitments.

When Metropolitan Baptist Church formed in 1878, their first acts were to adopt a church constitution and covenant. When the Brundage case surfaced, the church had clear processes in place. They weren’t scrambling to figure out what to do or what “discipline” meant. They simply acted in accordance with their established procedures.

Brundage’s attorney threatened legal action, but he had nothing to stand on. The church had followed its own rules. They documented the process. They offered Brundage a chance to defend himself. They even treated him with dignity, urging him to repent and return, rather than eagerly rushing to expel him.

Churches today should be wise and cautious, but not fearful. U.S. courts have consistently recognized a church’s First Amendment right to govern its internal affairs, especially when it comes to church membership and discipline. If your church acts consistently, clearly, and according to agreed-upon documents, you’re on firm legal ground.

The Brundage case wasn’t about shaming a sinner. It was about preserving the holiness of the church and protecting its witness to the gospel. The deacons weren’t out for blood. One even wrote that “the Board of Deacons would more gladly vote for his re-admission to membership than they would for his expulsion.”

Discipline, when done rightly, is a form of love. It upholds the seriousness of sin, but also opens the door to restoration. The goal is not mere exclusion—it’s repentance and reconciliation.

If we neglect discipline, we dilute our witness. We tell the world that sin isn’t serious and holiness isn’t worth preserving. But when we discipline rightly—with clarity, compassion, and courage—we demonstrate the holiness of Christ’s body on earth and the power of the gospel to transform lives.

Should the threat of lawsuits keep you from practicing church discipline? Not if you’re clear, careful, and grounded in Scripture. Not if your documents are in order and your motives are right. And certainly not if you fear God more than man. Churches should not be reckless. But neither should they be intimidated. God’s Word is clear. His church is called to be holy. And our witness depends on our willingness to practice what we preach.