Revival Comes to Washington: An Analysis of the 1876 Revival in the Nation’s Capital

Synopsis: In 1876, Washington churches partnered together to host a 105-day-long revival meeting in the National Capital. This event illustrates the extent to which modern revivalism impacted American evangelicalism and provides a broader backdrop for many of the revivalistic methods we continue to see practiced today.

In the nineteenth century, revivals ceased to be regarded as the spontaneous work of the Holy Spirit and instead became planned events: the result of intercessory prayer, careful planning, and meticulous execution. As Iain Murray notes with irony, “Instead of being ‘surprising’ [revivals] might now be even announced in advance.”[1]The difference between the older reliance on the ordinary means of grace and the newer reliance on ever-changing methods has been aptly described as the difference between “revival and revivalism.”[2]

This article examines one instance of “revivalism” in 1876—when the churches of Washington, D.C. partnered together to bring a world-famous revivalist to the National Capital for a hundred-day-long series of protracted meetings. I will examine four features of this Washington revival—partnership, prayer, press, and preaching—before offering three concluding reflections that attempt to bridge the gap between past practices and present realities.

It would be simplistic to label this event either “good” or “bad.” Like all imperfect efforts, the good and bad are mixed. Instead of rendering a conclusive verdict, this article simply records, analyzes, and observes how much of the present obsession with numbers, decisions, and new methods finds its roots in nineteenth-century revivalism.

PARTNERSHIP

Between 1875 and 1876, five Washington pastors came together to pray for revival.[3] They represented the various Protestant denominations of the city: Congregational, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, and Lutheran. Together, they formed the “Union Revival Committee” in order to organize a revival in the Capital.[4] They secured the services of Edward Payson Hammond and his accompanying musician William W. Bentley of New York, who agreed to spend the spring of 1876 in Washington.[5]

Figure 2: A sketch of Edward Payson Hammond from his biography ‘The Reaper and the Harvest’ [6]

PRAYER

As the churches awaited Hammond’s arrival, they began to gather daily for prayer. At these midday prayer meetings—similar to the famous New York prayer revival—attendees were encouraged to write down or publicly share prayer requests. Each prayer request was read aloud and recorded simply: “a father for his two sons,” “for a man and wife who have not been to church for nine years,” “for a backslider who is not satisfied,” “for a man who wants to be a Christian, but his wife is his hindrance,” “for an unconverted mother and father,” etc.[7] These daily prayer meetings, which had begun long before Hammond’s arrival and continued long after his departure, constituted the core of the revival in Washington.

PRESS

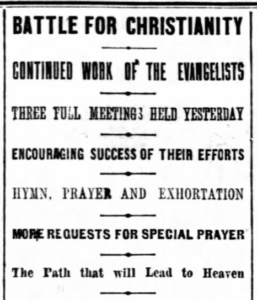

Like other revivalists, Hammond depended heavily on friendly press.[8] While he “could only speak to hundreds, the secular papers could speak to thousands.”[9] Moreover, like a self-fulfilling prophecy, the more the Press touted the revival’s success, the greater the crowds that would be drawn out of curiosity. As his biographer explained, “The best way to promote revivals of religion is to tell of them in other places.”[10]

As a result, Hammond kept meticulous records so as to always be ready to cite his successes to the press. One of his innovations was to ask every person who came forward to the inquiry meeting to sign a “covenant card,” which stated, “I, the undersigned, hope I have found Jesus to be my precious Savior; and I promise, with his help, to live as his loving child and faithful servant all my life.” While this card was kept by the signer, their name was recorded in Hammond’s book to keep track of the number of converts.[11]

Figure 3: National Republican, 19 Feb 1876, page 4

PREACHING

The revival meetings formally commenced on Saturday, February 5, 1876, at St. Paul’s English Lutheran Church in Washington, DC.[12] The locations for the meetings shifted as various churches made their buildings available. Two to three meetings were held daily, each consisting of Bible reading, exposition, prayer, and testimony. During the main meetings in the evening, Hammond would preach an evangelistic sermon, which included a gospel presentation and a call to response.[13]

But Hammond’s gospel presentation often contained strong notes of moral reform and self-improvement. For instance, in his message on Sunday April 2, 1876, to an overflowing crowd at First Congregational Church, Hammond chose Amos 6:1 for his text, “Woe to those who are at ease in Zion.” His message focused largely on the moral plight of society and the need for personal transformation. “If you go through the saloons and hotels and offices of this city and listen to men who are not Christians talking,” he decried, “you will hear God’s moral law being attacked, and his infinite power and wisdom called into question. And yet, you say, this is none of our business.” At the conclusion, “the different classes present were invited to rise for prayers,” and “nearly all arose by an involuntary impulse.”[14]

By decrying public and private wickedness and identifying Christ as the only solution, Hammond risked falling into preaching a message of moral transformation. While he presented Christ as the only way to personal salvation, the balance of Hammond’s preaching focused on broad social reform: society was falling apart and only personal salvation could ensure the morality needed to prevent further decay.[15]

ASSESSING THE FRUIT

Approximately 285 official revival meetings were held in Washington, D.C. between February 5, 1876, and May 20, 1876—a span of 105 days. Ever the prodigious record-keeper, Hammond claimed to have converted 1,900 in Washington,[16]the majority of which were children under sixteen.[17] If this number is accurate, and Washington’s population was around 150,000 in 1876,[18] then somewhere around 1 in 78, or 1.3 percent of Washington’s residents were claimed by Hammond as “converts” during his revival.

But long after Hammond had moved on to the next city, Washington pastors and churches dealt with the fallout and consequences of the revival. What implications did revivalism have on pastoral ministry in the nation’s capital?

1. Pressure to adopt new methods

The “new measures” of revivalism created distinct pressures for pastors to follow suit or fall behind. If a church refused to participate in the revival, they were unlikely to reap any of its “fruits.” Revivals presented an opportunity to hear new preachers, attend new churches, and frequently led to changes in membership from one denomination or church to another.

Of course, not all of Washington churches participated. And those who failed to play along lost the most. Pastors felt a new pressure to grow the church through revivals or risk falling behind. In the long run, this undermined the slow, patient work of pastoring.

2. Dependence on new measures for church growth

A second consequence of the growing revivalism was a reliance on new methods for bringing in new members. Rather than spontaneous professions of faith over the course of the year, revival services were increasingly seen as the proper place for professions of faith. For example, between 1884 and 1888, 91 percent of all professions of faith at Metropolitan Baptist Church occurred during protracted meetings. If a pastor wanted to grow his church, build a larger building, or expand to a new neighborhood, the universally agreed upon course of action was simple: host a revival.

3. Justification by numbers

A third consequence was an increased reliance on numbers as the barometer of success. When Payson concluded the revival in Washington, he complained that the work had begun slowly, and the meetings had not been as crowded as he had hoped.[19] But Washington pastors were pleased by the increases in membership they saw in their churches as a result of the revival. First Congregational Church reported that they had added 170 members during Hammond’s campaign, including 115 on a single Lord’s Day.[20] Calvary Baptist saw their church membership increase from 381 to 505.[21]

But these short-term additions masked long-term challenges. For instance, in a study of New York revivals, historian Curtis Johnson found that members who joined churches during revivals, on average, were excommunicated at a faster and higher rate than members who joined outside of revival services.[22] At Metropolitan Baptist Church, which continued the revivalistic practices throughout the 1880s, 45 percent of members baptized during revival meetings between 1884 and 1888 were eventually dropped from membership because they had stopped attending services.

CONCLUSION

The Washington revival of 1876 gives a vivid picture of the extent to which modern revivalism impacted and infiltrated American evangelicalism. As churches across many denominations bought into revivalism’s promises and adopted revivalism’s methods, they stopped looking for long-term indicators of success, such as perseverance and spiritual growth. Instead, they were after something else: a boost in membership that would validate the effectiveness of their ministry.

Sadly, such short-term perspectives often neglected long-term concerns. The same is true today. As we consider the mixed fruit of modern evangelicalism, pastors need to understand that the origin of many of our practices can be traced back to the revivalism of the nineteenth century.

[1] Iain Hamish Murray, Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism 1750-1858 (Banner of Truth Trust, 1994), xviii.

[2] Iain Hamish Murray, Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism 1750-1858 (Banner of Truth Trust, 1994).

[3] According to Dr. Rankin, of First Congregational Church, these were Dr. Mason Noble of Sixth Presbyterian Church, Dr. E. H. Gray of Fourteenth Street Baptist Church, Dr. S. Domer of St. Paul’s English Lutheran Church. Rankin does not name the fifth, but it seems likely that it was William S. Hammond of the Ninth-Street Methodist Protestant Church (Everett O. Alldredge, “Centennial History of First Church 1865-1965,” n.d., https://www.firstuccdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/fccucc-centennial-history1.pdf).

[4] As the National Republican explained, “A general committee of arrangements was appointed, consisting of Rev. Drs. Cleveland, Rankin, Gray, Noble, Domer, B.P. Brown, W.S. Hammond, Messrs. J.C. Harkness, Wm. Stickney, F.L. Moore, President Gallaudet, C.H. Merwin, F.H. Smith, Warren Choate, A.T. Steward, Dr. Presbery, S.S. Bryant, and B.H. Steinmetz” (National Republican, 2 Feb 1876, Page 4).

[5] Bentley was described by the National Republican as “a musician with “considerable reputation for efficiency in singing the Gospel” (National Republican, 2 February 1876, Page 4).

[6] The Reaper and the Harvest: Or, Scenes and Incidents in Connection with the Work of the Holy Spirit in the Life and Labors of Rev. Edward Payson Hammond, M.A. (Funk & Wagnalls, 1884).

[7] National Republican, 19 May 1876, Page 4.

[8] In her study of revivals in the United States, Kathryn Long found that “newspapers played a major part in shaping the images of most, if not all, the well-known revivalists after 1858.” Kathryn Teresa Long, The Revival of 1857-58: Interpreting an American Religious Awakening (Oxford University Press, 1998), 29.

[9] National Republican, 10 Feb 1876, Page 4.

[10] The reaper & the harvest, vii.

[11] McCloughlin, Modern Revivalism, 157.

[12] It is unfortunate that the biography of E.P. Hammond by Phineas C. Headley omits his time in Washington, only stating that “several years, including that in which he labored in Washington, D.C., have been omitted almost entirely. At some future time, it is hoped, another book will be written, giving an account of these harvest scenes.” Phineas Camp Headley, The Reaper and the Harvest: Or, Scenes and Incidents in Connection with the Work of the Holy Spirit in the Life and Labors of Rev. Edward Payson Hammond, M.A. (Funk & Wagnalls, 1884), 537.

[13] According to the National Republican, the gospel, as preached by Hammond, was as follows: “Jesus, the son of God, created this beautiful world we live in. The laws that God devised for the government of his children were broken by them, and they came under a penalty for their transgression. Jesus then stepped forth and offered to pay the penalty by his sufferings and death. He came down into this world, took upon himself the nature of ward, and died that we might live. He was forsaken by his father, that we might not be forsaken. He was treated as a sinner that we might be freed from the penalty of our transgressions. He died and ascended into heaven. But he will come again to earth and judge all, and separate the good from the evil, the righteous from the wicked.”

[14] National Republican, 3 Apr 1876, Page 1.

[15] In his study, Revivalism and Cultural Change, George M. Thomas has found that the prevalence of revivalism corresponded with greater support for the Republican and Prohibition parties. He offers the interpretation that religious movements, like those of the ‘Second Great Awakening,’ “articulate a new moral order and that each attempts to have its version of that order dominate the moral-political universe.” See George M. Thomas, Revivalism and Cultural Change: Christianity, Nation Building, and the Market in the Nineteenth-Century United States (University of Chicago Press, 2019), 2.

[16] The New York Daily Herald reported “over 2,000 converts” (See New York Daily Herald, 03 Sep 1876, Page 4).

[17] McLoughlin, Modern Revivalism, 156-157.

[18] “District of Columbia Population History,” Washington DC History Resources (blog), August 30, 2014, https://matthewbgilmore.wordpress.com/district-of-columbia-population-history/.

[19] Evening Star, 23 Nov 1876, Page 4.

[20] Everett O. Alldredge, Centennial History of First Congregational Church 1865-1965, p. 28-29. https://www.firstuccdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/fccucc-centennial-history1.pdf. This number is confirmed by the National Republican, which wrote on May 9, 1876, “Large accessions to the various churches were made on that Sabbath—over one hundred uniting with one of the churches” (National Republican, 09 May 1876, Page 4).

[21] Tiller, At Calvary, p. 16.

[22] Curtis D. Johnson, “The Protracted Meeting Myth: Awakenings, Revivals, and New York State Baptists, 1789–1850.” Journal of the Early Republic 34, no. 3 (2014): 355. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24486904.