Does the Book of Acts Teach Spontaneous Baptisms?

Spontaneous baptisms have been receiving a lot of attention of late. With the hashtags #BaptismSunday and #FilltheTank, Southern Baptist Convention leadership have been calling on SBC churches to participate in a nationwide push for baptisms this Easter Sunday, April 12.[1] They present it as an opportunity for unbelieving attendees and unbaptized believers to respond to the gospel by taking that “first step of obedience and faith” of baptism. Some of these baptisms will happen after several weeks of discipling and deciding; many of them will happen spontaneously.

Last year, for instance, one church practiced spontaneous baptisms on Easter Sunday and baptized 586 people.[2]

What should we make of this?

WHAT ARE SPONTANEOUS BAPTISMS?

First, a definition is in order. The Oxford Dictionary’s definition of “spontaneous” fits these baptisms well: an action “performed as a result of a sudden inner impulse or inclination and without premeditation or external stimulus.”[3]

A baptism is spontaneous in when it happens without forethought or planning. They’re spontaneous because some individuals didn’t go to church that morning planning to be baptized.

CHURCH HISTORY & PRE-MEDITATED BAPTISM

Historically, baptisms have been treated as planned rather than spontaneous events. The Didache (96 AD) instructs baptismal candidates to fast for one or two days leading up to the baptism (Didache, 7:4). In the fourth century, Cyril of Jerusalem required those seeking baptism and membership to complete forty lectures, a process described by one historian as “long and arduous.”[4] The same was true of Ambrose of Milan who only baptized Augustine after the customary season of “intense Lenten preparation and a course of postbaptismal instruction.”[5]

Why such delay? As Cyril of Jerusalem explained in his first catechetical lecture to baptismal candidates, being baptized multiple times is not an option. As such, it’s not a matter to take lightly:

This bath is not to be taken two or three times, else you might say, if I do not succeed at the first trial, I shall go right at the second. But in this matter, if you do not succeed this once, there is no correcting it. For there is “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” seeing that certain heretics repeat baptism, but only such, and of course what they did in the first instance was not baptism.[6]

That’s the witness of church history. But what about the New Testament? Here, disagreement emerges.

THE PATTERN OF ACTS

SBC president J.D. Greear argues that his convictions about baptism changed as a result of studying Acts: “Our church chose to hold our first [spontaneous] baptism service after we noticed the biblical pattern of spontaneous baptisms while preaching through a series in the book of Acts.”[7] He continues,

After all, every single baptism recorded in the New Testament, without exception, is spontaneous and immediate. For New Testament believers, the pattern was alarmingly simple: Believe, confess, get baptized. There was never a gap between when a person trusted Christ and when that person was baptized. Not one.[8]

This argument is powerful, and if true, would seem to tilt the table. He’s not alone in this. Many contemporary Baptist scholars agree with his assessment. Here’s how Bobby Jamieson addresses the question in Going Public:

Explicitly, in the rest of Acts, we read over and over again of people accepting the gospel and being immediately baptized. As the Ethiopian eunuch put it immediately after hearing the gospel from Philip, “See, here is water! What prevents me from being baptized?” (Acts 8:36; cf. 10:48; 16:15, 33; 19:5).[9]

Tom Schreiner also agrees. In the context of arguing against infant baptism, he affirms that,

In the NT era it was unheard of to separate baptism from faith in Christ for such a long period. Baptism occurred either immediately after or very soon after people believed. The short interval between faith and baptism is evident from numerous examples in the book of Acts (Acts 2:41; 8:12–13; 8:38; 9:18; 10:48; 16:15,33; 18:8; 19:5).[10]

Both Jamieson and Schreiner use the same word as Greear to describe the timing of baptisms in the Book of Acts: immediate. Assessing the data, this seems to be largely accurate.

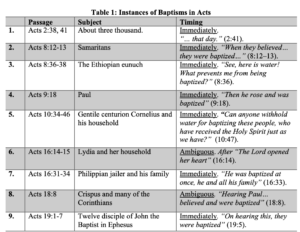

Of the nine instances of baptism in Acts, two are ambiguous about the timing: the baptism of Lydia and her household in Philippi in Acts 16:14–15, and the Corinthians who “believed and were baptized” in Acts 18:8. Two involve the delayed reception of the Holy Spirit until after baptism: the Samaritans in Acts 8, and the baptism of the twelve disciples of John the Baptist at Ephesus in Acts 19:5. We’re left with five instances of baptism as possible models for spontaneous baptisms. (For a comprehensive list of baptisms in Acts see Table 1 below.)

Here are the five spontaneous instances of baptism:

- Pentecost (Acts 2:38, 41)

- The Ethiopian Eunuch (Acts 8:36–38)

- Saul (Acts 9:18)

- Cornelius and his household (Acts 10:34–46)

- The Philippian jailer and his family (Acts 16:33)

THE PURPOSES OF BAPTISMS IN ACTS

The pattern of immediate baptisms is relatively clear. The question, however, is whether or not these examples of spontaneity are normative for churches today. Can we draw a positive warrant from them that spontaneous baptisms are permissible or even required?

Luke records surprisingly few baptisms in Acts. In a book where thousands are converted and dozens of churches are started, he mentions only nine instances of baptism. In fact, Paul’s entire first missionary journey goes by without a single mention of baptism (see Acts 13–14). This suggests that the baptisms actually recorded are unusual or even inimitable. It raises the question: what’s so special about the recorded baptisms in Acts?

Three features characterize the baptisms in Acts:

- The baptisms recorded all involve “first converts” in a historically-redemptively significant setting.

- Nearly every baptism is accompanied by supernatural acts of the Holy Spirit.

- Each baptism takes place in response to believing the Apostolic message.

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

THE BAPTISM OF “FIRST CONVERTS”

The dominant theme of the baptisms in Acts is that they all involve so-called “first converts”—that is, the first people to believe in new regions that follow the outward trajectory of Jesus’ commission: “you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). So on Pentecost, 3000 are baptized as the church is established in Jerusalem. Just as the Exodus marked the creation of the people of God in the Old Testament and was accompanied by supernatural signs of judgment, so the New Covenant people of God is created at Pentecost with similar signs and wonders.

In Acts 8, the gospel comes to the historic enemies of the Jews—the Samaritans—and they are baptized (Acts 8:12–13). Later in the same chapter, the gospel reaches an Ethiopian proselyte (Acts 8:36–38). Continuing the theme of gospel expansion, Acts 10 records the first instance of Gentile conversions and baptisms (Acts 10:34–46).

At this point, however, the baptisms in Acts basically stop. With the notable exceptions of the baptisms in Philippi (Acts 16:14–15; 16:31–34) and Corinth, which signal the move outward to the ends of the earth, Luke largely goes silent. Why? Because one of the main reasons baptisms are recorded in Acts is to highlight God’s work in pioneer settings as the gospel advances to new regions.

SUPERNATURAL ACTS OF THE HOLY SPIRIT

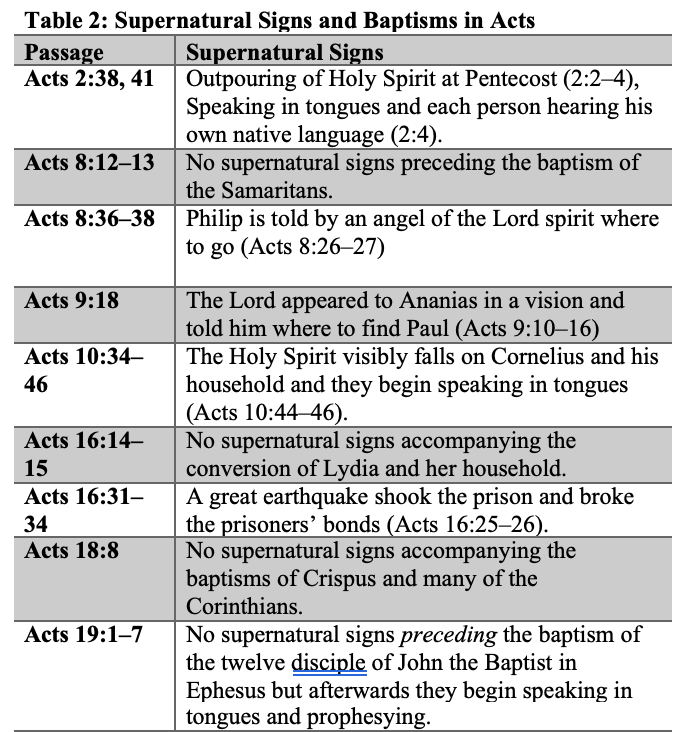

Another dominant theme of baptisms in Acts is the visible and evident work of the Holy Spirit. Nearly every baptism is accompanied by clear supernatural signs (for a comprehensive list, see Table 2 below).

At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descended visibly on the disciples in flames of fire and with the sound of a loud wind (2:2–4). Furthermore, they spoke in tongues, and each person in Jerusalem heard the Word of God in their own language (2:4). In Acts 8, Philip is directed by the Holy Spirit and told exactly where to go (Acts 8:26–27). In Acts 9, the Lord appears to Ananias in a vision and tells him where to find Paul (Acts 9:10–16). In Acts 10:34–46, the Holy Spirit falls visibly on the Cornelius and his household; they begin speaking in tongues (Acts 10:44–46). In Philippi in Acts 16, a great earthquake shakes the prison and broke each prisoner’s bonds (Acts 16:25–26).

What’s the purpose of connecting baptism with the visible work of the Holy Spirit? Luke is highlighting that the Spirit of God is driving the expansion of the gospel and the growth of the church. As the church grows and expands beyond Jerusalem, these visible manifestations of the church help its unity because they signify the movement of the same Spirit. As Paul writes to the Ephesians, “There is one body and one Spirit—just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call—one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Ephesians 4:4–5). The unity of the church is not undermined by gospel expansion because the Holy Spirit is fulfilling Jesus’ prayer that “they may be one” (John 17:11b. See also 17:21, 23).

FAITH IN THE APOSTOLIC MESSAGE

The third theme accompanying the baptisms of Acts is their connection to the preaching of the apostolic message, the gospel. Throughout Acts, it’s clear: true faith comes in response to the preaching of the gospel through the power of the Holy Spirit. This is evident at Pentecost where those baptized are all who “received his word” (Acts 2:38). Likewise, the Samaritans were baptized “when they believed” (Acts 8:12). As a result, we should not be surprised that the agents of baptism in Acts are either the apostles themselves (Philip, Peter, Paul) or those closely associated with them (Ananias).

So, it seems clear that the baptisms in Acts demonstrate the unity of the church in the power of the Holy Spirit, built on the foundation of the apostolic message. Generally speaking, these baptisms, like the book as a whole, follow the steps outlined in Acts 1:8: “And you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” The point of each recorded baptism is to highlight how the expansion of the gospel doesn’t result in the fragmentation of the church. Rather, the church remains firmly united despite their diversity because of the Holy Spirit and the consistent apostolic message.

WHAT ABOUT THOSE WHO RECEIVE THE HOLY SPIRIT AFTER BAPTISM?

These criteria also make sense of the “anomalies” in Acts. Namely, the Samaritans in Acts 8 and the disciples of John in Acts 19 who are baptized but do not receive the Holy Spirit until an apostle lays hands on them (8:16; 19:6). Why the delay?

The historic animosity between Jews and Samaritans could have lead to separate churches. Without Peter—acting as a representative of the apostles—witnessing the genuineness of the Samaritans’ faith, the Jerusalem church may have never welcomed the Samaritans as equal members of the Kingdom of God (Galatians 3:28). On the other hand, the Samaritans may have resisted the Jewish apostles’ authority apart from witnessing that Peter was the conduit through which the Holy Spirit was given to them. So the pattern remains intact: baptisms in Acts demonstrate the unity of the church in the Holy Spirit built on the apostolic message as the church expands.

Something similar is going on in Acts 19:1–7 where Paul happens upon a group John the Baptist’s disciples in Ephesus. They’d received John’s baptism of repentance, but not the Holy Spirit. Paul then baptized them in the “name of the Lord Jesus,” and when he lays hands on them they received the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues and prophesying (Acts 19:1–7).

These disciples of John the Baptist are a “transitional” group. Like the Samaritans, there was the risk of a fragmented church, one separated from the apostolic message. As such, it was important for them to see that Paul is the conduit through which they received the Holy Spirit. As Peterson writes, “In salvation-historical terms, they were a transitional group, whose full incorporation into the church needed to be openly demonstrated.”[11]

With these two exceptions in mind, a definite pattern emerges regarding baptism in Acts: those who respond in faith to the preaching of the apostolic message show supernatural evidence of the Holy Spirit and should be baptized. That is the pattern of baptisms in Acts.

PHILIPPI & CORINTH: CASE STUDIES IN BAPTISM & TIMING

We can now make sense of another curious phenomenon. None of the baptisms in Acts can be properly described as “ordinary.” As has been said, each of them reflects “first-convert” baptisms, generally in completely unreached areas where there is no established church. An additional unusual feature is the prominent role given to the accompanying signs of the Holy Spirit (see Table 2 above).

But let’s set aside the Samaritans (Acts 8) and the disciples of John (Acts 19:1–7) for a moment. Two baptisms leave out any mention of visible supernatural work: the baptism of Lydia and her household at Philippi (Acts 16:14–15), and the baptism of the Corinthians who “believed and were baptized” (Acts 18:8).

Here’s where it gets interesting: it just so happens that these two baptisms also leave out any mention of the timing of baptism. In the case of Lydia, Acts 16:14 simply says, “The Lord opened her heart to what was said by Paul. And after she was baptized, and her household as well, she urged us, saying, ‘If you have judged me to be faithful to the Lord, come to my house and stay.” And she prevailed upon us” (16:14–15). Likewise, Acts 18 simply records that “many of the Corinthians hearing Paul believed and were baptized” (Acts 18:8).

Now, it’s possible to read this as taking place immediately. In all likelihood, however, the preaching of the gospel not only to Lydia but also to her household would have taken some time. Commenting on the timing of Lydia’s baptism, Peterson says, “Some period of instruction involving her household presumably took place before she and the members of her household were baptized.”[12] Schnabel agrees with this assessment, observing that the imperfect tense in 16:13 for “spoke” (elaloumen) may indicate “teaching over an extended period of time.”[13]

Luke has already demonstrated a tendency to comment on timing with phrases such as “that day” (Acts 2:41), “at once” (16:33), and “on hearing this” (Acts 19:5). But in these two cases, he omits any references to time whatsoever.

We find something similar in the other “ordinary” baptism in Acts 18. One man in particular is singled out: Crispus, the ruler of the synagogue. After a period of time, he and his household “believed in the Lord,” and seemingly together with many of the Corinthians were baptized (Acts 18:8). We know from 1 Corinthians 1:14–16 that Crispus was one of the few converts baptized by Paul. In addition, 1 Corinthians 16:15 adds that he was one of the first converts in Achaia. In Acts 18, Luke simply records that at some point he and his household came to believe in the Lord. We’re not told about the other Corinthians who were baptized, but Peterson suggests that the use of the continuous tenses in the Greek (“hearing” and “believing” and “being baptized”) suggests an ongoing pattern of responding to gospel preaching.[14]

If someone is looking for baptism precedents in Acts that apply to today, then it seems to me that Lydia and Corinth offer the clearest examples. It’s true: both Lydia and her household and Crispus and his Corinthian counterparts double as “first-convert” baptisms in regions before a church has been established. In that sense, they’re appropriate models for pioneer missionaries. But they’re also the most “normal” insofar as they don’t accompany miraculous signs of the Holy Spirit (see Table 2).

However, even in these relatively “normal” instances of baptism, Luke makes no mention of timing. He’s uncharacteristically silent, perhaps suggesting a longer process of instruction and assessment. These converts are baptized as the Word is taught and the Holy Spirit opens hearts.

It’s unfortunate for proponents of “spontaneous baptisms” that the only two examples from the Acts that serve as likely models because of their omission of evident supernatural signs are also the two instances where timing is omitted altogether.

SHOULD WE PRACTICE SPONTANEOUS BAPTISMS?

The claim that Acts demonstrates a uniform pattern of spontaneous baptisms is overstated. One friend has said, “Every single baptism recorded in the New Testament, without exception, is spontaneous and immediate. . . . There was never a gap between when a person trusted Christ and when that person was baptized. Not one.”[15] We have seen that the data is more complex than this statement suggests. First of all, it has been demonstrated that Luke’s purpose in recording baptisms in Acts was not simply to provide a model to follow. In this, we would do well to heed the words of Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart:

Luke’s interest does not seem to be on standardizing things, bringing everything into uniformity. When he records individual conversions, there are usually two elements included: water baptism and the gift of the Spirit. But these can be in reverse order, with or without the laying on of hands, with or without the mention of tongues, and scarcely ever with a specific mention of repentance, even after what Peter says in 2:38–39. . . . Such diversity probably means that no specific example is being set forth as the model Christian experience.[16]

Indeed, to claim from Acts a precedent for spontaneous baptisms is to misunderstand the purpose of the baptisms as recorded: not as models of normal practices but as redemptive-historical Ebenezers of the progress of the gospel and the unity of the church.

It would be more accurate to state that seven of the nine baptisms in Acts seem to occur immediately, but in all of these seven instances supernatural signs are evident. However, two of the instances—Lydia and her household in Acts 16:14–15 and Crispus and the Corinthians in Acts 18:8—do not specify a time. These two unspecified baptisms don’t mention the timing of baptism, yet they’re the closest we get to “normal” baptisms in Acts.

HERMENEUTICS 101

Even if Acts set forth a uniform pattern of spontaneous baptisms, such a pattern wouldn’t necessarily warrant the practice of spontaneous baptisms in our churches today. One of the first lessons of hermeneutics is that descriptive does not necessarily mean prescriptive. A few examples from the first chapters of Acts illustrate this fact:[17]

- Matthias is chosen to fill the position of Apostle by drawing lots (Acts 1:26). Is that how leaders should be chosen in our churches?

- Tongues of fire fall on the heads of the believers at Pentecost as they are filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:1–4). Should we expect to see tongues of fire accompany the work of the Holy Spirit today?

- Peter and John heal a crippled man at the temple gate by commanding him to walk in the name of Jesus (Acts 3:6). Should we regularly instruct disabled people to do the humanly impossible in the name of Jesus?

These examples illustrate the point. The mere presence of a pattern is insufficient warrant for adopting a practice in our churches today. And this problem is not hypothetical. Roman Catholics argue that Judas’ replacement shows that the chair of bishops continues, and if Judas’s chair was filled, surely Peter’s was as well. And so the pope holds the chair of Peter.

Instead, we should apply two principles for discerning whether or not a pattern is binding. Here, I’m drawing from Stephen Voorwinde’s article “How Normative Is Acts?”[18] First, we should assume the principle of non-contradiction: however complex the issue, we should assume the unity of Scripture and draw widely from Scripture to discern which principles are binding. Second, we should look for reinforcement for the doctrine or practice in question in other parts of the New Testament. As John Stott puts it, “What is descriptive is valuable only in so far as it is interpreted by what is didactic.” [19]

Applying these two principles to the issue of the timing of baptism we find the rest of the New Testament strangely silent. Nowhere besides Acts is the timing of baptism described. Thus, the examples in Acts, however many and however uniform, do not constitute a positive warrant for baptizing immediately.

THE NATURE OF BAPTISM REQUIRES A POSTURE OF CAUTION

Instead, the uniform pattern—not only in Acts, but throughout the whole New Testament—is that the proper subject of baptism is always a believer. In fact, baptism is so closely connected with conversion that Paul can speak of them as one and the same event:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life (Romans 6:4–5).

Or consider how Paul writes in Galatians: “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ” (Galatians 3:27). Paul’s assumption here is that everyone who has been baptized is in Christ.

This New Testament doctrine of the nature of baptism requires a posture of caution. This has been the historic Baptist position for centuries. As J. D. Greear has written, “Baptism is postconversion because it symbolizes a public choice to follow Jesus. Thus, to knowingly baptize people who aren’t saved yet would pervert and undermine the symbol and its role in the church.”[20]

Mark Dever advises as much when he writes that “the person desiring baptism should be forbidden it until repentance for sin is evidenced.”[21] In other words, there should be a period of observation sufficient for positive warrant of the genuineness of someone’s faith and repentance before they can be admitted to the ordinance of baptism and membership of a church. This raises yet another question: do these spontaneous baptisms usher men and women into church membership?

Dever acknowledges that “no delay is present in baptism accounts in Acts, but in Acts there would have been little question of the state of those people.” This is due to the readiness of Jews to receive the gospel message, and the very high social cost of identifying with Christ in baptism due to persecution. Thus, while “the Bible gives us no command for immediacy or for delay,” Dever writes, “the nature of baptism clearly shows that it is to be only for those who profess saving faith. Therefore, if delay is necessary to ascertain genuine saving faith in the person, then delay would seem to be the path of prudence.”[22] “Delaying” baptism is not only warranted but necessary when the genuineness of someone’s faith or the validity of their repentance is difficult to discern.

CONCLUSION

Upon closer examination, the baptisms in Acts don’t fit neatly into a pattern of spontaneous baptisms. Rather, nearly every baptism in Acts fits into a pattern of critical salvation-historical moments as the young church expands geographically. Luke’s burden is to highlight the unity of the church around the apostolic faith as the church crosses boundaries and expands to new territories. The salvation-historical uniqueness of these baptism events in Acts is shown in part by accompanying supernatural signs.

The exception to this pattern are the two “normal” baptisms of Lydia and her household in Acts 16:14–15 and Crispus and the Corinthians in Acts 18:8. In both of these instances, however, the timing of baptism is not specified, thus undercutting the argument for spontaneous baptisms. These two instances better serve as illustrations of baptisms in pioneer church planting settings without an established church.

Our context today is simply not analogous. Instead, the nature of baptism requires a posture of caution. As churches weigh the two competing priorities of baptizing all believers without carelessly baptizing unbelievers, a posture of caution is warranted.

Sadly, too many churches are marked by a pattern of carelessness in handling membership and baptism. Rather than loosening our practices, wisdom requires a greater degree of thoughtfulness and carefulness. In his book The Soul-Winner, Charles Spurgeon puts it well,

Do your work steadily and well, so that those who come after you may not have to say that it was far more trouble to them to clear the church of those who ought never to have been admitted than it was to you to admit them.[23]

May that be true of our churches, and may God give us wisdom as we consider what method of taking in members is best suited to protect the gospel and the integrity of our churches—both now and in the generations to come.

* * * * *

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Send Network, “Greear urges churches to ‘Fill the Tank’ on Easter.” https://www.namb.net/send-network-blog/greear-urges-churches-to-fill-the-tank-on-easter/. Accessed on February 14, 2020.

[2] Diana Chandler, “586 baptisms one Sunday at McLean Bible Church.” http://www.bpnews.net/53495/586-baptisms-one-sunday-at-mclean-bible-church. Accessed on February 14, 2020.

[3] Oxford English Dictionary. See entry under “spontaneous.”

[4] Cyril of Jerusalem and Nemesius of Emesa, Ed. Telfer William. Vol. IV of the Library of Christian Classics (Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1955), 30.

[5] Gary Wills, Font of Life: Ambrose, Augustine, and the Mystery of Baptism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 86.

[6] Cyril of Jerusalem, The Catechetical Lectures, “Procatechesis” 7.

[7] J.D. Greear, “J.D. GREEAR: Why Baptism Sunday?” http://www.bpnews.net/53426/jd-greear-why-baptism-sunday. Accessed on February 14, 2020.

[8] J.D. Greear, “J.D. GREEAR: Why Baptism Sunday?” http://www.bpnews.net/53426/jd-greear-why-baptism-sunday. Accessed on February 14, 2020.

[9] Bobby Jamieson, “Going Public,” 38. Italics mine.

[10] Tom Schreiner, Believer’s Baptism, 93. Italics mine.

[11] Peterson, Acts, 533.

[12] Peterson, Acts, 460.

[13] Schnabel, Acts, 680.

[14] Peterson, 512.

[15] J.D. Greear, “J.D. GREEAR: Why Baptism Sunday?” http://www.bpnews.net/53426/jd-greear-why-baptism-sunday. Accessed on February 14, 2020.

[16] Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth: A Guide to Understanding the Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982), 92. Italics mine.

[17] These examples are drawn from Stephen Voorwinde’s article “How Normative Is Acts?” https://www.rtc.edu.au/RTC/media/Documents/Vox%20articles/How-Normative-is-Acts.pdf?ext=.pdf. Accessed on February 14, 2020. Voorwinde lists 36 examples of such issues in the Book of Acts!

[18] https://www.rtc.edu.au/RTC/media/Documents/Vox%20articles/How-Normative-is-Acts.pdf?ext=.pdf. Accessed on February 14, 2020

[19] John R. W. Stott, Baptism and Fullness: The Work of the Holy Spirit Today (2nd ed.; Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1975), 15.

[20] J. D. Greear, Stop Asking Jesus Into Your Heart: How to Know for Sure You Are Saved, 114.

[21] Mark Dever, Believer’s Baptism, 336.

[22] Mark Dever, Believer’s Baptism, 345.

[23] Charles Spurgeon, The Soul-Winner, 25.