Week 2—What Christians Should Do For Government: Obey Scripture, Get Wisdom

Editor’s note: This is the manuscript from the second week of Jonathan Leeman’s adult Sunday School class “Christians and Government,” which he is currently teaching through at Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, DC. There will be 13 weeks in the class. Here is the course schedule, to be published as it’s taught.

What Christians Should Do For Government

Week 1: Love Your Nation, People, or Tribe

Week 2: Obey Scripture, Get Wisdom (manuscript below)

Week 3: Be the Church Together

Week 4: Be the Church Apart

Week 5: Engage with “Convictional Kindness”

What Christians Should Ask of Government

Week 6: To Not Play God

Week 7: To Establish Peace

Week 8: To Do Justice

Week 9: To Punish Crime, Tax, and Defend the Nation

Week 10: To Treat People Equally (Justice and Identity Politics)

Week 11: To Provide Space for True and False Religion

Week 12: To Affirm and Protect the Family

Week 13: To Protect the Economy

* * * * *

Should a Christian be for or against gun control? For or against environmental protection policies? For or against universal health care, and the wealth redistribution this typically requires via higher taxes. What about graduated or progressive tax rate based on income?

Which party should a Christian belong to? Can a Christian be a divorce lawyer?

Should a Christian vote when he or she only has a choice between a candidate who represents injustice X and one who represents injustice Y?

How should a Christian in government decide what is a crime and what the punishment should be? Not all sin should be a crime, right? But when should sin be a crime? When shouldn’t it?

How do we persuade people with different worldviews than our own?

No, doubt, these are all tough and debatable questions. And part of what makes questions like these tough for Christians like us is determining how we should use the Bible when engaging with them. After all, as Christians we know that the Bible alone is God’s Word. Everything it says is true, right, and just. But there are at least three big problems:

- It’s silent on many/most political issues.

- How do we interpret it for politics? It’s a complicated book, written in multiple genres, set in different historical moments.

- It’s our book, not theirs (non-Christians). So can we really impose its truth claims on unbelievers?

The question we’re interested in today is, how should we use the Bible in politics?

The big-picture answer to that question is, Christians need to be able to know how to distinguish between law and wisdom, and how to be led by each. Things ordained by divine law we hold with firm grip in all times and places. Things left to wisdom we hold with a looser grip, knowing that the right path, to some extent, depends on time and place. You’ll notice the title of today’s class is “Obey Scripture, Get Wisdom.”

WHAT IS THE BIBLE AND WHAT DOES IT DO

We need to start with what the Bible is. Our church’s statement of faith, the New Hampshire Confession, says a couple of things about Scripture worth noticing for our purposes. Here is what you affirm about the Bible if you are a member of our church:

“We believe that the Holy Bible was written by men divinely inspired, and is a perfect treasure of heavenly instruction; that it has God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth without any mixture of error for its matter; that it reveals the principles by which God will judge us; and therefore is, and shall remain to the end of the world, the true center of Christian union, and the supreme standard by which all human conduct, creeds, and opinions should be tried.”

It Gives God’s Supreme Standard of Judgment for All

First, it says the Bible is “the supreme standard by which all human conduct, creeds, and opinions should be tried.” The Bible gives us “truth without any mixture of error,” says our statement, and “reveals the principles by which God will judge us.”

It’s claims like these that tell us that we should go to the Bible, somehow, when it comes to thinking through political issues. The thinking is, “The Bible gives us God’s perfect Word; it’s the supreme standard for all human conduct. Shouldn’t we therefore consult it when thinking about, uh, everything from trade policy to carbon dioxide emissions to public education?” And in one sense, this is correct. Listen to Revelation 7:15-17:

“Then the kings of the earth and the great ones and the generals and the rich and the powerful, and everyone, slave and free, hid themselves in the caves and among the rocks of the mountains, calling to the mountains and rocks, ‘Fall on us and hide us from the face of him who is seated on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb, for the great day of their wrath has come, and who can stand?’”

Why will the kings and generals and every political class (slave and free) fear the coming of Christ’s wrath? Because they did not use their political stations, whether high or low, to live and rule perfectly according to his word.

It doesn’t matter if a majority of the American public, the justices of the Supreme Court, and the U. S. Congress do not acknowledge God or God’s Word. He is their God, and he will judge by his standards, not theirs.

In other words, the relevance of the Bible to politics depends entirely upon the judgment of God. Take away God’s promised judgment and the Bible has no relevance. So in some ways it doesn’t matter whether or not people acknowledge the Bible is “their” book. It matters only whether or not God will judge.

Does that mean we impose the whole Bible on them? Not necessarily. But it does mean we must give close attention to what the Bibles says government should and should not do. It also means we should never personally put our hands to anything that will earn God’s judgment, even if people want to make it legal.

That said, the purpose of Scripture is not to be a political operator’s manual, which brings us to a second claim in our church’s statement of faith.

It Has Salvation As Its End and Is the Center of Christian Union

Our statement of faith affirms that the Bible “has salvation for its end” and is “the true center of Christian union.” It doesn’t say the Bible “has good civil government for its end” or “heaven on earth for its end” and is “the true center of national and civic union.” In other words, the Bible isn’t a political strategy book or a legislative manual.

Ask yourself this question: what form of government does the Bible say is best—democracy, aristocracy, or monarchy? It doesn’t, and if you trace the history of Israel, you’ll see that God himself employs multiple forms of government at different times to govern his people: patriarchal family structures from Abraham to the Exodus, judges from Moses to Saul, then a monarchy, then the assembly structures (qahal) when in exile under the Babylonian empire. So if you were sitting at the American constitutional convention, how would you use the Bible to make your case? And what would your case be?

So while the first thing we said about Scripture makes some people want to say the Bible is a political book, it’s this point that makes some people say that it’s not at all a political book. And of course both points are true in their own way.

WE NEED TO BE ABLE TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN LAW AND WISDOM

It’s these two facts about the Bible that put us in the position of needing both law and wisdom. On the one hand, the Bible is the supreme standard, and where it does speak in binding ways, both we and all humanity are bound. That’s law. On the other hand, the Bible’s purpose is not to build up an empire or a nation state, though it provides principles for understanding human life in all its domains. That’s why we need wisdom.

What is the relationship between law and wisdom?

First of all, law is absolute and unchanging. I don’t care what nation or century you live in, you shall not murder. You shall not steal. Most if not all Christians would agree those two commands belong in the law bucket, whether or not a person acknowledges Christ or God.

Matters of wisdom, on the other hand, are not necessarily matters of complete moral indifference, like, should I have Wheaties or Cornflakes for breakfast? Rather, they are matters that will make a difference in the peace, order, and flourishing of human lives, and do involve a number of moral principles, but the solution is not biblically prescribed or specified as a law; and the path to that solution is a complex moral calculation over which people might disagree.

Suppose a government wants to build a train track from city A to city B. But following the topography one way will require them to go through mountainous terrain and put many lives at risk, while following the topography in another way will require them to build a series of bridges through marshland and will come at exorbitant costs, which means higher taxes. What’s the biblical solution? Well, there are biblical principles we bring to bear on the question, but the answer finally depends upon a number of complex calculations involving a host of moral and practical variables.

The relationship between law and wisdom, I think, can best be likened to the relationship between the rules of a game and the strategy you employ to win a game. You have the rules of football; those are fixed. And then you have the coach and quarterback’s calculations about how to beat this team on this day on that field. Do you use the running game or the passing game? That’s wisdom.

LAW, WISDOM, AND CHURCH ENGAGEMENT

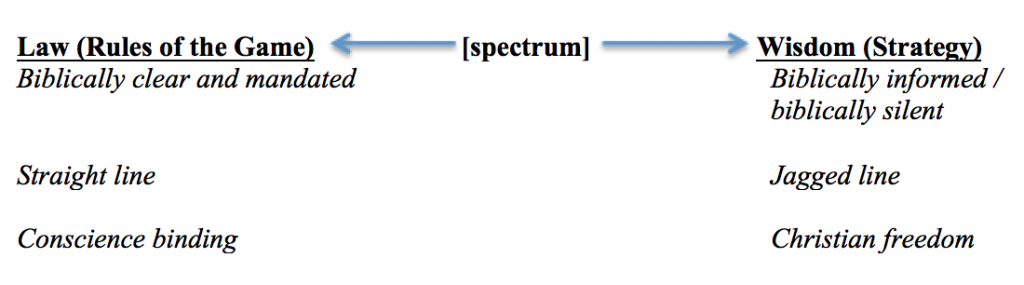

Recognizing the distinction between matters of law and wisdom is crucial for knowing when and whether churches should address issues in the public square. Robert Benne, in his very helpful book, Good and Bad Ways to Think About Politics and Religion, refers to those issues in which there is a straight line from core biblical principles to political policy applications, and those issues where there is a complex and jagged line.

I would argue, for instance, that there is a direct path from biblical principle to political application with abortion. Abortion is murder, and the Bible commands governments to protect its citizens from murder. The path is basically that simple. As an isolated issue, abortion is different than, say, education or health care policy. Christians might have principled convictions about these latter issues, too, but most would admit that the path from biblical principal to political application is more jagged, dim, and certainly debatable.

Now, admittedly, even with something like abortion, questions of political strategy and implementation are still in play. Just because we agree it’s wrong doesn’t determine which is the best legislative or judicial strategy in stopping abortion. One Christian might argue for one strategy and another for another. Even here, then, wisdom is needed.

Still, broadly speaking, we can say that issues where biblical law are at stake tend to be straight-line issues. Issues where the path between biblical principle and policy application is jagged are issues for wisdom.

Obviously, it’s not always clear what issues are law issues and what are wisdom issues. Yet there is surely something of a spectrum, and as we consider this spectrum we can get some sense of how churches should or shouldn’t formally engage in public square matters.

For starters, we can say things are law for all humanity when something is biblically clear and mandated, like the command not to murder. But when the Bible is silent on something, we can have a biblically informed conversation, but it’s more likely to be a topic on which Christians should be able to disagree. Education policy might be an example. To be sure, there’s a spectrum in between straight line and jagged line issues. On one side we bind consciences, on the other side we don’t. It’s a matter of Christian freedom.

Church Formally Involved Directly or Indirectly (left side of spectrum)

– Pastoral speech

– Condition of membership and discipline

– Tied to the name of Christ

Members involved on both sides (right side of spectrum)

– Pastoral silence

– No condition

– Not tied

The more a matter falls on the law side of things, the more the church will institutionally address a matter. For instance, pastors might talk about it. You might even exercise discipline on a matter or make it a condition of membership. The more something falls on the wisdom side of things, the less pastors should lend their pastoral weight to addressing the matter, and Christians on both sides of an issue should be made to feel welcome. So for example, party membership typically falls onto the wisdom side of the spectrum. But now suppose it’s 1941 and our church is in Germany. I think a pastor would be well within his biblical authority to oppose in a sermon the Nazi Party since it called for complete and idolatrous allegiance to Hitler. And a church would be well within its biblical rights to excommunicate a Nazi Party member. But let me again make a qualification about pastoral speech. Just because a pastor knows that something is biblically right or wrong on a straight-line issue doesn’t mean he should propose policy solutions. That would be outside his expertise and authority and subject to the wisdom of those with more competence in those areas, whether Christian or non.

A Few Topics (left side of spectrum):

– Necessary for mission of the church

– Expectation of non-Christian opposition

– Grounds for revolution or departure!

Most Topics (right side of spectrum):

– Desirable, perhaps, but not necessary for mission

– Expectation of non-Christian competence

– No ground

There are only a few topics that I think we can put on the law end of the spectrum, specifically, those issues pertaining to life, family, and religious freedom. By “life” I’m not primarily talking about the social issues like abortion, though that’s an implication. I’m primarily talking about the basic call of government in Genesis 9 to render judgment and preserve the lives of its citizens so that the Cains stop killing the Abels. Family, too, is a creation ordinance—Genesis 1, 2, and 9. And religious freedom is a creation matter for reasons we’ll discuss in future weeks. Ironically, we can expect oppositions from non-Christians at the law end of the spectrum, while at the wisdom end of the spectrum, we can expect non-Christians to be quite competent, sometimes even more competent than Christians due to common grace. Also, we’ll talk about revolution or rebellion in a future week, but very briefly, if there are grounds for overthrowing or at least disobeying a government, it will be in matters on the law side of the spectrum, less so on the wisdom side.

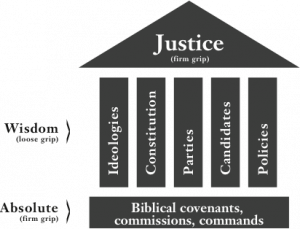

A chart that shows how some of this plays out, and that we’ll examine more in future weeks is this:

We should keep a firm grip whenever biblical covenants, commissions, or commands are clearly involves, as well as in the pursuit of justice generally. We should keep a relatively loose grip in matters of constitutions, parties, candidates, and specific policies. These depend on wisdom.

So that’s the big distinction that will guide how we think about applying the Bible to politics and policy. Like I said before, most of the issues we deal with day to day are on the wisdom side of the spectrum.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF WISDOM TO POLITICS IN SCRIPTURE

Wisdom is absolutely crucial to politics in life and in the Bible. In fact much of the conversation about Christianity and politics occurs over here in wisdom territory, and you can see this pretty clearly in wisdom literature.

Turn to 1 Kings 3. God asks Solomon, “Ask what I shall give you.”

Solomon answers in verse 9: “Give your servant therefore an understanding mind to govern your people, that I may discern between good and evil.” He asks for understanding or wisdom.

Immediately the narrator tells us a story demonstrating exactly this. In verses 16 and following two prostitutes come to the king claiming that a baby is hers. Solomon says in verse 25, “Divide the living child in two, and give half to the one and half to the other.” The lying prostitute says “Fine.” The real mother says, “No, give the child to her.” And now everyone knows who the real mother is. Verse 27: “Then the king answered and said, ‘Give the living child to the first woman, and by no means put him to death; she is his mother.’”

Then look at how the narrator summarizes the story. Verse 28: “And all Israel heard of the judgment that the king had rendered, and they stood in awe of the king, because they perceived that the wisdom of God was in him to do justice.”

Friends, right there you have the Bible’s political philosophy in a nut-shell: kings, congressman, diplomats, generals, police-officers, voters, judges, and jurors need wisdom…to do justice. But not just any wisdom—we need the wisdom of God to do justice. Forget reading Plato and Aristotle, Locke and Hobbes. Read that one verse.

Or turn to Proverbs 8 [NIV 2011]:

1 Does not wisdom call out? Does not understanding raise her voice?…

4 “To you, O people, I call out; I raise my voice to all mankind.

Who does God expect to act according to wisdom, whether or not they believe the Bible or have even met a Christian? “All mankind.”

15 By me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just;

16 by me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth….

Is wisdom calling just to the kings of Israel? Which rulers need her? “All whole rule the earth.” The Maryland State House. The DC Department of Public Works. The FCC. How will rulers like these prosper and succeed in what they do, and facilitate the prosperity of those whom they serve? By wisdom.

But how can this be if these leaders do not acknowledge God? Are Ted Cruz, Nancy Pelosi, Clarence Thomas, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg really called to walk according to God’s wisdom? Does their success really depend upon this wisdom that begins with the fear of the Lord? How could this be? Look at verses 22 to 30. God’s wisdom provides the very fabric of creation. To go against his wisdom is to go against creation’s very design pattern. Wisdom helps us live “according to the warp and woof of the world.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE LAW/WISDOM DISTINCTION FOR CHURCH UNITY

I hope you see how crucial it is to maintain these two categories for unity in the church. So much political dialogue among Christians these days thoughtlessly and divisively treats everything as a law issue. Whether in private conversations among friends or public conversations in the blogosophere, how often have you heard Christians talk as if their position on health care or tax policy or immigration or foreign policy is the only acceptable Christian position, as if to say all other positions are sin. Wow! Way to raise the stakes and effectively excommunicate everyone who disagrees with you. Way to make your political calculation on such-and-such political issue the standard of righteousness. Where something is explicit in the Bible or at least clear “by good and necessary consequence,” as the Westminster Confession puts it, let’s be explicit and clear. But where the Bible isn’t explicit and clear, we generally need to leave room for Christians to disagree with us; leave room for Christian freedom.

So ask yourself: is such-and-such issue a law issue or a wisdom issue? If it’s a wisdom issue, yes, make arguments. Attempt to disciple, even persuade. I’m not saying wisdom issues are unimportant, or that questions of justice aren’t at stake. I’m just saying that you don’t have apostolic powers, and that you should be very, very reluctant to bind the conscience where Scripture does not. Be very, very reluctant to say “This is the Christian position” or “A Christian must vote this way” unless you are (almost) ready to recommend excommunication over taking the wrong position. Leave wisdom issues in the Christian-freedom bucket, and engage charitably.

If you don’t, you may well divide the church where the Bible does not, and one day you will have to give an account to King Jesus for that. You’ve heard the saying, “In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, in all things charity.” That’s a good rule of thumb.

WHAT IS WISDOM IN THE BIBLE?

So what is wisdom?

A Right Posture. Biblical wisdom, first of all, is a right posture—the posture of fearing God. Look again at Proverbs 9:10: The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom;

Fear of the Lord is the recognition that he is the one who has established the rules. Wisdom tells us to vote, legislate, picket, judge, lobby, prosecute, write and give speeches all in relationship to God’s understanding creation, God’s understanding of humanity, God’s understanding of morality and justice, God’s understanding of himself and the final judgment.

A Skill. Biblical wisdom, second of all, is the skill of discernment. It is the skill of living successfully by discerning right from wrong, or valuable from worthless, or productive from unproductive, in God’s created but fallen world.

Wisdom is the skill of knowing people and what they are made of, and a decent sense of how they are going to act under certain circumstances. It requires the ability to know the moral ideal, and to balance it with the politically realistic. It requires an understanding of the legislative game and how to get laws passed or indictments made.

Here are a few examples:

- 1) Proverbs 10:4 reads, “Lazy hands make for poverty, but diligent hands bring wealth.” A wise ruler, no doubt, will look for ways to maximize industry, and not reward laziness. Certainly this has implications for welfare policies.[1] How easy it is for a nation’s welfare policies to abet laziness and so exacerbate poverty. At the same time…

- 2) Proverbs 29:7 reads, “The righteous care about justice for the poor.” And 29:14 says, “If a king judges the poor with fairness, his throne will be established forever.” A good king, like a good shepherd, doesn’t leave some of the sheep behind. He seeks to bless and benefit all. He is going to judge them and their circumstances with fairness. He is going to consider the causes of poverty, and ask what might contribute to entrenched cycles of poverty.

Wisdom, then, is about putting these last two points together. I don’t want to promote policies that incentivize laziness, but I also want to consider various structural inequities that create cycles of poverty and do justice for those stuck inside of them. - 3) Proverbs 29:4: “By justice a king gives a country stability, but those who are greedy for bribes tear it down.” My understanding is that laws in this town are fairly strict concerning gifts to congressmen and senators. And we know the limits on campaign finance are also fairly strict. Whether or not you agree with these particular measures, praise God we live in a nation where it’s considered unethical and illegal to take a bribe. That is good for our nation. Just ask our representatives in Iraq or Afghanistan who easy it is to establish a government when accepting bribes is a way of life.

There are a lot more examples that we could give of wisdom in motion.

HOW THEN DO WE READ THE BIBLE FOR POLITICS?

Let me offer a last few comments on reading the Bible for politics.

To take a simple example: we can have a real life situation, say, immigration problems, and someone wondering how Scripture might inform our immigration policy. So he digs back into the Old Testament and discover God’s words to Israel about showing compassion to foreigners by reminding they were once exiles and foreigners. “Ah,” the zealous young Christian concludes, “The Bible supports what I want to say about immigration policy.” Does it?

Or suppose a Christian congressman reads Proverbs 22:7 in their quiet time—“the borrower is a slave to the lender”—and becomes convicted to advocate for laws that abolish all lending? Would that be a good use of Scripture?

How do we read the Bible “politically”? A few quick principles.

1) Ask which covenantal audience the author has in mind.

At the risk of over simplification, we can say that Genesis 1 to 11, in some sense, are directly applicable to all humanity. Genesis 12 to the end of the Old Testament are directly applicable to ancient Israel. And the New Testament is directly applicable to the church, with some exceptions made for the transitional nature of the Gospels and Acts.

Now, all the Bible is relevant for the church and all humanity in one sense, as we discussed above. But hear me out: The Bible is structured by covenants, both common and special. The common covenants were given through Adam and Noah. The special covenants were given through Abraham, Moses, David, and Jesus.

What’s critical is this: those covenants were given to specific groups of people. The Mosaic covenant, for instance, was given to the people of Israel. It wasn’t given to the Babylonians. It wasn’t given to you and me. Why aren’t we bound by the laws concerning shellfish or clothes made out of mixed material? Because it belongs to the Mosaic Covenant, not the New.

But what about the Ten Commandments, you ask? Well, who were they given to? Israel! They don’t apply directly to us, any more than the Chinese or Russian laws against murder or stealing apply to us as Americans. Now, it so happens that nine of the ten commandments get repeated in the New Testament (not the Sabbath). Not only that, all the Mosaic covenant has lessons for us! So I’m not saying we discard it. My only point is, the fact that the audience is Israel means I’m not going to apply any of its laws direction to myself, much less the nation state.

A similar principle applies to the New Testament. Jesus says to “Love your enemies” and “Turn the other cheek.” Does that mean the state should never go to war, or that policemen should never use force? No. Jesus intended audience here is members of the new covenant in their relationships with one another.

2) Ask what the author’s intention is.

Go back to Proverbs 22:7: “the borrower is a slave to the lender.” Is the author’s intention to set government housing policy? Not at all. It’s to signify certain subjective and objective realities that will accompany indebtedness, and to suggest that you might want to avoid it in many circumstances. At the same time, there are surely times when borrowing money is necessary. And a wise government might decide to get involved in various lending practices in order to protect the very ones whose circumstances require them to take out loans. So: ask what the author is saying and not saying, and to whom he is saying it.

3) Consider what God has specifically authorized government to do, and whether there is a precedent with universal normativity.

In future weeks we’ll talk specifically about what God has authorized government to do. What authority has he given to it? The answer, we’ll find, is in Genesis 9:5-6, with a useful elaboration in Romans 13 and in particular historical episodes such as Joseph or Solomon.

The point here is, anytime we’re considering a particular biblical principle, we want to ask the question, has God specifically authorized government to do that? He’s clearly authorized government with the right to render judgment when lives are at stake. Can we build a case for universal health care from that basic principle? Some might say yes; some might say no. We don’t need to answer that question right now, but that’s where the conversation needs to happen.

When we examine other biblical passages or principles, furthermore, we’ll want to hold it up against this primary question of what government has explicitly been authorized to do.

4) When it comes to the relationship between law and sin, our duty to the public square depends in part on whether something is being proscribed or prescribed, criminalized or subsidized.

Christians should never support laws that positively prescribe or subsidize sin. State lotteries, for instance, positively support and encourage gambling. So with same-sex marriage. It financially incentivizes and encourages sexual sin. That’s different from saying we should criminalize gambling or criminalize sexual immorality. Just because something is a sin does not mean we should criminalize it. Which sins should be criminalized? To answer that we’ll need to consider what God specifically commissions government to do, which we’ll do in weeks 7 and 8. The short answer, any activity which brings clear and positive harm on another human being should be criminalized, like murder, stealing, physical violence, and so forth. Obviously, it’s not easy to determine what constitutes harm. I’m just saying, that’s the conversation we need to have for figuring out which “sins” should be made criminal.

“And the people were amazed that God had given Solomon wisdom to do justice.” Finally, friends we and those in charge need justice. Let’s pray for wisdom.

* * * * *

Editor’s note: For a fuller description of Jonathan’s views on church and state, seePolitical Church: The Local Assembly as Embassy of Christ’s Rule (IVP, 2016).

FOOTNOTES:

[1] http://www.scribd.com/doc/172493289/Workforce-092913