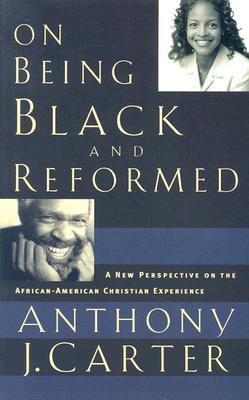

Book Review: On Being Black and Reformed, by Anthony Carter

March 3, 2010

March 3, 2010

The subject of racial healing has been widely discussed in both secular and church arenas since the formation of our nation. Many have grown tired of “addressing racial issues,” while others give only predictable and simplistic assessments. Entering this conversation is author and speaker Anthony Carter, who offers a fresh perspective on the African-American experience. Whether your faith is practiced in an African- or Anglo-Christian context, Carter’s work should help you in the work of reforming your church and bringing greater visible reconciliation to God’s people.

The author aims to answer two basic questions regarding the African-American experience: “Where was God during the Atlantic slave trade and American slavery?” and “How does Christianity triumph among an oppressed people who received their oppression at the hands of a so-called Christian nation?” While members of both black and white communities have asked these questions before, Carter considers them from the perspective of the Reformed faith.

Broadly speaking, Carter views the birth and development of the black church as a testimony to the sovereignty of God, a theme which serves to explain why he believes the Reformed faith is a natural fit for understanding the African-American experience. In addition to the doctrine of God’s sovereignty, Carter points to the biblical doctrines of sin and the sufficiency of Christ for explaining how humans can be so cruel to one another and how an oppressed people can embrace the religion of their oppressors.

Carter’s ability to answer pertinent historical questions allows him to provide the reader with a well reasoned, historical, and biblical response. It is his contention that we are to understand history helps us understand God and his character. Since God is the mover of the universe, studying history through the lends of Scripture helps us to trace what God is accomplishing.

Chapter one is devoted to answering a question posed by one of Carter’s seminary professors: “Is it necessary to have a black theology?” It’s a question that has been raised by many white evangelicals, and suggests that they are unjustifiably suspicious of anything pertaining to the black Christian experience. Carter responds to the professor’s question by rephrasing it in such a way that the reader can see what’s at stake: “Do we need to understand the African-American experience through a theological perspective that glorifies God and comforts his people?” The answer to this question must be “emphatically” and “unfortunately” “yes” (3)! The answer is emphatically yes because of the need to present an alternative to unsound, unbiblical black theological perspectives, like the black theology movement of the 1960s. The church needs a theology that can speak to the African-American experience from a redemptive historical context.

The answer must also be emphatically yes because “theology in a cultural context has not only been permissible, but has now become normative.” It’s the tendency of the majority culture to view its own perspectives as neutral and normative. But no perspective is ultimately neutral or normative. In order to be theologically honest, Carter argues, we need to acknowledge that our theologizing emerges out of a certain context. David Wells seems to do as much when he acknowledges that American theologizing bears distinctly American characteristics (5)

However, Carter answers the question of whether we need to understand the African-American experience through a theological perspective with an unfortunate yes. It is unfortunate “because conservative Christians have failed to grapple with issues of African-American history and consciousness, especially in the areas of racism and discrimination.” Because of this failure, an African-American perspective on theology is mandatory (6).

In chapter two, Carter brings three basic biblical truths highlighted by Reformed Christianity to bear on the topic of racial reconciliation: the sovereignty of God, the sinfulness of humans, and the sufficiency of Christ. Carter begins with the picture of God sovereignly working out his plan in our lives for his glory and our good. Then he points to our need for the Savior by considering the extent of human depravity and the hopeless of fixing our behavior through the various sociological, economic, or educational remedies (and the philosophies behind them).

Only in Christ is the cure for sin found. In God’s gracious forgiveness of us we are provided with the strength to forgive others (Matt. 6:12; Eph. 4:32). As a testimony to this kind of power, the book wonderfully documents many African-Americans responses to oppression that were grounded in the Christian principles of love and forgiveness.

Chapter three provides a historical response to the question, “How could African-Americans embrace the same Christ that their oppressors professed?” while chapter four answers the inquiry, “Is the black Christian experience incompatible with the reformed tradition?” (46, 70). Carter serves the reader well in answering the initial question by tracing God’s hand in the building of the African-American church from the onslaught of slavery to the birth of the first African-American churches in 1794 under the leadership of Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. He then helps us witness God’s providential hand behind the cruelty of slavery from the founding of the first African-American denomination in 1816 to the present re-Africanization of Christ’s bride (Gen. 50:20). In spite of all of their trials, blacks were able to discern the truth of the Christ of Christianity while rejecting the unbiblical practices of misguided Christians.

In chapter four, Carter calls upon all believers to accept the truth that “God’s kingdom comprises a diversity of people with a common heritage.” He cautions us against racial pride by helping us to understand that “our common heritage is not primarily black, white, or brown, but our heritage is rooted in redemptive history. It is instructive to see that the history of redemption is not black history, white history, African or European history—it is God’s history” (63). Carter does his best work in chapter four as he responds to the question, “Is the black Christian experience incompatible with the reformed tradition?” Carter argues against the traditional view that the black experience of Christianity was not compatible with a Reformed faith. He contends that white Christians took such a position because of their support of slavery and that American theology is incomplete if it fails to include the contributions of blacks. A long list of Christian black leaders (the people of Libya and North Africa in Acts 2, Augustine, Athanasius, Jupiter Hammon, Lemuel Haynes, Phillis Wheatley, John Marrant, etc.) are listed as evidence that God is not a respecter of persons when it comes to reaching all nations with the gospel.

On Being Black and Reformed is an excellent introduction to the African-American experience from the perspective of redemptive history. Any believer who seeks a greater appreciation of God and his sovereign ways will find the book a valuable read. African-Americans who read this book will be compelled to seek a better grasp of Reformed Christianity, while white Americans who read it will gain a much richer insight into American history and theology. I highly recommend Carter’s book.