Relating Moses’s Law to Christians

When the New Testament speaks of God’s “law,” it almost always refers to Moses’s law or law-covenant.[1] This law is one expression of God’s eternal law, which grows out of his unchanging, righteous character. The eternal law manifests itself in different institutional and covenantal forms through the timeline of redemptive history. Indeed, those institutional and covenantal changes mark off one era of redemptive history from another. For example, God’s command for the first couple not to eat from the tree of knowledge pertaining to good and evil reveals the outworking of his eternal law at that moment, but it doesn’t directly bind us today. We, thus, can’t just say, “God’s law is eternal, so let’s apply that Garden command directly to us.” Rather, we need to do the tough work of figuring out how or in what sense such a law would apply.

The same principle applies to the Mosaic law, which clarified the way in which God’s eternal law was to govern ancient Israel at that particular time in history. The law through Moses was distinctive from anything that governed previous generations, and God gave it to ancient Israel and not to every nation on earth. For Christians today, the question then becomes: How does Moses’s law apply to believers today when so much has changed with Christ’s coming, not least of which is that we are part of the new covenant and not the old? With a simple alliteration, Brian Rosner has captured three principles that clarify the Christian’s relationship to the Mosaic law: repudiate, replace, and reappropriate.[2]

1. Biblical Authors Repudiate the Mosaic Law-Covenant.

Through his written code, Yahweh called Israel to holiness (Lev. 20:26; cf. 19:2; 20:7; 21:8). But Israel was stubborn, rebellious, and unbelieving (Deut. 9:6–7, 23–24; 29:4), which would ultimately result in the old covenant’s destructive end (31:16–18, 27–29). Paul, therefore, noted that the Mosaic law-covenant bore a ministry of “death” and “condemnation” (2 Cor. 3:7, 9; cf. Rom. 7:10). While “the law is holy” (Rom. 7:12; cf. 2:20), “the law is not of faith” (Gal. 3:12), meaning that the age of the Mosaic administration was characterized not by faith but unbelief.[3] By God’s purposes, the Mosaic law multiplied transgression (Rom. 5:20; Gal. 3:19), exposed sin (Rom. 3:20), and brought wrath (4:15) to show that “one is justified by faith apart from works of the law” (3:28; cf. Gal. 3:10; Jas. 2:10).

Christians repudiate the Mosaic law-covenant. As the author of Hebrews declared: “In speaking of a new covenant, he makes the first one obsolete” (Heb. 8:13). “The law made nothing perfect” (7:19), but in Christ, we find a “better hope” (7:19), a “better covenant” (7:22; cf. 8:6), “better promises” (8:6), “better sacrifices” (9:23), “better possession” (10:34), a “better country” (11:16), a “better life” (11:35), and a “better word” (12:24).

2. Biblical Authors Replace Moses’s Law with the New Covenant Law of Christ.

The grace and truth Jesus Christ brings supersedes the grace God bestowed through the Mosaic law (John 1:16–17). Christ has broken the condemning and controlling power of the law, such that Paul can say of believers, “You are not under law but under grace” (Rom. 6:14).

Moses knew that Israel’s system of worship was merely symbolic, which suggests that it would become obsolete when shadow moved to substance (Exod. 25:9, 40; Zech. 3:8–9; 6:12–13). In Christ, the substance has come (Col. 2:16–17; Heb. 9:11–12). Furthermore, Moses affirmed the need for a better covenant––one in which Yahweh would accomplish for Israel something better than the Mosaic covenant era. The law could not give life (Gal. 3:21), weakened as it was by the flesh (Rom. 8:3).

Moses anticipated a day when God’s people would listen to the voice of the new prophetic covenant mediator (Deut. 18:15) and God would cause his people to love him with their all (30:6, 8). The prophets equally longed for the day when God would teach every member of the multi-ethnic, blood-bought community (Isa. 54:13), when he would write his law on their hearts (Jer. 31:33) and cause them to walk in his statutes (Ezek. 36:27). These hopes are all realized today through the church (John 6:44–45; Rom. 2:14–15, 25–29; Phil. 3:3).

As Christians, our “release from the law” (Rom. 7:6), in part, means that the Mosaic law is no longer the judge of God’s people’s conduct.[4] The age of the Mosaic law-covenant has come to an end in Christ, so the law itself has ceased from having a determinative role (2 Cor. 3:4–18; Gal. 3:15–4:7).[5] As a written legal code, not one of the 613 stipulations in the Mosaic law-covenant directly binds Christians (cf. Acts 15:10; Gal. 4:5; 5:1–12; Eph. 2:14–16). Instead, Christians are bound by the law of Christ (1 Cor. 9:20–21; Gal. 6:2), which is summarized in the call to love our neighbor (Jas. 1:25; 2:8, 12).

Today, the guiding authority for Christians are Christ’s words brought through his apostles (i.e., the New Testament). Fulfilling Moses’s prediction of a prophetic covenant mediator, God declared of Jesus in Moses’s sight, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well-pleased; listen to Him!” (Matt. 17:5; cf. Deut. 18:15). Everyone who hears Christ’s words and acts on them is wise (Matt. 7:24–27), and the call to make disciples includes teaching others to obey Christ’s teaching (28:19–20). His instructions through his apostles now provide the essence for all Christian instruction (John 16:12–14; 17:8, 18, 20; 2 Thes. 2:15). The early church “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching” (Acts 2:42), for the church is “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone” (Eph. 2:20). Christians are part of the new covenant, not the old, and so they are bound to Christ’s law, not Moses’s law.

3. Biblical Authors Reappropriate Moses’s Law through Christ.

While Moses’s law doesn’t legally bind Christians, it remains indirectly authoritative, profitable, and instructive for believers through Christ’s mediation (cf. Rom. 4:23; 13:9; 15:4; 1 Cor. 10:11; 2 Tim. 3:16–17). Because Jesus fulfills various laws in different ways, we must consider each law in view of Christ’s work. While the New Testament only addresses a small number of Old Testament laws, its examples guide our handling of other related commands or prohibitions and illuminate each law’s lasting significance.

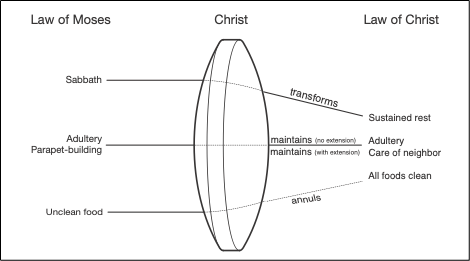

To illustrate Moses’s law’s lasting significance, consider Jesus as the lens through which the law must be interpreted (fig. 1). Some laws are unchanged before and after Christ, whereas others hit the lens and get “bent” in various ways. We find that Jesus’s coming maintains (with and without extension), transforms, and annuls various laws. Let’s consider these categories briefly.

- Maintains (no extension): When fulfilling Moses’s prohibitions against murder, adultery, theft, coveting, and the like (e.g., Exod. 20:13–17), Christ maintains the law’s essence without any extension from the old to new covenants (Matt. 15:18; 19:17–21; cf. Rom. 13:9). Obeying such laws would have looked the same in both eras.

- Maintains (with extension): When fulfilling Moses’s charge not to muzzle an ox while it is threshing (Deut. 25:4), Christ’s work extends the principle’s application to include paying wages to ministers (1 Cor. 9:8–12; 1 Tim. 5:17–18; cf. Matt. 10:10). Such extensions often occur in laws where their instruction includes cultural details that are different from our own; in such instances, we heed Jesus’s words at the end of the parable of the good Samaritan and “do likewise” (Luke 10:37), though working out the principle in a new way.

- Transforms: When fulfilling laws like Yahweh’s charge to observe the Sabbath (e.g., Deut. 5:12–15) or Moses’s directions on capital punishment (e.g., Deut. 22:22), Christ transforms. On the one hand, he secures sustained rest for his followers and calls them to receive it (Matt. 11:28–12:8), and on the other hand, his work leads to applying the charge to “purge the evil from your midst” to excommunication within the church (1 Cor. 5:13).

- Annuls: When fulfilling Moses’s laws about unclean food (e.g., Lev. 20:25–26), Christ annuls them, declaring all foods clean (Mark 7:19; cf. Acts 10:14–15; Rom. 14:20). But though he rescinded the diet restrictions, we still benefit from the commands by considering what they tell us about God and how they magnify Jesus’s work.

Figure 1. The Law’s Fulfillment through the Lens of Christ[6]

CONCLUSION

When viewing the Old Testament through the lens of Christ, everything operates as Christian Scripture written “for our instruction” (Rom. 15:4; cf. 4:23; 1 Cor. 10:11). We access and apply Moses’s law only through Christ and in view of the apostles’ teaching, which together ground and sustain the church (Acts 2:42; Eph. 2:20; cf. Matt. 7:24–27; 17:5; 28:20; John 16:12–14; 17:8, 18, 20; 2 Thes. 2:15; Heb. 1:1–2).[7]

* * * * *

[1] This article abridges material taken from chapter 10 of Jason S. DeRouchie’s forthcoming Delighting in the Old Testament: Through Christ and for Christ (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2024). Used with permission.

[2] Brian S. Rosner, Paul and the Law: Keeping the Commandments of God, NSBT 31 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2013), 208–209, 217–22.

[3] Jason S. DeRouchie, “Question 34: How Does Galatians 3:12 Use Leviticus 18:5?,” in 40 Questions about Biblical Theology, by Jason S. DeRouchie, Oren R. Martin, and Andrew David Naselli, 40 Questions (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2020), 327–37; Jason S. DeRouchie, “The Use of Leviticus 18:5 in Galatians 3:12: A Redemptive-Historical Reassessment,” Them 45.2 (2020): 240–59.

[4] So also Douglas J. Moo, “The Law of Christ as the Fulfillment of the Law of Moses: A Modified Lutheran View,” in Five Views on Law and Gospel, ed. Wayne G. Strickland, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 343; cf. 375.

[5] Moo, “Law of Christ,” 359.

[6] I thank my student Benjamin Holvey who initially inspired this lens illustration.

[7] For more on this redemptive-historical approach to a Christian’s relationship to Old Testament law, see David A. Dorsey, “The Law of Moses and the Christian: A Compromise,” JETS 34 (1991): 321–34; Vern S. Poythress, The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1991), 251–86; Moo, “Law of Christ,” 317–76; Tom Wells and Fred G. Zaspel, New Covenant Theology: Description, Definition, Defense (Frederick, MD: New Covenant Media), 77–160, esp. 126–27, 157–60; Daniel M. Doriani, “A Redemptive-Historical Model,” in Four Views on Moving beyond the Bible to Theology, ed. Gary T. Meadors, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), 51–56, 75–121, 205–9, 255–61; Jason C. Meyer, The End of the Law: Mosaic Covenant in Pauline Theology, NAC Studies in Bible and Theology 7 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2009); Jason C. Meyer, “The Mosaic Law, Theological Systems, and the Glory of Christ,” in Progressive Covenantalism: Charting a Course between Dispensational and Covenant Theologies, ed. Stephen J. Wellum and Brent E. Parker (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2016), 66–99; Thomas R. Schreiner, 40 Questions about Christians and Biblical Law, 40 Questions (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2010); Rosner, Paul and the Law; William W. Combs, “Paul, the Law, and Dispensationalism,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 18 (2013): 19–39; Stephen J. Wellum, “Progressive Covenantalism and the Doing of Ethics,” in Progressive Covenantalism: Charting a Course between Dispensational and Covenant Theologies, ed. Stephen J. Wellum and Brent E. Parker (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2016), 215–33.