What Authority Has God Given to Governments?

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt from Jonathan Leeman’s forthcoming book ‘Authority: How Godly Rule Protects the Vulnerable, Strengthens Communities, and Promotes Human Flourishing‘, published with permission from Crossway.

The government’s job description: To administer the justice requisite for protecting human life, secure the conditions necessary for fulfilling the dominion mandate, and provide a platform for God’s people to declare God’s perfect judgment and salvation.

Some governments are better, and some are worse. So says the Bible. The Pharaoh of Joseph’s day was better; the Pharaoh of Moses’s day was worse.

Governments are God’s servants, one passage tells us (Rom. 13:1–7). Yet they’re also imposters, says another, because they rage and take their stands against God and his messiah (Ps. 2:1–3).

So, what makes a good government good? A good government provides a basic protective justice for all its citizens, including God’s people, whether it recognizes them as God’s people or not. (Think of Cyrus sending the Jews back from exile.) That means Christians should care about good government both for their neighbor’s sake and for the church’s sake.

With the other offices we’re discussing in part IV, the focus is on your individual authority—as with a husband, a parent, a manager, or an elder. Yet government and church are a little different, because we’re thinking about exercising authority in a group where we may or may not have much influence and where our individual voice may or may not reflect the group voice. This is especially true of the government. The “government” might be one person—the king. Or it might entail “We the people” of the nation. Government is even more difficult because we must deal with the church-world relationship, and Christians disagree about the nature of that relationship. Consider three models. Someone could say that Christians . . .

(1) should seek to enforce Christianity through the government;

(2) should seek to enforce aspects of Christianity through the government, namely, a number of its moral standards;

(3) should not seek to enforce Christianity through the government at all, but should express their faith entirely in the private sphere.

I assume that options (1) and (3), as stated here, don’t sit quite right with any reader. Yet people do lean toward one or the other. The (1)-leaning people feel the weight of God’s Lordship and judgment over all things, and they point to the Ten Commandments. The (3)-leaning recognizes that we cannot force our faith on people, and they point to Jesus’s instructions about rendering to Caesar what’s Caesar’s and God what’s God’s (Matt. 22:21). Still, most of us, including myself, don’t feel like we can move all the way to position (1) or position (3), but put ourselves somewhere in the middle.

Through the centuries, Christians in this middle lane have tried different ways to explain why we can open our Bibles and seek to impose with the sword a verse like “You shall not murder” on unbelievers but not one like “Jesus is Lord.” That’s when they start talking about things like Augustine’s two cities, or some version of Martin Luther’s two kingdoms, or Reformed views on the spirituality of the church, or Baptist views on religious freedom, or even John Locke’s distinction between the inner and outer person in his Letter concerning Toleration. Whether or not you’re familiar with any of these specific viewpoints, where would you place yourself on the spectrum between (1) and (3)?

My goal in this chapter is to answer the questions about authority that we’ve been considering in part IV, in a way that leads to position (2) as related to governmental authority. This means that, contrary to position (1), I believe we should affirm the separation of church and state, or at least a version of it. Yet contrary to position (3), I don’t believe we should affirm the separation of religion and politics. That prospect, I’ll argue, is impossible. Yet all these additional complexities make this the longest and most dense chapter in the book. Buyer beware!

What Is the Civil Government’s Authority?

In the first instance, governmental authority is a necessary entailment of the dominion mandate that God gave to Adam and Eve (“be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it”). It’s a condition of expanding our presence on the planet with other people, so that we might live together in an orderly, predictable, and cooperative fashion. Even in an unfallen world, someone needs to decide whether we drive on the right side of the road or the left.

Yet governmental authority after the fall must also deal with sinful agents and the scarcity of resources. That means governmental authority must recognize that God does indeed command all human beings to fill the earth and subdue it, but also that these humans are now murdering each other (Gen. 4:8), stealing one another’s provisions (Gen. 14:11), lying to their husbands and fathers (Gen. 27:13, 19), raping one another’s daughters, and slaughtering entire cities in retaliation (Gen. 34).

For this reason, God introduces the authority to use coercive force. Nothing in the original dominion mandate says that one human being has the right to arbitrarily use force over another human being. The natural law doesn’t say that either (I don’t believe). After all, every human shares equally in creation in our God-assigned authority. Therefore, God must specially authorize the use of coercive force, which brings us to what we might call the “Great Commission” text for governmental authority on this side of the fall: Genesis 9:5–6. Just like Matthew 28 does for churches, Genesis 9:5–6 doesn’t spell out everything a government will need to do, but it lays down a few basic constitutional principles.

Let’s start with this phrase: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.” You may not have spent a lot of time meditating on that verse, but it’s worth pulling up a chair and staring at it for a moment. It packs quite a punch. First, it authorizes the use of coercive force in order to prosecute the taking of life. By implication it also authorizes a government to prevent the unjust taking of life. For instance, I’d say it gives a government moral permission to say, “Here’s the speed limit,” or “Commercial aircraft must meet these safety codes” (see Deut. 22:8), or even “Pay taxes so that we can build an army for our nation’s protection” (see Luke 3:13; Rom. 13:7).

Second, this verse establishes a principle of due process: parity. The punishment must fit the crime. It’s life for life, not life for stealing a horse, like the fifty-one recorded instances of people being hanged for horse stealing in early America, the last one in 1851.[1] The punishment should always fit the crime—“eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth,” as a later passage puts it (Ex. 21:23). People are sometimes scandalized by this principle (called lex talionis), but keep in mind that, in the ancient world, this principle typically served to limit the otherwise unconstrained demands for vengeance. Think again of Jacob’s sons massacring a city in retaliation for the rape of their sister Dinah (Gen. 34).

Not only that; under-punishing a crime risks devaluing the worth of the victim. It says the life that was murdered or the goods that were stolen weren’t worth much, like offering you a stick of gum to compensate for your stolen diamond ring.

The affirmation of parity also implies that every governmental action requires a just measurement. “A just balance and scales are the Lord’s; all the weights in the bag are his work. It is an abomination to kings to do evil, for the throne is established by righteousness” (Prov. 16:10–12). Practically, for instance, a government must not bribe or overtax its citizens for selfish gain (see Prov. 29:4 ESV mg.). Any tax requires a clear and just gauge that accords with government’s basic life-protecting purposes.

Third, Genesis 9:6 affirms the value of every human life as made in God’s image and therefore equally valuable. People of every color and creed, men and women, deserve to be treated as God-imagers and possessors of a basic political equality. Jim Crow laws that read “separate, but equal,” pushing blacks to different drinking fountains, are unjust.

Fourth, the verse subjects every human to its requirements, including governments themselves. Look again at the first word of verse 6: “whoever” wrongly sheds blood. The verse becomes a boomerang whenever governments use their authority unjustly. It indicts the murderous dictator and the racist town sheriff alike. No government can claim to be “above” its reach. It keeps governments and citizens alike accountable.

Fifth, this verse possesses a theological basis—“for God made man in his own image”—but it doesn’t authorize us to enforce that basis. The trigger for action is harm to humans—“blood”—not harm to God. After all, how do you measure or establish parity for an offense against God, to say nothing of the fact that we cannot harm him. As such, the verse doesn’t authorize us to prosecute crimes against God, like blasphemy or idolatry, if there is no quantifiable harm done to a human person. It leaves open a space for religious freedom, and that space is anything outside of the government’s jurisdiction. On the flip side, however, the verse doesn’t allow someone to claim “freedom of religion!” if their religion causes actual harm, like a Christian Scientist who wants to deny medical care to a child whose life is medically threatened.

As I said, there’s a lot of punch packed into this one little passage which applies to all humanity, every son and daughter of Noah, and not just to God’s special people. As you can see with several of the citations above, I’m reading this passage with later biblical texts in mind. And I’ll cite more throughout this chapter.

There is one more thing to notice about verses 5 and 6 of Genesis 9: they are set inside a paragraph bookended with the command to “Be fruitful and multiply” (vv. 1, 7). What does that tell us? The authority to use coercive force facilitates the larger goal of enabling people to fulfill the dominion mandate.

Governments exist, then, to help secure the basic conditions necessary for fulfilling the dominion mandate. For starters, that means governments should protect the basic structures of marriage and the family, so that people can indeed “be fruitful and multiply.” Governments should not redefine marriage to include homosexuals, because (i) governments don’t have the authority to do so; (ii) they weaken real marriage by defining marriage around the feelings of the couple rather than their potential for fruitfulness; (iii) and the redefinition denies children the right to a mother or father. In a sense, they steal a mother or father away from a child. The children are victims.

One might envision many other factors that hinder the work of fruitfulness, dominion, and the basic God-imaging political equality required for fruitfulness and dominion. The oppression of ethnic minorities hinders it. So do entrenched cycles of poverty. That doesn’t mean the government must ensure every citizen possesses the same economic starting point. But I can imagine a Christian arguing that a basic economic safety net—enough to wake up with a roof over your head, eat, and get to work in the morning—serves the purposes of dominion. As King Lemuel’s mother says to him, “Open your mouth for the mute, for the rights of all who are destitute. Open your mouth, judge righteously, defend the rights of the poor and needy” (Prov. 31:8–9; also, 29:14).

A Christian might also argue that facilitating the dominion mandate includes a good monetary policy. Such a policy provides both a stable currency and standardized interest rates. A stable currency protects everyone’s wealth and livelihood, and standardized interest rates prevent usury and the exploitation of the poor (see Ex. 22:25; Prov. 22:7; 28:8; Matt. 25:27). Jesus himself affirmed that a coin printed with Caesar’s image legitimately fell within Caesar’s jurisdiction: “Render to Caesar what belongs to Caesar” (see Matt. 22:21).

Yet whether or not monetary policy or a welfare policy or any other policies we might think of are reasonable deductions to draw out of the relationship between Genesis 9:6 and the bookended verses 1 and 7 (“Be fruitful and multiply”), the Scriptural baseline is that God grants human beings the authority to form governments that protect our lives and promote the conditions necessary for fulfilling the dominion mandate. That’s why Paul tells us to pray “for kings and all who are in high positions, that we may lead a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way” (1 Tim. 2:2–3).

What Kind of Authority Is Governmental Authority?

Clearly, governmental authority is a coercive authority, and it’s an authority of command, as defined in chapter 11. But it is also a divinely ordained means of justice. All people are made in God’s image and therefore deserve righteous treatment. Government serves the ends of justice by protecting these God-imagers.

“By justice a king builds up the land,” says Proverbs (29:4). King David’s throne, therefore, existed for the sake of upholding justice: “So David reigned over all Israel. And David administered justice and equity [righteousness] to all his people” (2 Sam. 8:15).

What is justice in the Bible? People often define justice as giving people their due. That’s not a bad definition. It gets us part of the way there. Yet I think we do slightly better by putting God’s law front and central in our definition as well as by observing that the Hebrew word for “justice” is the noun form of the verb “to judge.” Biblical justice, I’d say, is making judgments in accordance with God’s standards of righteousness.

Think of Solomon standing in front of two prostitutes, both of whom claimed a baby was hers. Solomon’s task in that moment was to render a righteous judgment—and so do justice. Gratefully, he did: “And all Israel heard of the judgment that the king had rendered, and they stood in awe of the king, because they perceived that the wisdom of God was in him to do justice” (1 Kings 3:28). Justice depends on a judgment, but that judgment needs a standard, a ruler or scale by which to measure the judgment. The right standard is the law of God’s righteousness. Not surprisingly, the Bible says of God’s own government, “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of your throne” (Ps. 89:14).

To translate this into an American setting, we can say that all three branches of government should do justice—render righteous judgments—each in its own way. The legislator should pass just laws. The executive branch should enforce just laws in a just way. And judges should uphold just laws and overturn unjust ones. In each case, their work of justice should not be defined by some other god’s version of righteousness, but by God’s definition of righteousness.

Many Westerners assume otherwise. Our nations are pluralistic, we reason. People believe in many different gods, from the big-G Gods of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, or Mormonism, to the little-g neo-pagan gods of sex, body worship, consumption, and identity politics. Therefore, Christians who lean toward position (3) at the beginning of this chapter say we need to create a public square and establish rules of justice that are neutral between people’s competing gods. And we can do that by defining justice as “protecting people’s rights.”

That solution to societal pluralism is not entirely wrong. But it’s like picking the fruit without attending to the root. Justice does include protecting people’s rights. The trouble is, it’s a society’s reigning gods that will define which rights are right. Shall we affirm the right to an abortion, the right to same-sex marriage, the right to define our own gender as children apart from parental intervention?

It’s true that justice entails protecting people’s rights. I’d agree with those who argue that the fact that we are created in God’s image is the foundation for human rights.[2] Returning to our meditation on Genesis 9:5–6, we might say that it grants us the right to life, the right to be treated by our government with equal dignity, the right to worship God free from coercion, the right to insist on a fair trial and due process, even the right to all the liberties requisite for fulfilling the dominion mandate. Still, we possess these rights not because they are inherent in us apart from God, but because God says they are right. Rights are right only when and where God says they’re right. Right is the root of justice, rights are the fruit. Pay attention to the “s.” And the government’s job begins with what’s right (see Rom. 13:3–4; 1 Pet. 2:14).

Group (3) and others will quickly reply, “But whose definition of “right” shall we legislate? Which God or god’s?” They ask the question as if anyone has ever abandoned his god when stepping into the public square. In fact, no one ever does or can. We all argue on behalf of our God or gods in the public square and try to win a majority of the votes. Everyone. It’s impossible to do otherwise. In the ballot box or on the Senate floor, you fight for what you most value and worship. Inevitably. The real question is, who, whether by hook or by crook, wins any given debate, election, or war?

Why Government Authority?

Why does God give authority to the government? We’ve already considered the first two reasons the Bible provides: to protect life and to secure the conditions of the dominion mandate and human flourishing. A government does these two things by administering justice. Call all this the proximate or immediate purposes of government. These purposes are concerned with temporal things.

Yet the government’s temporal concerns ultimately serve an eternal purpose: setting the stage for God’s work of redemption. You might think of guardrails on a mountain road. Their proximate or immediate purpose is to keep cars on the road. Their ultimate purpose is to help cars get from City A to City B.

This is the real story behind the story of governments in the Bible. The spiritual forces of hell fight to use governments to devour God’s people—from Moses’s Pharaoh, to the Assyrian Sennacherib, to the Roman Pilate, to the raging nations of Psalm 2, to the beasts in Revelation 13, depending on how you read Revelation. Meanwhile, God raises up particular leaders to protect and shelter his people—from Joseph’s Pharaoh, to the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar after his humbling, to the Persian Cyrus, to the Roman Festus. God’s ultimate purpose for government is not merely to keep people alive but to keep them alive so that they might know God. Genesis 9 comes before Genesis 12 and the call of Abraham for a reason. Government provides a platform on which God’s redemptive drama can play out. Common grace sets the stage for special grace, like teaching people to read so that they can read the Bible.

Two New Testament texts make this connection crystal clear. First, look at the quote from Acts 17 at the beginning of this chapter. It says that God determines the borders of nations and the dates of their duration so that people might seek him (Acts 17:26–27). Our nations and governments help to keep us alive. Why? “So that,” Paul says, people can find their way to God. Governments don’t bring us to God, but they free us up to seek him.

Now look at 1 Timothy 2. Paul urges us to pray for kings and all in high positions so that we may lead “peaceful and quiet lives, godly and dignified in every way” (v. 2). Fair enough. We want governments that clear the ground for us to live such lives, lives where we can live out the full range of godliness that God intends. Yet is that all there is to say? No. Paul then tells us why we should pray for governments to do this: “This is good, and it is pleasing in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim. 2:4). The two steps in these verses are interesting. Step one: don’t pray that governments would work to make disciples but that they would work for peace and safety. Step two: realize that this is important because God wants people to be saved, which apparently is work that belongs to the institution that the rest of 1 Timothy is about: the church. The government’s job is to clear the path, smooth the road, set the stage, build a platform. A clear path and smooth road pleases God and should please us—for salvation’s sake.

In short, we don’t want a government that thinks it can offer redemption, but one that views its works as setting the stage for redemption. It builds the streets so that you can drive to church; protects the womb so that you can live and hear the gospel; protects the currency so that you can make an honest living and give to missions; insists on fair-lending and housing practices so that you can own a home and offer hospitality to non-Christians; protects marriage and the family by not redefining marriage and by kicking strip clubs out of the city so that husbands and wives can better model Christ’s love for the church.

Whom should you vote for in the next election? Vote for the party or candidate that seeks to do all that.

What Are the Limits of the Government’s Authority?

If a government’s job is not to make disciples but to set the stage for disciple making, we need to think about its limits, as well as whether models (1), (2), or (3) from the beginning of this chapter are best. What are the limits of a civil government’s authority?

The first and most crucial limit is, no government should regard itself as God. When the individual officers comprising the government don’t acknowledge God, they will either worship another God or regard themselves as God. Members of group (3), insofar as they are tempted to believe governments can remain neutral between the gods, may need to be reminded of this point. Every prince and member of parliament, voter and judge, should acknowledge God and recognize that he or she is under God:

Now therefore, O kings, be wise;

be warned, O rulers of the earth.

Serve the Lord with fear,

and rejoice with trembling.

Kiss the Son,

lest he be angry, and you perish in the way,

for his wrath is quickly kindled. (Ps. 2:10–12; see also Ps. 82:7)

I’m not saying a person has the right to use the power of government to require another human being to acknowledge God. A moral “is” does not make for a sword-wielding “ought.”[3] I’m simply saying that, before God himself, everyone working in government should acknowledge and submit to God—“lest he be angry.” Remember the principle from chapter 6: good authority is not unaccountable, but submits to a higher authority. That applies to governments, too.

A government of people who refuse to acknowledge the true God of the Bible is a government that has supplanted him. Such governments may, by God’s common grace, do justice for a season. But eventually they will turn beastly. As examples, think of Moses’s Pharaoh: “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice” (Ex. 5:2). Or the Assyrian Sennacherib’s lieutenant: “Do not let Hezekiah make you trust in the Lord by saying, “The Lord will surely deliver us” (Isa. 36:15). So with the communist and fascist regimes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Or the Mongol empire of the fourteenth-century Muslim Tamerlane. Or the many indigenous civilizations, like the Aztecs, who sacrificed countless people to their gods.[4] Or so many more.

That said, members of governments might acknowledge God with their lips (see Isa. 29:13), explicitly calling themselves “Christian,” yet still perpetrate grave injustices by failing to acknowledge the image of God in their subjects. Throughout the Middle Ages the Christian monarchs of Europe were violently and grotesquely anti-Semitic. Those same governments, as well as the governments of the New World, supported racial slavery, even when their founding documents acknowledged God. The Dutch Reformed government of South Africa, also, devised the doctrine and practice of apartheid. So-called “Christian” governments can turn beastly, too.

In short, creatures who deny the Creator revealed in the Bible, or his image in every individual, will eventually use governments to kill and exploit one another. It’s easy math: creature – creator + government = terrible injustices. I believe this is why God determines not merely the boundaries of nations, but their “allotted periods” or duration (Acts 17:26). By his common grace he employs a nation and its government for a season to do their work, yet eventually their denial of him leads to injustices that require their removal. This is the biblical story of nation after nation outside of Israel (e.g., Gen. 15:16; Isa. 10:5ff.; Hab. 2:2–20).

In speaking of acknowledgment, I’m not arguing that we need to put Jesus’s name into our constitutions, just like I wouldn’t argue that we need to put his name into home mortgage or auto loan contracts. I’m not going to insist that the non-Christian officers at a bank, in giving me a loan, put words into the contract that they personally disavow. My simple point for now is, the heart of every voter and president on earth, like the heart of every lender and borrower signing loan papers, should acknowledge and submit to God. “By me kings reign,” says Lady Wisdom, “and rulers decree what is just” (Prov. 8:15). And where does wisdom begin but with the fear of the Lord.

The government’s second limit concerns the threat of its infringing unjustly into the parental sphere. This is a complicated topic, because God surely intends for governments to protect abused or abandoned children. We considered this in chapter 5. Foster and child protective services I regard as a hypothetically good thing. Not only that, but the government also seems to have a legitimate interest in ensuring that its citizens are literate in math, reading, science, and more. Nations with high literacy rates flourish more than those with low literacy.

Yet if education policy inferentially falls within the government’s domain, biblically speaking, it explicitly falls within the parents’ domain, as we considered in the last chapter (see Proverbs). A good government, therefore, will respect the authority of good parents to educate their children. It may educate children or offer standards for education where necessary. And it will protect children against negligent or incompetent parents. Balancing these different objectives, no doubt, requires the wisdom of Solomon.

Meanwhile, a bad government forsakes wisdom and will eventually usurp the authority of good and bad parents alike.

It’s worth observing, therefore, that so many of the church versus state controversies of the last hundred years have occurred in a domain that fundamentally should belong to parents—education. Think, for instance, of the controversies surrounding prayer in public schools, whether tax dollars can assist parochial schools, or what’s taught about evolution or sexuality in the classroom. Christians treat these as church/state or religious freedom issues, when really the trouble began upstream when parents let themselves become dependent on the state, ceding sovereignty to it, to educate their children. To be sure, we would need to radically reimagine the last two centuries of economic, industrial, and civic development in society as a whole in order to envision a nation where parents take responsibility for educating their kids, perhaps with government facilitating, not owning, that education. My point is not to say there are easy solutions here. It’s merely to describe the landscape: the Bible gives primary responsibility to educate the child to parents, and when we hand that off to the state, we can expect further jurisdictional problems to occur, like fights over religion.

The government’s third limit, which we will think about at considerably greater length, concerns the church and religion. These comments are offered for anyone leaning toward group (1) (government should enforce Christianity), but hopefully they will help all of us better grasp what the separation of church and state means and doesn’t mean. Does the New Testament leave room for the government to criminalize false religions? Or to incentivize and sanction true religion? Does it leave room for officially established churches, or for calling a nation “Christian”?[5] No doubt, doing either curtails religious liberty.

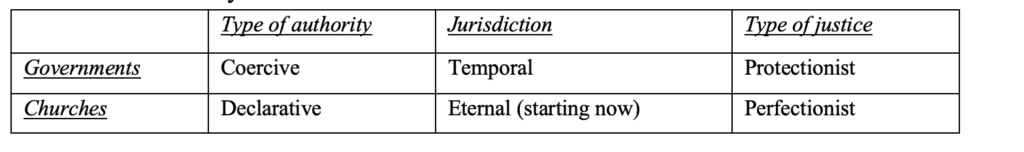

The key word, once again, is jurisdiction, and the key jurisdictional division worth paying attention to is temporal versus eternal, as well as protection versus perfection.

Ever since the days of Noah, we have seen God has assigned the governments of the nations the task of working for justice in temporal matters. Their judgments, ideally, possess an eternal purpose—they enable and don’t hinder the work of the church. And those judgments possess an eternal theological basis—that humans are created in God’s image. Still, their judgments offer merely a temporal reach—for this life only. A government can protect lives and work to ensure that the basic conditions are in place for people to fulfill the dominion mandate. But a government’s work does not go beyond death. Its sword cannot reach into eternity (Matt. 10:28; Rom. 8:35). Its impact is temporary, which is one reason Christians never need to fear unjust governments.

The government’s jurisdiction, therefore, must be limited to its actual reach.

That means, we should ask our governments to work for a protectionist version of justice. We should ask our churches, on the other hand, to declare and bind its membership by a perfectionist version of justice. If the state possesses the power of the sword, the church possesses the power of the keys to declare who God is, what he’s done in the gospel, and everything he requires of his people. The keys of the kingdom, which we’ll think about more in chapter 16, are the authority for a church to say who their members are and aren’t, through the ordinances.

Table 14.1: Authority: Governments versus Churches

The criteria for a perfectionist version of justice is perfection: “You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). The criteria for a protectionist version of justice concerns how you conduct yourself with other human beings—your neighbors: Do you give other people their due? Do you treat them fairly? Or do you harm them, exploit them, steal from them, and so forth? Do you love them as yourself? Furthermore, do you show respect and honor to the government? Do you pay your taxes so that they can do their God-assigned work?

It’s these types of temporal concerns that occupy both Paul and Peter in their most extensive treatments of governments. If you glance at the quotes from Romans 13:3–4 and 1 Peter 2:14 at the beginning of this chapter, you’ll see that each affirmed that God has instituted governments to reward the good and punish the bad. Does this mean that Paul and Peter intend for governments to punish every conceivable bad and to reward every conceivable good? Presumably not, unless we assume they intended for government to play God, who alone can judge all goods and all bads. Paul and Peter have a subset of goods and bads in mind.

What is that subset? Both apostles refer to the “approval” or “praise” of their pagan rulers. Pagan rulers wouldn’t praise those who worship and obey Jesus. They would praise those who fulfill the temporally concerned matters that Paul mentions in his summary verse 7—paying “taxes” and “revenue”[6] and affording “respect” and “honor” to Roman officials (Rom. 13:7; also 1 Pet. 2:17). Furthermore, Paul’s word for the “good conduct” that receives the king’s approval is used elsewhere for practical acts of mercy for those in need (e.g., Acts 9:36; 1 Tim. 2:10; 5:10). In short, the goods and bads that Paul and Peter have in mind are the temporally concerned matters that will draw the attention of every government, whether for godly purposes or for self-interested ones, simply by virtue of the temporal tool it has—the sword.

Reacting to the broader culture’s push against Christian convictions on marriage, sex, and gender, a growing number of Christians in recent years have begun asking whether God does in fact authorize governments to concern themselves not just with temporal matters but with eternal ones. Should we try to merge church and state, whether partially or completely? If the leaders are Christian, can the government promote or even enforce Christianity? Ever since the Roman emperor Constantine became a Christian in the early 300s, many Christians have believed so. Nations and empires even began to call themselves “Christian.” There are lighter and heavier versions of an established church or state enforcement. Or think of a dimmer switch. You can turn it on just barely, with things like Sabbath laws or using religious language in courtroom oaths. You can turn the switch up with doctrinal tests for office or tax support for clergy of a particular denomination. You can turn it up all the way by criminalizing false worship or blasphemy, even executing blasphemers, as Calvin famously supported for the Trinity-denying Michael Servetus.

To make this case, Christians typically appeal to the Old Testament kings of Israel, the Ten Commandments, or some other argument from the Mosaic covenant to argue for the fusion of church and state. But is this a legitimate appeal? I can’t address every click on the dimmer switch here. But if we’re talking about turning the switch all the way up, the short answer is no. The Mosaic covenant was given to Old Testament Israel. It does not license the governments of the nations to enforce Christian convictions about eternity, like the first two commandments in the Ten Commandments.

It’s true that every individual in government, standing before God, should acknowledge him. But just because a government is accountable to God for every action it takes doesn’t mean the government has the authority to force you to believe in God. As I said, the government’s jurisdiction should be limited to its actual reach, and a moral “is” does not make for a sword-wielding “ought.”

Yet let’s put Old Testament Israel in context. God had unique and priestly purposes for Israel. He called them to be a “royal priesthood” (Ex. 19:6). What does a priesthood do? They mediate God’s law and God’s presence. Israel’s job as a nation was to mediate God’s law and presence to the nations by obeying his law and worshiping him (see Deut. 4:6–8). For that reason, God placed his name on Israel: “You are my people, and I am your God” (see Ex. 6:7). Tragically, Israel failed to do its job, and so God cast them out of the land.

Now, think: who has the priestly job in the New Testament? That is, who is to mediate God’s law and presence and on whom does he place his name? The first word out of your mouth had better be Jesus! Okay, but who else? It’s everyone who is united to Jesus by the new covenant of his blood. The church is now God’s “royal priesthood” (1 Pet. 2:9). Sure enough, he places his name on the church. We’re baptized into his name, and we gather in his name (Matt. 18:20; 28:19). Do a word search on “name” in the book of Acts, and you’ll see the extraordinary care the apostles take on who bears Christ’s “name.”

In other words, this priestly job of bearing Christ’s name and mediating his presence to the world doesn’t go to a nation or empire. No, it passes to everyone united to Christ, the church, which is comprised of a people from every nation. To call a nation a Christian nation today or to seek to enforce the first two commandments is to go backwards to the old covenant. It’s to declare a nation priestly. Yet God doesn’t call nations and their governments to patrol the borders of who believes in him and who doesn’t, like Israel did. He calls the church to patrol those borders through its membership. We are the “holy nation” now (1 Peter 2:9). That’s why pre-conversion Paul sought to leverage the power of the sword and put people to death for blasphemy (Acts 26:10–11), while post-conversion Paul sought to leverage the power of the keys not to execute but to excommunicate blasphemers—so that they could repent and be saved (1 Tim. 1:20).

The government’s job between the Old Testament and New does not change. From the Noahic covenant in Genesis 9 to today, God has called the governments of the nations to implement a protectionist form of justice. The government’s job between the Mosaic covenant and the new, however, did change. Those priestly responsibilities which uniquely belonged to Israel’s civil order have passed on to the church.

Besides all this, think about the Noahic covenant one more time. God promised not to destroy humanity for an indefinite season, in spite of our false worship. To criminalize false worship and idolatry would seem to defy God’s own promise to withhold his judgment.

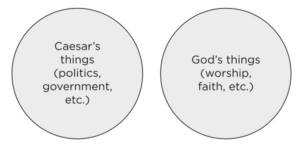

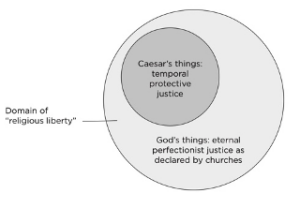

So how do we put all this together, and how do we decide between options (1), (2), and (3) at the beginning of this chapter? Consider Jesus’s words, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and unto God what is God’s” (see Matt. 22:21). I can imagine three different ways of picturing this verse, two wrong and one right. Some might say that Jesus intended to separate Caesar’s things and God’s things entirely, like this:

God versus Caesar: Option (1)

Group (3) above can tend to err in this direction, and I would call it a biblical error. After all, everything that belongs to Caesar also belongs to God. Caesar is made in God’s image. He is accountable to God. God’s coming judgment applies to Caesar and to every human government. When you, I, or Caesar step into the public square, we will represent some god and some god’s version of justice, as I said above. It’s only a question of whose. Insofar as Christians have a voice in government, whether as voters, officeholders, or anything else, they should seek to represent the true God alone. They should seek to influence others and pass laws in keeping with a biblical understanding of righteousness and justice.

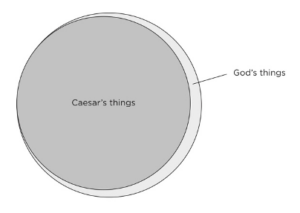

But none of this means that the Bible calls Christians to criminalize all sin, enforce all worship, renounce religious liberty, and build a theocracy, which would be another wrong way of interpreting Jesus’s words about God and Caesar. Suppose someone argued that Caesar should, if he can, promote all or nearly all of God’s things, like this:

God versus Caesar: Option (2)

Group (1) tends in this direction. Yet that would seem to be a strange interpretation of what Jesus said. It’s true that everything that belongs to Caesar belongs to God, but hardly everything that belongs to God also belongs to Caesar.

The key word, once again, is jurisdiction. Caesar, I’ve argued, has a temporal jurisdiction for implementing a protectionist justice. That’s an important circle. But when you compare that to God’s justice, which is eternal and perfectionistic, it’s hardly most of the circle. Churches should speak for the whole circle. And that’s a lot of circle that the government doesn’t need to enforce, including eternal decisions about who God is. In fact, everything outside the government’s jurisdiction we can also call the domain of religious liberty.

The jurisdictional picture that the Bible has assigned to every nation since the Noahic covenant, except for ancient Israel, looks more like this:

God versus Caesar: Option (3)

Notice that everything Caesar does is contained inside God’s circle. Which means you could, if you wanted, call everything that Caesar does “religious,” because it’s under God, whether he acknowledges God or not. I’d even say we cannot separate the political and the religious. I would say, however, the Bible insists that we separate church and state in this sense: One has the sword; one has the keys of the kingdom. Also, one has a temporal jurisdiction and is charged with enforcing protectionist justice; the other has eternal jurisdiction and is charged with enforcing perfectionist justice. In other words, the separation of religion and politics is not the same thing as the separation of church and state. The first is impossible because your religion always determines your politics, while the second is a jurisdictional assignment. Few people today seem to understand this distinction.

Perhaps an analogy would help for filling out the illustration for position (2) above. You might say that the Bible approaches governments like parents do a babysitter. “You’re not responsible to teach our kids to love and obey us,” they instruct the sitter. “You just need to keep them fed and safe, and prevent them from fighting.” The babysitter is entirely “under” the parents, but the sitter’s jurisdiction is limited. The babysitter knows the parents’ return is imminent and will seek to fulfill the parent’s will. Still, the babysitter has been given a modest job: “Your job isn’t to teach the kids to love us or worship God. Just help them play well together and go to bed on time.” Likewise, a good government will fear and acknowledge God. It knows a day is coming when “the kings of the earth and the great ones and the generals and the rich and the powerful, and everyone, slave and free” will experience God’s judgment for how they did their jobs (Rev. 6:15). Still, God has given the government a comparatively modest job.

One additional reason to keep that job modest is that, unlike most babysitters, most governments oppose God (Ps. 2:1–3). Do you really think it would be wise to give God-opposers and haters the authority of the sword over worship?

In short, the separation of church and state does not prevent us from enforcing certain Christian moral convictions in the public square; but it does mean we seek to enforce only those convictions that God authorizes governments to enforce.

So, should we use the sword to insist that murder is wrong? Yes.

That marriage is between a man and a woman? Yes.

That Jesus is Lord? Every member of government should acknowledge as much, and individuals in government that don’t will eventually veer toward injustice in their jobs, but no, we cannot force them to do so.

Finally, everything outside the government’s jurisdiction belongs to the domain of what people have long called religious liberty.

How Do Citizens Get to Work?

In short, good governments don’t try to usher in Christ’s kingdom by enforcing the worship of God. Instead, they should aspire to clear the ground and make the road easy for pilgrims on their way. Their work is prerequisite and preparatory work. We shouldn’t ask governments to provide salvation. They can’t, and the vast majority of them will never want to anyway. Rather, we ask them, much more modestly and in ways that line up with their self-interest, to establish the necessary conditions for salvation. That way, the church can get on with its work of making disciples.

The good news is, Jesus will build his church. No, the worst governments cannot stop the Holy Spirit. Yes, God often moves underground, undisclosed to governments. But bad governments, from a human standpoint, really do make the church’s work difficult. Christians should work for good governments.

How?

(1) Pray. Paul urges us to pray for kings and all in high positions so that we may lead peaceful and quiet lives. “This is good” and “pleasing in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all people to be saved” (1 Tim. 2:3–4). We pray for our government so that the saints might live peaceful lives and people will be saved.

(2) Ask Scripture what God has authorized government to do. God authorizes the government to do some things (like prosecute murder) but not other things (like enforce conversions). So before you ask, “How should I vote?” or “What should I protest?” or “What should we lobby for?” first consider what God tells governments to do. That’s been the point of this entire chapter. No, Scripture doesn’t speak to the specifics of law. It speaks more like a constitution, establishing basic powers and lanes. I’ve argued in this chapter that God has given government a narrow, protectionist lane. You might disagree on how wide that lane is. Very well. Let’s have the conversation with charity and humility. Yet we have a clear criteria by which to discuss it: what does God authorize?

(3) Engage. For the sake of loving our neighbor and doing justice, we should not disengage from political cares. We should engage by employing whatever stewardship God has given us, whether we’re a voter or the cupholder to the king. We render to Caesar what is Caesar’s. In a democratic context we do this by voting, lobbying, lawyering, or running for office. Even in an empire, Paul, for the sake of the gospel, pulled the political levers he had. He invoked his citizenship and appealed to Caesar. Use such opportunities while you have them. Wherever we can build on common ground with non-Christians, we should.

(4) Acknowledge God in the public square. As a Christian, for instance, we should warn politicians who do injustice. Christians working in government, too, should be willing, when it serves good purposes, to point to God. “Now therefore, O kings, be wise; be warned, O rulers of the earth. Serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling” (Ps. 2:10–11). Does this mean a president can take the oath of office with his hand on the Bible? Should he invoke God in his speeches? Can a pastor open a school board meeting in prayer? Answers to questions like these will have to be judged on a case-by-case basis. As a general principle, I’m more comfortable with an officeholder speaking for him or herself rather than presuming to speak for the nation, as the words of constitution do. We don’t put God’s name into mortgages or business contracts, even though they govern the relationship. Still, I see no biblical reason for why a Christian office holder should not use his or her pulpit to call a people to repentance (see Jonah 3:6–9).

[1] Matthew T. Martens, Reforming Criminal Justice: A Christian Proposal (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2023), 325.

[2] See, e.g., Nicholas Wolterstorff, Justice: Rights and Wrongs (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), ch. 16.

[3] In other words, it’s easy to affirm, “The government should acknowledge God,” if the government consists of one person—the king. This is merely a moral claim about what the king should do. Yet when we make that same claim when talking about a form of government that involves a people, as with a democratic republic, things get complicated. If I’m a US senator representing my home state of Maryland, it’s true that I should acknowledge God and do so in my job. It’s also true that the other 99 senators and everyone who voted me in should acknowledge God. But if they don’t, would God have me draft official documents acknowledging him as if they spoke for the other 99 and all my voters, even though they disavowed Christianity? To use a real example, should the British government require a Hindu prime minister to take his oath of office by placing his hand on a Bible he disavows? Wouldn’t doing so turn his oath into a lie? My goal here is only to make the moral claim regarding individual officers of government: each one should acknowledge God. I’m not saying we should require others to say what they don’t believe.

[4] See “Feeding the Gods: Hundreds of Skulls Reveal Massive Scale of Human Sacrifice in Aztec Capital” (June 21, 2018), accessed December 3, 2022, https://www.science.org/content/article/feeding-gods-hundreds-skulls-reveal-massive-scale-human-sacrifice-aztec-capital.

[5] An “established” church is one that enjoys the patronage of the state. Its doctrine and practices receive the endorsement of the state. Its clergy and members receive certain advantages from the state, if in no other way than financially. And, any changes to the doctrine and practice of the religion require the consent of the state.

[6] “An indirect tax levied on goods and services, such as sales of land, houses, oil, and grass” (Colin G. Kruse, Paul’s Letter to the Romans Pillar New Testament Commentary, D. A. Carson, gen. ed. [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2012], 499). Kruse quotes from Thomas M. Coleman, “Binding Obligations in Romans 13:7: A Semantic Field and Social Context,” Tyndale Bulletin 48 (1997): 309–15.