Week 1—What Christians Should Do For Government: Love Your Nation, People, or Tribe

Editor’s note: This is the manuscript from the first week of Jonathan Leeman’s class “Christians and Government,” which he is currently teaching through at Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, DC. There will be 13 weeks in the class. Here is the course schedule, to be published as it’s taught.

What Christians Should Do For Government

Week 1: Love Your Nation, People, or Tribe (see manuscript below)

Week 2: Obey Scripture, Get Wisdom

Week 3: Be the Church Together

Week 4: Be the Church Apart

Week 5: Engage “Convictional Kindness”

What Christians Should Ask of Government

Week 6: To Not Play God

Week 7: To Establish Peace

Week 8: To Do Justice

Week 9: To Punish Crime, Tax, and Defend the Nation

Week 10: To Treat People Equally (Justice and Identity Politics)

Week 11: To Provide Space for True and False Religion

Week 12: To Affirm and Protect the Family

Week 13: To Protect the Economy

* * * * *

AN AMERICAN PROLOGUE

I don’t recall when first became conscious of the fact that I loved the United States of America. Maybe it was amidst the glint of sparklers on the fourth of July as a child; or during my third helping of sweet potato casserole at Thanksgiving; or watching a Cubs game at Wrigley Field. I do remember reading Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing” in college and being enlivened with love of country by it.

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear…

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else…

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

I also remember discovering the composer Aaron Copland in college whose ballets, orchestral suites, and folk themes evoke images of Appalachian songs and prairie nights and Western hoe-downs. To this day when I hear his music, I can feel a deep, yearning nostalgia for decades I’ve only read about, and places I’ve only seen in black and white photographs—but all deeply American.

Love of nation, people-group, or tribe is a fairly common thing, and probably has been since the beginning of human history. We recognize, of course, there are healthy and unhealthy forms of such love. What I’ve given you are simply some of the symbols of my own love of country.

What has been difficult for me over the last decade or two has been to watch a growing opposition in American culture and politics toward elements of my Christianity. Same-sex marriage is now the law of the land in all 50 states thanks to the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling, which has brought with it a number of challenges to religious liberty. And so an Orthodox Jewish university (Yeshiva) was required by courts to allow same-sex couples into its married dormitory. Catholic Charities in both Boston and Illinois have ceased to provide adoption services because their states have required them to place children with same-sex couples. And a justice for the New Mexico supreme court, after ruling that a Christian wedding photographer broke the state’s human rights act by refusing to photograph a same-sex ceremony, wrote that this Christian couple “are compelled by law to compromise the very religious beliefs that inspire their lives.” This, he said, “is the price of citizenship.” The U. S. Supreme Court refused to consider the appeal.

But combine these two issues with the decline of institutional religion and Christian nominalism, the rise of that demographic group the “nones,” the coarsening of pop culture, fresh controversies in matters of race, and the sharpening of political rhetoric in the culture war, perhaps especially in this present election, and it’s hard to feel like America is doing well.

For myself, this doesn’t feel like the America of sparklers and Thanksgiving meals and baseball games. And in the last few years, I have felt the need to renegotiate or rethink what my relationship to America is. What does is mean to love America? And I recognize that my African American brothers and sisters in Christ have had a complicated relationship with America for much longer.

FOUR PURPOSES

This 13-week course has four purposes. The first is…

- To learn how to love our nation, people-group, or tribe. Jesus commands us to love God and love our neighbor. And one way for us to do that is to work for justice in the public square. Why should Christians care about what happens in a nation’s public square? Fundamentally for the sake of love and justice. Because we love our neighbors, we want to ensure they live in a land where justice is done. And so we should work to use whatever stewardship God has given us to that end.Has he given you a vote? Love your neighbors by using it for the purposes of justice.Has he given you the ability to think carefully through complex legal arguments? Perhaps love your neighbor by using that gift as a lawyer.Different Christians have different opportunity and responsibilities for engaging the public square. I cannot tell you how engaged God would have you personally to be. I can say that God calls you to love your neighbors and that you should care about justice, each of us according to our callings and stewardships.

- To help the church and its members “obey everything Jesus has commanded,” as the Great Commission puts it. What does “rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s” mean in a twenty-first century, democratic context?

- To recognize our idols and repent of them, to see our national and party affiliations as instruments instead of as identities, and so to become more wise in the political sphere for doing justice. I do not intend, on the whole, to make constitutional or public policy prescriptions, which means I will try to stay out of party politics as much as I can. Rather, I hope to establish biblical principles that enable citizens of any nation or members of any party to see their national or party affiliation not so much as identities but as instruments. It is when a nation or party becomes your identity that you risk veering into idolatry. I most certainly won’t be offering commentary on the ongoing elections. You have plenty of other sources for that.

- To learn how to strike the balance between cynicism and utopianism. Some of us have political hopes that are nearly messianic. Whether on the political left and right, we look to the possibility of the next presidential administration, or the possibility of getting back to the Constitution, to finally deliver what this country really needs. Others of us, however, are too pessimistic about the role that government can play, and so dismiss it altogether.

It’s true that politics is something of a Sisyphean affair. You remember Sisyphus: the king in Greek mythology who was condemned by the gods to roll an immense boulder up a hill, watch it roll down, and then repeat the act for eternity. Read the book of Ecclesiastes and you will discover that any good to be accomplished will soon be undone by history. That said, forsaking the cause of good government deprives people made in God’s image of one of the greatest blessings of common grace. I have spent enough time in the formerly Soviet oppressed nations of central Asia or the nations of central America run by whimsical dictators to know how much damage bad government can do to a nation.

THE DIFFICULTY OF THIS TOPIC

Admittedly, knowing how Christians should relate to government is a difficult topic. In the twenty-first century American Christian landscape, issues like same-sex marriage and social justice broadly divide one generation as well as one ethnicity from another. Where an older generation of Christians may have fought to take back America for God, a younger generation winces with embarrassment by these Bible-in-hand incursions into the public square.

Some Christians say the church’s job is to help transform the culture, which includes working in the political sphere. Others Christians prefer to keep the church “spiritual” and out of politics. More broadly, how do we read our Bibles politically?

And what can we say about other complicated issues pertaining to matters of the environment or war and peace or ethnic inequality and racism? Christians seem to divide over how we should respond to recent reports and videos of police brutality and questions of systematic racism, and these divisions can occur along racial lines. What strikes me whenever the latest racial incident occurs—whether its Trayvon Martin or Eric Garner, Baton Rouge or St. Paul—is that the commentary typically offers two competing conceptions of justice: one concept of justcie tries to recognize the role of the group, and one gives primacy to individuals. One claims to describe larger patterns; the other claims to emphasize only the individual facts. So what exactly is justice, and how do we think about it biblically?

If we were to summarize how American Christians view the relationship between our faith and politics, we could do worse than to illustrate it as a big pot of stew. It’s a pot that has been simmering for centuries, and contains all our favorite phrases like so many potatoes, carrots, and chunks of meat: “Render to Caesar”; “be subject to the governing authorities”; “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”; “no law respecting an establishment of religion”; “wall of separation between church and state”; “of the people, by the people, for the people”; “I pledge allegiance to the flag”; “In God we trust.” The political lines of Scripture cook together with the sacred lines of American history, each flavoring the other. Add a dash of today’s pop-ideologies like political correctness and the seasoning of our favorite talking heads in the media. And what you get is political and philosophical mish mash. When a real debate arises—concerning abortion, same-sex marriage, health care, Black Lives Matter—we reach down with our soup ladle and scoop out a phrase, whichever seems most suited to the moment. Sometimes we want the government to keep its hands off; sometimes we demand it acts. Now freedom, now responsibility, now justice, now one principle, now another. Today’s hot-button issues yield tomorrow’s counter reactions. One Christian tribe might read from this political party’s script, another from that party’s. And operatives in both parties are only too happy to co-opt the God vote, but only as long as God doesn’t shape the party, but the party shapes God. In all this, it’s hard to see much consistency in how Christians approach politics.

Again, these are difficult issues. What should Christians do for government? What should Christians expect of government? As you see in the course schedule in your handout, those two questions provide the basic structure for this course.

TWO TEXTS IN MATTHEW

I want to set the stage for the course by looking at the two passages in Matthew’s gospel where Jesus refers to paying taxes.

Matthew 22

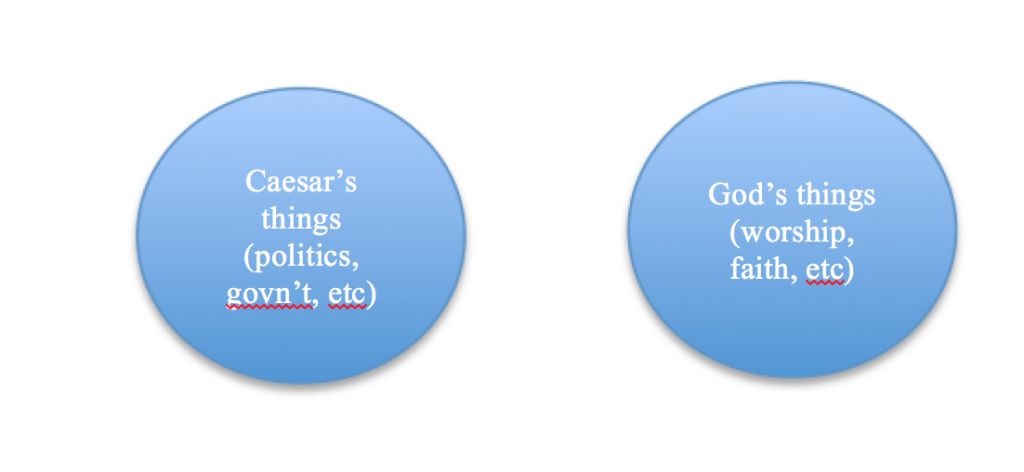

If we were to ask most American Christians what the most important Bible verse for understanding the relationship between politics and religion is, what do you think they would say? I’ve not taken a poll, but my guess is that many would point to the passage Matthew 22 where the Pharisees ask Jesus whether they should pay taxes to Caesar, whose governance over them they regarded as illegitimate. Yet Jesus asks for a denarius and asked, “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” “Casesar,” they said. Jesus then said to them, “Therefore render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Many American Christians read that and probably interpret the text something like the two circles you see in your hand out:

In many ways, this is philosophical liberalism, and the view that informs the way most Americans (Christian and non) think about politics. You have the domain of government and politics in one circle, and the domain of God and religion in another circle.

Now the fact that Jesus would say to a Jewish audience “Render to Caesar” means that obedience to Jesus will no longer require obedience to one particular nation state and its government, as had previously been the case for God’s people with Isreal. Instead, Christ’s followers are to be obedient to any and every state where they find themselves. Jesus had no intentions to establish a theonomy, that is, a state which combines church and government.

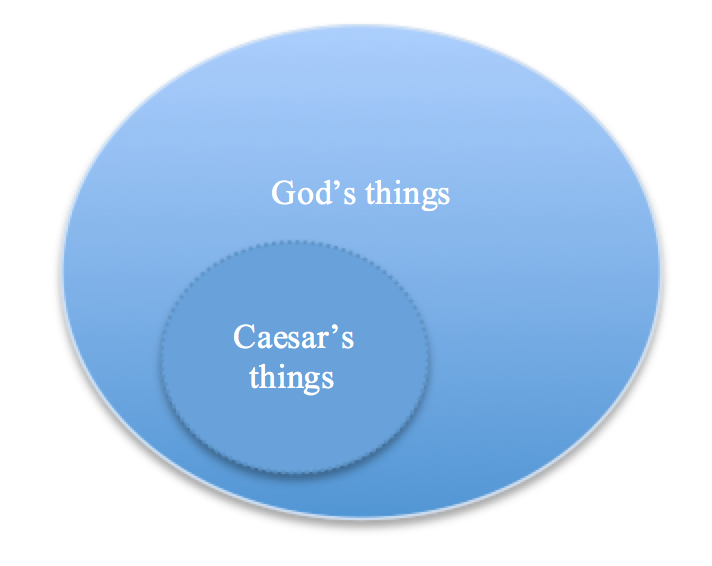

But the phrase “render to God” tells us we cannot quite separate God’s things from Caesar’s things, as the two separate circle imply. NT scholar D. A. Carson has made the observation, “When Jesus asks the question, ‘Whose image is this? And whose inscription?’ biblically informed people will remember that all human beings have been made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26). If we give back to God what has his image on it, we must all give ourselves to him. Far from privatizing God’s claim…Jesus’ famous utterance means that God always trumps Caesar.”[1] After all, Caesar himself was created in God’s image and belongs to God! Really, the picture provided by Matthew 22 is more like the big circle inside the little circle in your handout:

Jesus, we know from Matthew 28, is the authority to which all other authorities must answer. He will ultimately judge the nations and their governments. The state exists by Jesus’s permission, not the other way around, even if states don’t acknowledge this fact. “You would have no authority if it had not been given to you from above,” said Jesus to Pilate, referring to God, not Caesar (John 19:11; Rev. 1:5; 6:15–17).

Matthew 17

But there’s another text in Matthew in which Jesus refers to paying taxes. It’s both more confusing, at least at first blush, and more helpful for seeing the basic posture of Christ followers toward the government. We read beginning in verse 24:

When they came to Capernaum, the collectors of the two-drachma tax went up to Peter and said, “Does your teacher not pay the tax?” 25 He said, “Yes.” And when he came into the house, Jesus spoke to him first, saying, “What do you think, Simon? From whom do kings of the earth take toll or tax? From their sons or from others?” 26 And when he said, “From others,” Jesus said to him, “Then the sons are free. 27 However, not to give offense to them, go to the sea and cast a hook and take the first fish that comes up, and when you open its mouth you will find a shekel. Take that and give it to them for me and for yourself.”

On the one hand, Jesus avers, “the sons [of the kingdom] are free.” They are not ultimately bound by the institutional constraints of the temple complex since it would soon pass away. On the other hand, Jesus did not wish “to give offense to them” and, presumably, wanted to acknowledge that temple’s present rule was given by God and was therefore legitimate.

How do we make sense of this? What we find here is the overlap of two ages: the age of creation with its institutions, and the age of the new covenant, with its institutions. As Christians, we live in both ages simultaneously.

Let me put it like this: imagine that a new president was just elected, and he’s hired you as White House butler (is there such a thing as butlers anymore?). Suppose further it’s January, and you’re in that space of time after the election, but before the inauguration, so technically the last president and his butler are still running things in the White House. And part of the transition process involves you and your serving staff actually working for him for a month. Suppose then this soon-departing butler asks a member of your team to polish the silver in a manner that your team member thinks is outdated and not up to speed on the latest silver polishing technology. They complain to you. What do you say?

I expect and hope you’d say, “God has placed him in charge. Honor him because by doing so you show honor to what God has established. But, look, he’s out of here in a month. And in a month you’ll be able to bring all your fancy silver polishing methods to bear on the project.”

Jesus, likewise, is saying, Respect and honor the legitimate institutions of this present age. Let them do their job. BUT realize they are passing, and do not give them ultimate allegiance or hope. Think of Paul in 1 Corinthians 7: If you’re a slave he says, get your freedom if you can, but realize it’s not the end of the world if you cannot. These things are passing.

So put these two passages in Matthew together, and what can we say about our basic posture toward government? Submit to it, work for its good, but remember that it is temporary, and the eternal things must always guide our approach to the temporary things. We must always approach politics and government remembering who we are in the gospel first and foremost.

A NEW IDENTITY

I find that this second story from Matthew 17 is crucial for reminding us who we are when it comes to the topic of politics. When you become a Christian, your identity dramatically changes, and you gain a new citizenship. Suddenly, the most important thing about you is not who your parents are, where you are from, what color your skin is, your nationality, whether you are married, or anything else that humans ordinarily use to identify one another.

Who are you, Christian? You are: A son or daughter of the divine king, says Jesus. You are: A citizen of his kingdom. A new creation. Born again. An adopted heir. A member of Christ’s body, the church.

When conversion happens, then, you find yourself having to renegotiate how you relate to all those old categories. How do you relate to your parents, your colleagues, your friends, your ethnic group, your government, and the public at large?

Once upon a time, our church had an American flag perched on the platform. It was taken out during renovations to the main hall, and Pastor Dever asked for them not to be placed back in the room. When one older lady objected, he explained that, as Christians, we have more in common with our fellow Christians from Nigeria, Russia, or China than we have in common with non-Christian Americans. A gathering of the church is not an American assembly, but a Christian assembly.

The Bible calls Christians “aliens” and “strangers” and “sojourners” and “exiles,” depending on your translation. And these labels resonate with Jesus’ instruction to live in but not of the world. Knowing how to strike both sides of the “in not of” balance is challenging in every area of life, perhaps especially in our relationship with our nation generally and to the public square specifically. How do we live as citizens of a nation while being a citizen of the kingdom of Christ?

The primary goal of this is not to help Christians make an impact in the public square. It is not to help the world be something. It is to help Christians be something. My posture, you might say, is a pastor’s. I want Christ’s people to follow Christ in every area of life, including in their capacity as voters, office holders, lobbyists, editorial writers, jurists, citizens.

Now, I hope that what follows does equip some of you to make an impact in the public square, and that all of you might know what it means to live peaceful and quiet lives (1 Tim. 2:2). But honestly, you may or may not make a difference “out there.” Society may get better; it may get worse, regardless of the activities of faithful Christians. That, finally, is outside of your control and mine. What is within our control is whether or not we seek justice, love of our neighbor, and do both of these things wisely, not foolishly. On the last day, God will not ask you, “Did you produce change?” but “Did you faithfully love your neighbor and pursue justice in those places where I gave you authority?”

SERVANTS, IMPOSTERS, AND A BATTLEGROUND OF GODS

It is when we take a biblical or a God’s-eye view of politics that we discover the governments of this world must be characterized two ways simultaneously. They are both servants and imposters. They are servants because, in their created capacity, they have been instituted by God to reward good and punish bad: “for he is God’s servant for your good,” says Paul. “But if you do wrong,” Paul continues, “be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer” (Rom. 13:4).

Yet these same servants simultaneously vie for supremacy with him. They deny him. From the beginning of history, they have claimed to represent other gods, and to possess power by their own rights. “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice?” boasted the king of Egypt, prompting the Lord to pronounce in kind, “on all the gods of Egypt I will execute my judgments” (Ex. 5:2; 12:12). The governments of this world, then, are not just servants. They are imposters. Roman 13’s creation perspective must be overlaid with Psalm 2’s perspective informed by the fall: “The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the Lord and against his Anointed, saying, ‘Let us burst their bonds apart and cast away their cords from us’” (vv. 2-3).

A nation’s public square is where its political players go to wage war on behalf of their gods. It is a battleground for a nation’s gods.

So it was in ancient Greece, where Socrates, that urbane figure of philosophical lore, was executed, in Plato’s words, for “believing in deities of his own invention instead of the gods recognized by the state.”[2]

So it was in ancient Rome, whose caesars and proconsuls accused Christians of an atheistic hatred for the human race because they would not pay tribute to the Roman gods whose favor sustained the well-being and prosperity of the empire.[3]

So it was in the Bible’s chronicle of ancient Babylon, where Nebuchadnezzar required a nation to worship a golden image, to which 3 Hebrew boys responded, “we will not serve your gods or worship the golden image” (Dan. 3:18).

So it was in the state of ancient Israel itself, where the gods of Solomon’s foreign wives infiltrated not only the capitol city’s walls but the king’s innermost chambers and there curried political favor, leading a later prophet to accuse the nation of having as many gods as it had cities (Jer. 2:28; 11:13).

And so it is whenever a twenty-first century Washington DC political operative sounds the bugle, “We will deploy every tool and tactic at our disposal,” in order to fulfill whatever the political agenda of the day happens to be.[4] Yes, the language of “God” and “worship” has been largely excised from today’s civic discourse in any meaningful sense, but the holy battle rages on. All political activity is fundamentally spiritual. Behind every act of Congress, Supreme Court decision, protestors’ picket line, or social media campaign is someone’s basic worldview of how things ought to be, and behind that worldview is nothing other than a god. This is true whether the matter up for debate is abortion, same-sex marriage, tax policy, immigration law, or funding for national parks.

Essayist Mary Eberstadt captured just this idea in her article entitled, “The First Church of Secularism and its Sexual Sacraments,” when she writes,

The so-called culture war…has not been conducted by people of religious faith on one side, and people of no faith on the other. It is instead a contest of competing faiths: one in the Good Book, and the other in the more newly written figurative book of secularist orthodoxy about the sexual revolution. In sum, secularist progressivism today is less a political movement than a church….

The students at Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989 affirmed the same thing, albeit unconsciously, when they sang the old socialist song The Internationale, “We want neither gods nor emperors.” A biblical translation might read, we would be our own gods.

Richard John Neuhaus famously argued that we must not leave the public square “naked,” by which he meant bare of religious speech. I would go one step further and argue that it is impossible for it to be so.

Our gods determine our morality, and they determine our politics—unavoidably. In this battleground of gods called the public square, no one god wins all the wars, and so a nation’s laws are an amalgam of competing values and commitments, peace-treaties and détentes, cobbled together over time by compromise and negotiation.

Does that mean there’s no such thing as religious liberty, and no separation of church and state? In fact, Christianity is one of the few belief systems that doesn’t seek to impose it’s worship on others because (i) it knows it cannot, (ii) God has not authorized us to do so, and (iii) it possesses a doctrine of the church, which the Bible keeps separate from the state. But if your religion has no church, where will you look in society to do the work of the church—that is, to teach, disciple, and even discipline for right “doctrine”? If you happen to be politically motivated, you will look to the state, whether through the schools, the legislatures, or the courts. Back to Eberstadt’s point, does secular progressivism not view the government as the church, responsible to ensure we all think the same way? We’ll return to church and state in future weeks.

CONCLUSION

I started on an American note. Let me conclude there. Lots of writers today say that we need to go back to the American founding to re-embrace those principles. I’m not sure we have ever left them. Instead, we are discovering what people like John Adams and George Washington warned would happen should our system of government be inhabited by people without virtue or morality.

What’s called the American Experiment is the idea that a group of people from a multitude of faiths or no faith could come together and establish a just nation on a set of universally agreeable principle like “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” We don’t agree on who God is? That’s fine. We agree on the dignity of the individual and the freedom of conscience. Can we shake hands on that? And so colonial Baptists like Isaac Backus and John Leland shake hands with liberty-loving deists like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. But what happens when my conscience tells me that I can abort my baby, or that I can marry someone of my own gender? Why should your conscience trump mine?

Could it be that what we really loved about the American system of government is that it made a suitable home for our Christian values? But now the values of another religion, something more akin to paganism, have made their home in our house. Meanwhile, we get the dirty looks that houseguests who have overstayed their welcome receive. Maybe God’s purpose in all of this is to teach us that this country was never our home after all, for as much as it’s good to give thanks with sweet potato casserole. If Christians in America have been pushing the rock up the hill for a couple centuries, these days we get to watch it roll back down.

But that’s okay. The sons and daughters of Christ’s kingdom are free, said Jesus, because our kingdom comes from another place. This is not our home. However, not to give offense to them, we render to Caesar what is Caesar’s. God established Caesar to do good, and in the United States Caesar remains “We the people.” And loving your nation, people-group, or tribe, whether in America or anywhere else, means we work for the good and justice of others, whether sitting in the living room or left out on the porch, whether second to Pharaoh like Joseph or imprisoned in a lion’s den like Daniel.

* * * * *

Editor’s note: For a fuller description of Jonathan’s views on church and state, seePolitical Church: The Local Assembly as Embassy of Christ’s Rule (IVP, 2016).

FOOTNOTES:

[1] In D. A. Carson, Christ and Culture Revisited (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 57.

[2] In Apology, translated by Hugh Tredennick, in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961), 24b; 24-27.

[3] See Tacitus, Annals, book xv, chapter 44. See also the comments of Porphyry in Robert Louis Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (Yale 156.

[4] Quote in Byron York, Washington Examiner, “The guns of August: Left and Right go to ward over Obamacare,” August 1, 2013, posted at http://m.washingtonexaminer.com/the-guns-of-august-left-and-right-go-to-war-over-obamacare/article/2533794. Accessed August 5, 2013.