Too Young to Dunk? An Examination of Baptists and Baptismal Ages, 1700–1840

June 21, 2021

June 21, 2021

These days, it’s common for people to get baptized at 10 or younger. This is true across many credo-baptist traditions, but perhaps especially so among Baptists. How does our current practice square with Baptists of the past? In this article, the third in a three-part series, we’ll examine that important question.

With the help of William Buell Sprague’s Annals of the American Baptist Pulpit, I can examine the accounts of 45 baptisms from 1700 to 1840. Hopefully, this will provide useful insights into how children relate to the church and, perhaps more to the point, when they should be put forward for baptism.11 . These accounts are taken from William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Baptist Pulpit, a compilation of biographies written on the leading Baptists in America who died before the 1850s. “Annals of the American Baptist Pulpit” is Volume 6 in a series of nine volumes edited by William Buell Sprague (1795–1876) and published between 1858 and 1869. They contain “commemorative notices of distinguished American clergymen of various denominations from the early settlement of the country to the close of the year eighteen hundred and fifty-five, with historical introductions.” As such, it is considered one of the great classics of biographical church history. Log College Press has graciously made the entire series available online at https://www.logcollegepress.com/william-buell-sprague/?rq=sprague. I’ll briefly discuss the data before providing four reflections.

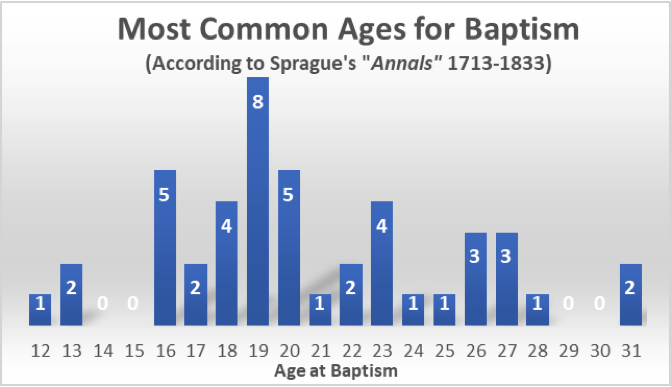

As the chart below shows, the most common age for baptism was 19. The youngest subject was a 12-year-old; the oldest was 31. If these 45 examples are representative of Baptist practices from that time period, the rough “bell-curve-shape” indicates that people were ordinarily baptized in their late teens or early twenties.

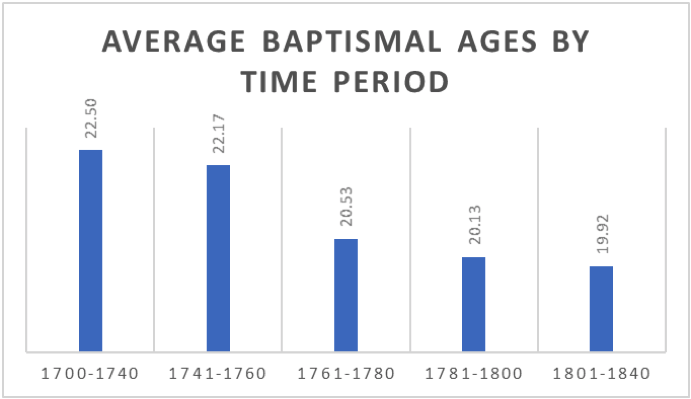

As the chart below shows, this pattern roughly holds across time. The age only slightly lowers over nearly 150 years. In total, the average baptismal age came to 20.68.

These numbers provide four lessons from the past on the often-thorny topic of age and baptism:

Time and time again, biographies in Baptist history repeat the language “baptized into membership.”

I could go on. The point is clear: baptism and membership go hand-in-hand. When you’re baptized, you’re baptized into a particular body of believers: a local church. Unheard of in those days was separating of baptism from church membership.

We see how baptism and membership went together in the life of Noah Davis (1802–1830). Davis was raised in a Baptist household in Salisbury, Maryland, and baptized just before his 17th birthday on July 4, 1819 (702). He gives the following account of his baptism:

The administration of the ordinance of Baptism in Sansom Street Church had several times a very powerful effect upon my mind. . . . I mentioned my exercises [experience of grace] to Mr. Fassitt, at the same time requesting him to state my case to Dr. Staughton, who was then Pastor of the Baptist Church in Sansom Street. This he did, giving the Doctor an account of my experience, with which he appeared to be satisfied. After examination, the church consented that I should be baptized at their next regular meeting, which took place July 4, 1819. . . . In the afternoon of that day, I was received into the visible church by the Right Hand of Fellowship, presented by Dr. Staughton, the Pastor; and, for the first time, partook of the Lord’s Supper. Oh what a day to me! With what regret should I remember how poorly I have sustained the profession then assumed. In the church of which I became a member, I found the interchange of religious affections most delightful; the services of the sanctuary became interesting, and I could sing! (702)

Davis’ case follows the pattern ordinarily practiced in Baptist churches: (1) sharing one’s experience of conversion with the pastor, (2) examination by the church, (3) the church gives consent for baptism, (4) baptism, (5) reception into church membership, and (6) participation in the Lord’s Supper. This is the ordinary pattern for baptisms in Baptist churches from 1700–1840. (For reasons churches shouldn’t practice spontaneous baptisms, see my article here.)

One implication of the inseparable relationship of baptism and membership is that you should never baptize someone into membership whom you would not excommunicate. Excommunication refers to barring someone from the Lord’s Supper for unrepentant or scandalous sins. Sprague’s Annals of the American Baptist Pulpit shows that Baptists were to exercise that responsibility, even when the subject was a teenager.

For instance, the youngest baptism mentioned is Elisha Tucker (1794–1852) who was baptized at the extraordinary age of 12 in 1806 by Rev. Levi Streeter when he “was supposed to be converted” (668). However, two years later Tucker was excommunicated from the church at age 14 for yielding “to the temptations to worldly gaiety and pleasure” (668). It was not until six years later, at the age of 20 that Tucker “recovered from his wanderings, and was restored to his relation in the church” (668).

The same pattern played out in the life of John Tripp (1761–1847) of Massachusetts who, after becoming “deeply interested in the subject of religion” at the age of 11, was baptized at the early age of 13 by Rev. Ebenezer Hinds and “admitted to the church” of Middlesbrough, MA (278). However, for several years afterward he lived an immoral life. It was not until 1780, at age 19, that he was awakened to his “spiritual declension,” leading him to make a “profession of his faith” and a renewed commitment to the church (278).

These instances of exercising church discipline against members who were baptized as pre-teens or young teenagers should serve as a warning. Sprague’s Annals only documented three individuals baptized before the age of 16—and two of these three were later subject to church discipline.

Thus baptism, like membership, is not something to be taken lightly. Nor were churches unwilling to follow the biblical pattern laid out in Matthew 18:15–20 and excommunicate even teenagers who weren’t walking in step with the church covenant.

In light of these examples from the past, it might be worthwhile to examine the average baptismal age at your church. If it’s far different from past generations of Christians, might it be worthwhile to ask why?

Taking the requirements of church membership seriously and working to restore the practice of church discipline might mean steadily raising the average age of baptisms in your church. I am assuming here that it is not sinful to delay baptism. As Mark Dever has written, while “the Bible gives us no command for immediacy or for delay, the nature of baptism clearly shows that it’s only for those who profess saving faith. Therefore, if delay is necessary to ascertain genuine saving faith, then delay would seem to be the path of prudence.” 22 . Mark Dever, Believer’s Baptism, 345.

This didn’t seem controversial to Baptists of past centuries—even to those in ministry. John Gano Wightman (1766–1841), the son of Baptist minister Timothy Wightman, was trained in “the best character” but not “baptized into the fellowship of the church” until the age of 31 when he “became hopefully pious.” (30).

Despite being the subject of “early religious impressions,” Abraham Marshall (1748–1819) was not “united” to the church until he had reached his twentieth year (169). Even Jesse Mercer (1769–1841), who experienced “serious impressions” in childhood to the point of having “no intermission of anxiety” in respect to his salvation from ages 14–18, wasn’t baptized until 18 (284).

If Baptists in the past were content to wait on God’s timing and adequate evidence of conversion before administering baptism, then why aren’t we?

These cautions notwithstanding, one of the joys of reading the baptismal testimonies from Sprague’s Annals was reading the accounts of young believers being converted and baptized. One such example is the story of Thomas Ustick.

Ustick (1753–1803) was raised in the Episcopal Church but encountered the First Baptist Church of New York pastored by John Gano at 13 when working for his uncle. He was converted and was “little more than thirteen years of age, when he was baptized, on a profession of faith, by the Rev. Mr. Gano” (165) and became “a member of the Baptist Church” (166). This was truly a singular event, for Rev. Gano even changed the words of the hymn to be sung on the occasion so that it read “His honour is engaged to save / the youngest of his sheep” (165). The original words of Isaac Watts’ “Firm As The Earth Thy Gospel Stands By” meant that Gano had changed for the occasion (165).

Although young to be baptized, his biographer demonstrates that Ustick showed clear evidence of conversion and conviction to follow Christ whatever it may cost him: “His uncle, with whom he lived, was a decided Episcopalian, and could not give his consent that he should connect himself with any other than the Episcopal communion; and he even meditated the purpose of confining him to his chamber, during the day on which he was baptized” (166). Nevertheless, Ustick risked his reputation, his future, and his family’s displeasure to follow Jesus.

Baptismal ages is one of those topics fraught with difficulty and challenges for churches, pastors, and parents. I hope that these examples from the past can provoke honest assessment of our own practices and convictions so that we neither harm the faith of Christ’s sheep by excessive scrutiny, nor harm Christ’s church by carelessness.