A New Christian Authoritarianism?

You might have noticed American life feels increasingly politicized. Just think about the conversations you’ve had as a pastor in the last two years compared to the last twenty.

Or consider the broader landscape: debates over national anthems at football games, rainbow flags adorning businesses, neighborhood “co-exist” lawn signs, pronouns in email signatures, a broad array of speech codes, diversity training in corporate America and the military, protests against a fast-food establishment, debates about COVID masks and quarantines as well as divisions over whether medical authorities are trustworthy, and the list goes on and on, pushing into more and more areas of life. We live in the era of The Political.

The cultural moment is captured in William Butler Yeats’ 1938 poem “Politics,” which begins with the epigram, “The destiny of man presents its meaning in political terms.” Yeats looked leftward and saw communism, rightward and saw fascism. Both ideologies made totalitarian claims—political claims on the totality of people’s lives, from art to romance to religion. The middle ground in European politics was vanishing, squeezed out by this authoritarianism on the left and right.

A few years later, around 1945, C. S. Lewis remarked, “A sick society must think much about politics, as a sick man must think much about his digestion.”[1] By this measure, it would seem we are an increasingly sick society. Moral division abounds. People feel an impulse to fix things. They assume government needs to act. And everything gets politicized.

Christians today hardly live between monsters quite as ugly as Yeats’. No one is yet calling for concentration camps. Yet if a nation’s “politics” refers to that place it goes to resolve disputes, punish the bad, and reward the good by governmental power, the creeping kudzu of politicization reveals our deepening moral, ideological, and finally religious divisions as well as the conviction that those divisions are so deep that only governmental power will resolve them. Creeping politicization, in other words, implies a creeping authoritarianism.

THE NEW CHRISTIAN AUTHORITARIANS

In response to the secular authoritarianism of the left, a growing chorus of Christian voices on the right have adopted their own authoritarian approach to politics. Whether they go by the title of “general-equity theonomist,” “Christian nationalist” “magisterial Protestant,” “Roman Catholic integralist,” or, in legal circles, “common good constitutionalist,” their basic pitch is the same:

The middle ground of classical liberalism’s restrained approach to governmental power has proven inadequate for maintaining a moral, religious, and just society. The liberal DNA of the American Experiment, following secular Jeffersonian and Madisonian trajectories, has betrayed us. The Experiment has become the “high church form of secularism.”[2] And “liberalism has failed because it succeeded.”[3] The liberal Experiment has matured (or, better, devolved) into the LGBTQ+ and so-called woke identity politics of the progressive left, which threatens its own authoritarianism. Therefore, we’re left with no choice except to adopt one of two authoritarianisms: the secular left’s or the Christian’s. So pick your side. If you think you can defend some form of non-authoritarian middle, you’re a “regime theologian.” You’re handing the sword to the godless authoritarians.

It’s a compelling pitch, and maybe it’s correct, historically speaking. Hope for a non-authoritarian option may vanish. The American Experiment is an experiment. Its main goal—that a people of diverse religions, worldviews, cultures, and ethnicities may live together peaceably around the shared affirmations of freedom, rights, and equality—may prove unworkable. As such, the future may indeed look like one authoritarianism or another.

Why is this post-liberal movement rising up now? When people feel existentially threatened, they reach for a strong man. Think of President Trump. He’s a playground bully that embattled people hide behind. Likewise, many American Christians increasingly feel existentially threatened. We no longer live in a positive world or even neutral world, but “negative world,” where “being known as a Christian is a social negative.” Theonomy, Christian nationalism, and magisterial Protestantism offer a theological strongman.

Meanwhile, other Christians watching the rise of this movement are slack-jawed that anyone would think it’s possible to renew Christendom now. Realpolitik responds, “Are you kidding me? You think our country would ever go for this?”

Yet in a way that’s just the point. In the history of political philosophy, fresh rounds of theorizing occur when people feel oppressed and embattled, whether Jefferson writing a Declaration in response to British imposition or Marx writing in response to the inequalities of industrialization. Those in power who enjoy the ease of majority-status don’t typically feel the need to rethink theories of government.

AUTHORITARIAN = POST-LIBERAL

What do I mean by authoritarian? For starters, I’m using the term in a historically descriptive fashion merely to mean “not classical liberalism.” These writers, in varying degrees, are post-liberal, like the critical theorists of the left. They believe the government should possess authority over religion and establishments of religion in a manner that liberalism does not, or at least does not intend to. They are also as likely to critique the freedom of speech and the press as defend it. “Every society restricts some forms of speech” is what they say when the topic comes up.

Liberalism is a contested term, but to avoid the weeds for now and get our head around what liberalism is in short order, just think liberty. Liberalism foregrounds liberty, as with the shared Latin root (liber means free). A just government, says liberalism, protects liberty and our rights to it.

These more authoritarian writers don’t begin with liberty, but with Lordship. Liberty is not foregrounded, authority is. “If [Jesus] is Lord, we should do what He says,” says Doug Wilson. “If He is not, then we needn’t bother.” For that reason, Wilson wants a Christian “theocracy.”

Yet don’t be fooled, Wilson says. So do you. So does everyone: “all societies are theocratic, and the only thing which distinguishes them is which God they serve.”[4] In fact, says Wilson, Radical Muslims understand the implications of lordship better than many Christians do: “Radical Muslims . . . are the ones who at least understand the nature of the conflict. If Allah is God, then follow him. If he isn’t, then we shouldn’t.” And just as this is true for Radical Muslims, so it’s true for Christians: “And I would say the same thing about Jesus.”[5]

These writers, in short, want a stronger government with more authority that constrains or places impositions upon people’s worldview or religion. Or, at least, they want a government that admits that this is what all governments do.

Writing in the American Reformer, Timon Cline is explicit about the need for a stronger government. Cline refers to himself as a magisterial Protestant, which is a slightly different vein of post-liberalism than Wilson’s theonomic vein. The magisterial Protestants invoke the magisterial reformers like Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli, and they rely more on natural law arguments than the theonomists. Yet they arrive at a similar location—a more authoritarian government. Cline, a state deputy attorney general by day and an astonishingly well-read theology writer by night, wants to see a new conservative right shed the “tired and deleterious dogmas” of the past like “small government.” “Market fundamentalism and libertarian fictions can no longer inform policy,” he says. Rather, “we need a party of opposition . . . a party of the state and a party of nature.” By party of nature, Cline means one that appeals to natural law, an idea that has grown in Christian academic circles as quickly as the cause of a nature-denying transgenderism has grown on the political left. Yet notice the other two things he says we need: we need a party of opposition—meaning, it opposes the establishment. And a party of the state—not small government but big, one that’s willing to establish Christianity.

If “theonomists” like Wilson and “magisterial Protestants” like Cline represent two theological traditions or perspectives—ways of making the argument—the label “Christian nationalism” is more of a political program. It describes what its adherents want for a nation, and they’ll employ both theonomic or magisterial Protestant arguments to this end.

To be clear, people might use the phrase “Christian nationalism” in one of two ways. Some might be referring merely to Christian influence on a nation’s lawmaking. That’s not my concern here. Others want to identify the United States as Christian essentially at a constitutional level, similar to how modern-day Israel might refer to itself as “Jewish” or Iran as “Muslim.”

The latter usage is my interest. Christian nationalists in this latter sense will appeal to both theonomic and magisterial Protestant arguments, since all three groups want a religiously muscular government.

For instance, independent scholar Stephen Wolfe, in his book The Case for Christian Nationalism, acknowledges that his argument is “not ‘conservative,’” at least not as measured by the standards of the conservativism that stretched from post-WWII to the early 2000s (p. 434). Instead, Christians need to be revolutionaries who are willing to overthrow the present system, even violently (p. 326). Wolfe calls for a “theocratic Caesarism” (p. 279), ruled by a Christian prince “who brings a Christian people to self consciousness” (p. 279). To this end, church and state should work together: “The church’s duty is to teach true religion, and the civil government must ensure that truth is taught and that harmful false teaching is restrained” (pp. 35657). Governments should therefore “suppress blasphemy, heresy, and flagrant disregard for public worship among the baptized” (p. 262, also 182).

ENFORCING BOTH TABLES OF THE LAW

In fact, I, too, believe that a Christian’s politics begins with the phrase, “Jesus is Lord,” which by itself would be enough for many non-Christians to count me as authoritarian.

I also believe Doug Wilson is right—minus the word “only”—when he says that “all societies are theocratic, and the only thing which distinguishes them is which God they serve.” As I myself put it in a book once upon a time, “Governments serve gods. This is true of every government in every place ever since God gave governments to the world. The judge judging, the voter voting, the president presiding, all of them work for their gods. No citizen or officeholder is religiously indifferent or neutral.” And in another book: “Not only shouldn’t the public square be naked, it cannot be. It’s nothing more or less than a battleground of gods, each vying to push the levers of power in its favor. Which means, there are no secular states, at least in terms of what the basis is for a nation’s laws. There are only pluralistic states.”

In my mind, the fundamentally religious nature of all our politics is beyond dispute, whether your name is Franklin Graham or Nancy Pelosi, Antonin Scalia or Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Republican or Democrat Party. Name one political or policy position you hold that’s not backed up by a moral perspective that itself is not backed up by a theological perspective. I don’t think you can, including a law that says we should drive on one side of the road or the other.

Yet here’s where my path (and I assume most American Christians) diverges with the post-liberals. I would also endorse the U.S. Constitution’s injunction against Congress making a law “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Like most American Christians (I assume), I’d say these First Amendment words are at least wise, if not fundamentally biblical. These writers would count them at least as unbiblical, if not also unwise.

Differences exist between the post-liberals, which I’ll get to momentarily, yet the crucial piece that unites them is this: they believe that God intends for the governments of the nations to enforce not just the horizontally directed second table of the Ten Commandments (commandments 5 to 10), but also the vertically directed first table (commandments 1 to 4). This, more than anything, is why I count them as post-liberal and authoritarian. My friend and Davenant Institute president Brad Littlejohn jokingly referred to himself and everyone else in this group as First Tabularians. They would enforce the first table or tablet of the law.

Littlejohn, like Cline, places himself in the magisterial Protestant camp. In fact, Littlejohn provides the most compelling biblical argument for enforcing the first table of the law that I’ve encountered. It’s simple, elegant, and summarized in seven quick steps (his words, condensed by me for length, follow):

- It is the task of government to punish evil and praise/reward good (Rom. 13; 1 Pet. 2).

- All humans know what good and evil look like from the natural law, which is restated and clarified by the Ten Commandments.

- Putting these two propositions together, then, we can say that governments should enforce both the first (1–4) and second tables (5–10).

- Based on the Protestant two-kingdoms doctrine, the government has jurisdiction only over the external temporal sphere, not over matters of the heart. Government cannot make people Christians, but it can forbid non-Christians from working against true religion (Christianity), which is the foundation of society.

- However, just because government can punish something doesn’t mean it should. If trying to stop some false religion does more harm than good, the government should tolerate it.

- The law has a pedagogical function, teaching us what to regard as good. Even if a law cannot effectively restrain some evil, it may limit its spread by its moral authority.

- Governments can promote as well as restrain. This was the basis of the American religious settlement: very few religious practices were actively restrained, but public institutions affirmed and celebrated the good of the Christian religion.

Points 1 and 2 provide the biblical premises which most Christians will affirm. The real argument begins with point 3. Before you reject it, consider it slowly and carefully. He’s surely right that God commands governments to punish evil and reward good. Romans 13:4 says so. I’m not sure he’s right that the entire 10 Commandments republish the natural law that can be known by all people (e.g., can the Sabbath be intuitively known?), but I think we can all agree the first commandment belongs to the natural law. Romans 1:20–21 says it’s known by all people. Therefore, if Caesar should punish evil, and if disobeying the first commandment is an evil recognized by every human as hardwired by God into the conscience, then shouldn’t Caesar punish those who disobey the first commandment?

In case you’re panicked that Littlejohn wants to convert people by the power of the sword, forcing them to worship God, he doesn’t. On principled grounds, point 4 pulls the reins back on Charlemagne’s warhorse. Of course the sword cannot compel belief, point 4 says. None of these post-liberal writers believes the government can. On prudential grounds, furthermore, point 5 tightens the reins a little more: don’t prosecute the first four commandments if doing so will do more harm than good.

Points 6 and 7, however, loosen the reins again: even if you don’t criminalize false worship, the government can still teach and promote right worship.

LIKE PARENTAL AUTHORITY

A useful analogy for getting your head around the post-liberal and “first tabularian” proposal, which they commonly use, is the authority of a parent. Christian parents know that they cannot compel their children to trust in Christ. Still, they can use their authority to create a family environment that is conducive to belief, or that makes belief more rather than less likely. Up to a certain age, for instance, you as a Christian parent require your children, saved or not, to attend church; and you probably penalize them in some form or fashion if they take the Lord’s name in vain or blaspheme Christ.

By the same rationale—my post-liberal friends reason—Christians should aspire to establish civil structures and cultivate a civil culture that broadly affirm the truths of Christianity and that make belief more rather than less likely, as in a so-called Christian home. If you’re able to install a Christian prince or win a Christian majority in your legislature, you can then work to create a similar environment in a nation. So place Christ’s name or the Apostle’s Creed in the constitution. Maybe impose penalties for Sabbath-breaking among believers. Probably place tight restrictions on false religion (you wouldn’t let your ten-year-old attend a mosque, would you?). And so forth.

Some might even argue there’s a biblical basis for equating parental and state authority like this. Israel’s governance was patriarchal, meaning civil and familial authorities blurred together. At one point David calls King Saul “my father” (1 Sam. 24:11), and Isaiah anticipates a day when “kings shall be you foster fathers” and “queens your nursing mothers” (Isa. 49:23; cf. Num. 11:12). Older confessions like the Westminster Confession or the Cambridge Platform therefore refer to civil magistrates as “nursing fathers” and “nursing mothers.” Never mind for a moment that these particular promises from Isaiah are fulfilled in the church, not in today’s nation states (see 1 Thess. 2:7b).

INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

Like Littlejohn’s fourth premise above, Wolfe also relies on the same two-kingdom’s distinction between internal beliefs and external actions. He argues, “Civil authority has no concern with true or false belief in itself, for civil authority concerns itself directly only with outward good and evil.” Or again: “False belief itself must never be the basis of civil punishment. False religion externalized is the only principled object of punishment” (ital orig., 357; see also 300f).

So consider blasphemy. “The public authority is bound to repress blasphemy, false doctrine and heresy,” Martin Luther remarked in 1538, “and to inflict corporal punishment on those that support such things.” How could Luther or the Magisterial Reformers think that way, if salvation is by faith alone? The key is this internal vs. external distinction. A government should not criminalize believing wrong things about God; rather, it should criminalize wrong acting about God, particularly insofar as such actions threaten to undermine the civil order. This is how restrictions on blasphemy or mosque building—both actions—begin to make sense even after admitting the government cannot compel the heart.

Furthermore, as secular speech codes grow tighter and tighter, costing people their jobs and livelihoods, who wants to deny that secular progressivists have their own version of blasphemy which they’re trying to stamp out?

By this token, the post-liberal perspective requires us to rethink religious freedom. Littlejohn acknowledges, with a friendly wink, that “saying you’re against religious liberty is a bit like saying you’re against kittens.” For his part, he loves kittens. But “just because I am unabashedly pro-kitten, that does not mean I cannot support reasonable restrictions on kitten rights for the sake of the common good.” Therefore, he and others are willing to place various limits on religious liberty. And this comes in varying degrees, as I’ll explain in a moment. Littlejohn himself would not restrict the ability of other religions to gather in their own houses of worship. Others like Wolfe might.

That said, Wolfe reassures nervous readers that he would not sanction “any government-run inquisition whereby authorities force people to profess their beliefs and then punish them on account of their alleged falsities” (ibid, n.8).

Why his proposals would not include such government-run inquisitions is unclear. After all, a person’s answers in response to a government-run inquisition surely counts as “religion externalized.” It’s also unclear what would prevent the next generation of adherents to Wolfe’s principle from pursuing government-run inquisition, even if Wolfe himself wouldn’t.

DIFFERENCES

Plenty of differences exist between these various brands of post-liberalism, and just about any generalization one might offer about them as a singular group may well provoke an exasperated eye roll in one or another.

For instance, the theonomists divide into the older Reconstructionist and the newer general-equity branches. The former appeals a little more directly to the civil codes of the Mosaic Covenant, while the latter argues we need to adapt those codes for different times and places.

Theonomists disavow all talk of religious neutrality in the public square, as I mentioned in the quote from Wilson above. This is because theonomists, whether Reconstructionist or general equity, are generally strong presuppositionalists. The magisterial Protestants, on the other hand, tend to criticize presuppositionalism and appeal instead to a common grace and natural law framework. That showed up in Littlejohn’s argument above.

The general equity theonomists, for all their willingness to expand the reach of government into first-table matters, also display a libertarian-like distrust of big government. They want to talk about putting Jesus’s name into the U. S. Constitution, but they don’t want to hear talk about sanitation commissions and fair-housing authorities. You may have also caught news of their protests against COVID restrictions, regarding them as tyrannical incursions by the government. At least some magisterial Protestants, on the other hand, are more comfortable with “big government” in the more common contemporary use of that phrase.

Magisterial Protestants like Littlejohn, who is an Anglican, believe in an established church. A general-equity theonomist like Wilson would prefer to avoid one, at least for prudential reasons. Wilson observes that a “strong argument can be made that establishment (official recognition and tax support for the churches) is the spiritual kiss of death for those churches. As a general rule, we do not look for spiritual vibrancy among all the state’s kept clerics.”[6] Yet while he argues “against establishment,” he distinguishes this from and argues “in favor of our forms of government being explicitly Christian.” Here he believes the Bible is on his side:

The magistrate has a responsibility to recognize that Jesus rose from the dead and that He is seated at the right hand of God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth. This is a scriptural requirement because the Bible says that every tongue must confess this in his mind and heart and to consult with the Church when he has questions about what it all means. . . . He should propose an amendment to the Constitution that consists of the text of the Apostle’s Creed. He should not put any particular denomination on the dole. If we don’t like welfare queens, we should not want to encourage bishop queens (193).

Two more differences to highlight. Some members of the authoritarian crowd do more to affirm the basic values of liberalism like liberty and equality. Littlejohn, whose PhD advisor was the Anglican Oliver O’Donovan, would broadly affirm O’Donovan’s so-called “Christian liberalism,” which leaves room for an established church, but also affirms “freedom,” “merciful judgment,” “natural right,” and “openness to speech” as the gift of Christianity to the world. Wilson, too, remarks, “I want a theocratic society that maximizes human liberty, including liberty of conscience.”[7] Wolfe, meanwhile, devotes a chapter of his book to a revolution that would dramatically overthrow the present liberal order and install a Christian prince. His system is also open to dividing ethnic groups and encouraging repatriation based on political preferences and each group’s distinct vision of the common good.

Finally, and this distinction is more my impression than how they would describe themselves: some authors foreground the work of the state in ushering in a Christian nation, treating the church almost as an afterthought. Others foreground the church, saying we’ll never achieve a Christian nation apart from evangelism and revival. Or at least they say we should foreground the church. Wilson is better than Wolfe in this regard. Why the latter group doesn’t actually spend more of their time talking about evangelism instead of spending all their podcasts, tweets, and articles on contemporary politics and long-term political arrangements is unclear to me. Still, I appreciate the positive affirmation of the priority of the church and the ordinary means of grace.

LEVELS OF COERCION

One of the challenges of this conversation is the amount of ambiguity that remains concerning what people mean or don’t mean when talking about “enforcing” religion or a command like “you shall have no other gods before me.” Does that mean publicly recognizing Christian holidays like Christmas? Establishing a church? Criminalizing all false religion? The question of whether we enforce the first commandment sounds like a yes/no question, as if the answer came with an on/off switch. But really the answer comes with a dimmer switch of options.

I can envision at least 6 clicks on this dimmer switch for what “enforcing” religion can look like. Number 5 represents maximal enforcement, while 0 represents none. To be sure, each step contains a spectrum within itself, but here’s a start. Further, each of these steps could be adapted for any religion or worldview, as the examples will suggest, though I have Christianity principally in mind:

Active enforcement

5) Penalty (fine, imprisonment, or execution) for false religious belief—“We’ll hunt you down and demand answers because you’re not allowed to even think otherwise.” Examples: USSR, Nazi Germany, Taliban.

4) Penalty (fine, imprisonment, or execution) for false religious public profession or advocacy—“Believe what you want; just don’t act on it. Don’t teach it in your assemblies or to your children.” Examples: colonial Virginia, Communist China, Muslim Iran, anti-conversion laws in certain states in India. Increasingly soft versions include: freedom of false worship in the privacy of one’s home, as with Catholic recusants in post-Reformation England; the freedom to build a place for public worship but without the right to proselytize, as was afforded to Jews in medieval Europe or Christians in the United Arab Emirates today; or the freedom to build a place for public worship and to proselytize, but still be excluded from various institutions like universities or government.[8]

Passive enforcement

3) No active penalty for false religious belief/behavior, but a formal affirmation and subsidy given to true belief/behavior by (a) financing establishments of true belief/behavior and (b) creating two classes of citizenship—“Believe, profess, and teach what you want, but we’re going to establish true belief (a) by using your tax money to subsidize ministries, buildings, clergy, and schools of true belief/behavior and (b) by preventing you from holding political office.” Examples: a number of early U. S. states, even Massachusetts until 1834. A softer version with (a) but not (b): present day United Kingdom or Sweden; arguably the progressive woke and LGBT left.

No enforcement, but religious speech and action by government

2) No penalty for false and no substantial subsidy for true religious belief/behavior, but symbolic affirmations of true belief/behavior by the government as the government—“Believe and practice as you want, but we as a government and nation will declare true belief in our founding documents, money, recognition of certain holidays, and oaths of office and court.” Examples: various U.S. state constitutions over the last 200 years; “In God We Trust” on the dollar bill; the opening sentence of the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights.

No enforcement, but freedom of religious speech and action by individuals in government

1) No penalties, subsidies, or symbolic endorsements as the government, but freedom for individuals in government to publicly affirm and promote their beliefs in office—“Speaking for myself as one senator among 99 who may not share my convictions, and who are free to vote according to their religious convictions, I would urge this chamber to outlaw abortion. Every unborn child is created in God’s image, and both Scripture and our consciences bear witness to God’s final judgment for all who depart from his law. ‘Kiss the Son lest he be angry,’ the Psalmist tells us.” Or: “Speaking as your mayor, we will no longer open up our public libraries to drag queen story hour. This new injunction is not a prohibition against a drag queen’s ability to worship themselves, their gods, or goddesses as they see fit. It is, however, my attempt as your mayor to protect marriage and the family, which falls within the jurisdiction that God has assigned to governments. You may vote me out, but so long as I’m here I will strive to faithfully uphold what is right.”

No enforcement; no moral pressure

0) Forbidding of public declarations of religious belief/behavior in any form—“Say or believe whatever you want in private; just don’t talk about it in office or in public. And certainly don’t impose it.” Examples: advocates of the liberal tradition coming out of Jefferson or Madison tradition, particularly those who seek to limit government’s role to proceduralist claims (i.e. outcomes are “just” if the right procedures are in place).

Three further words of explanation about this table. For starters, I’ve included step 0 since I assume many Americans (Christian and not) profess it. Yet I believe the position is both incoherent and a ruse. Every government fears one God or another, as I said earlier. And every person entering the public square seeks to pull the levers of power on behalf of his or her god. In other words, I don’t believe the position 0 actually exists, even though people place themselves here.

Second, the difference between steps 2 and 1 amounts to the difference between speaking for others and speaking for oneself, respectively. For instance, the Canadian Charter’s reference to “the supremacy of God” and the dollar bill’s reference to trusting in God both presume to speak for the nation, even though many in the nation may not believe those words.[9] It imposes an affirmation of belief where none may exist. It offers a nominal affirmation of faith. On the other hand, a senator who says the unborn are made in God’s image speaks for himself. He may impose his or her decision, even a religiously motivated decision, but not the claim that people believe things they don’t. I don’t mean to evaluate this distinction here, only make note of the fact that it categorically exists.

Third, I trust that a committee of lawyers and historians could improve this table. I’m neither. Still, I hope that, if nothing else, it conveys the point that vague language about “imposing religion” or “enforcing the first commandment” can mean a number of things. Littlejohn sounds like a 3, Wolfe a 4, Wilson sometimes a hard 2 and sometimes a soft 4 (as when he justifies the Crusades). For the record, I place myself at step 1. I am not in favor of a “Christian nation,” but I am in favor of “God-fearing governors.”

THE OPPOSITE ERROR: APPLYING RELIGIOUS LIBERTY LOGIC TO THE SECOND TABLE

Before explaining why or moving to critique, it’s important to offer one last word of sympathy to the post-liberals. They are onto something, meaning, they see real problems in the present moment, and liberalism has something to do with it.

A moment ago we observed, liberalism says a just government is one that protects and maximizes liberty. That’s not exactly what the Bible says a just government is. The Bible says a just government is one that punishes the wrong and rewards the right, as Littlejohn observed (Rom 13:4; 1 Pet. 2:14). Those are two different frameworks for moral evaluation in the public square. Not only that, from time to time, American Christians will forget about the right/wrong biblical framework for public morality and default entirely to the free/unfree liberal framework.

What’s the problem with that? It leads Christians to morally abdicate from the public square. They become unwilling to make any moral impositions on non-believers whatsoever. It’s as if their brains become so trained in the moral logic of liberalism, they become unable to apply any other moral logic than “freedom first.”

Where the liberalism of a first generation restrains them from applying the power of government to the first table of the law, calling this the requirement of religious liberty, a second generation applies that same restraining, religious-liberty logic to the second table of the law. Call it downward creep—from commandments 1 to 4 downward to 5 to 10.

Here are two classic examples, one on abortion (relevant to the sixth commandment) and one on gay marriage (relevant to the seventh commandment). First, Governor Mario Cuomo, in his famous speech on abortion at Notre Dame University in 1984, begins by invoking the principles of religious liberty: “I protect my right to be a Catholic by preserving your right to believe as a Jew, a Protestant or non-believer, or as anything else you choose. We know that the price of seeking to force our beliefs on others is that they might someday force theirs on us.” So far, so good. Most American Christians would agree. Yet then Cuomo applies this same first-table-restraining logic to second-table matters, including abortion:

The Catholic who holds political office in a pluralistic democracy—who is elected to serve Jews and Muslims, atheists and Protestants, as well as Catholics—bears special responsibility. He or she undertakes to help create conditions under which all can live with a maximum of dignity and with a reasonable degree of freedom; where everyone who chooses may hold beliefs different from specifically Catholic ones—sometimes contradictory to them; where the laws protect people’s right . . . to choose abortion.

Notice that the guiding moral framework for governmental activity is what protects freedom, not what’s right or wrong. It was this speech that provided a basis for the whole “personally opposed, publicly pro-choice” stance on abortion. “I accept the Church’s teaching on abortion. Must I insist you do? By law?” Cuomo asks. He spends the rest of the speech explaining why the answer is no. In short, he applies the logic of religious liberty regarding the first table to a second-table matter. It’s the equivalent of me affirming religious liberty by saying, “I’m personally opposed to Islam, but publicly I won’t stop you,” which I do say.

Second, David French makes the same argument for supporting same-sex marriage. Notice how the first sentence here appeals to the logic of religious liberty, while the second applies this logic to a second-table matter:

The magic of the American republic is that it can create space for people who possess deeply different world views to live together, work together, and thrive together, even as they stay true to their different religious faiths and moral convictions. The Senate’s Respect for Marriage Act [which sanctions same-sex marriage] doesn’t solve every issue in America’s culture war . . . but it’s a bipartisan step in the right direction.

In other words, he may be personally opposed to same-sex marriage, but he’s publicly supportive. Essentially, he asks Christians to forsake the government’s biblically assigned duty of adjudicating between right and wrong in second-table matters.

Both Cuomo and French affirm the right of Christians to make Christian arguments in the public square, calling it a constitutional right. Yet both tend to discourage them, saying we should instead make arguments built on shared values. Cuomo again: Catholic arguments will “divide us so fundamentally that it threatens our ability to function as a pluralistic community.” In other words, we should stick to making liberal, freedom-first arguments. French’s entire career, he’ll tell you, has been spent making these kinds of arguments.

The result of this downward creep is several generations of Americans, Christian and non, who lack any moral language other than “my freedom, my rights, my choice.” There’s no answer to such assertions, because it’s the only ethical language we have left that’s counted as rational and compelling in the public square. Say the very words “good” and “evil” and people will discount you as religious and authoritarian. It’s as if liberalism has completely addled our brains and left us unable to think publicly in the language of “evil” and “good” whatsoever. That’s a problem for Christians who believe the Bible says that governments exist “to punish those who do evil and to praise those who do good” (1 Pet. 2:14). Furthermore, if freedom-first arguments apply to abortion and gay marriage, why not apply this logic to every moral principle? Moral insanity results. Pretty soon the U.S. Department of Justice is filing a complaint for a Tennessee law forbidding minors from receiving puberty blockers and transition surgeries.

Now, with all that in mind, consider again how simple and intuitive the post-liberal solution looks: acknowledge that theology and morality are necessarily connected and legislate both—first table and second.

If the government should pick up the sword for the sake of right and wrong, it makes immediate and intuitive sense for it to pick up the sword for the sake of God. Which is why nearly every culture does. The ancient Greeks did. The Romans did. The Aztecs did. The ancient Chinese did and the modern communist Chinese do. Both radical and moderate Muslims do. Hindus do. Atheists and secular progressivists do. Basically, it’s an utterly human thing to claim that we need to protect our god or God with the sword, like Peter picking up the sword in the Garden of Gethsemane. It’s universal. Almost.

THE KEY TO THIS ENTIRE CONVERSATION: JURISDICTION

I have used the term “authoritarian,” I said, as a matter of historical description. Yet clearly I am also using the term evaluatively. I believe my post-liberal friends in this movement give more authority to the state than the Bible does, or at least than biblical wisdom recommends. Hence, I intend the negative connotations that come with the word authoritarian. I’m not saying the Bible gives us classical liberalism. But the Bible’s view of government overlaps with liberalism at least at these two crucial points:

- both impose a narrower jurisdictional lane on the government than theonomy and magisterial Protestantism by establishing a domain of religious liberty, which roughly applies to the vertically-oriented first-table-of-the-law matters;

- and both charge the government with protecting the basic political equality of all citizens in a way that authoritarianism threatens, because authoritarianism invariably treats some groups of people as less corruptible than others, namely, those who share your theology.

That’s why, in a society characterized by adherence to Christian morality, liberalism and liberal institutions “work” for producing relatively moral outcomes. To some extent, liberal institutions function like a mirror. They reflect a society’s reigning worldviews back to itself, whether that’s Christianity in the early United States, Confucianism in post-World War II Japan, Hinduism in India, Roman Catholicism in central America, or progressive secularism in Western Europe or today’s United States.

Let’s go back to Doug Wilson’s statement that “all societies are theocratic, and the only thing which distinguishes them is which God they serve.” I agree, except for the word “only.” Governments do serve gods, I said earlier. Every government ever has. Yet this is not the only thing that distinguishes one government from another. Some view themselves as possessing a broad jurisdiction, like the parent of a three-year-old who has complete charge over every aspect of the child’s life. Some view their jurisdiction as comparatively narrow, like the babysitter who is charged with keeping the kids alive and fed but not much else. Some impose more of their religion, and some impose less.

Biblical Christianity, I’ll argue at greater length in a separate piece, makes a narrower imposition, as does liberalism. That means, even when liberalism and its attendant institutions turn to betray us by trying to impose pagan religion on our children, biblical Christianity still constrains us from outlawing false worship. Yes, we should fight politically against those impositions on our children. Ban the drag queen from the public library if you can get enough votes. Work for better curriculum in public schools. Or maybe make tax dollars available to religious charter schools. In other words, do what you can to keep the drag queen’s false religion from applying itself in the domain (roughly speaking) of the second table of the law, as when a transgender state representative moves to allow “sexual attachment to children” to be classified as a protected sexual orientation. But, no, don’t impose a constitution on that drag queen that says he’s Christian when he’s not. Don’t tear down his Artemis statues, wherever those might be (see Acts 19:21–41). Don’t categorically ban him from running for public office by virtue of his false pagan religion. Rather, share the gospel widely so that people stop buying his Artemis statues and he goes out of business.

The key to this entire conversation is jurisdiction. It would take a larger theology of the government’s authority to demonstrate the point (see here) but, in short, God calls the government to enact a protectionist form of justice that roughly covers horizontal, love-of-neighbor, second-table matters, not a perfectionist form of justice that covers vertical, love-of-God, first-table matters. That latter assignment he gave to Old Testament Israel, and then handed it off to Christ and the church when Israel proved unable.

Consider just one biblical text in order to see the government’s horizontal-not-vertical jurisdictional assignment: the Bible’s “Great Commission” text for a government’s use of coercive force—Genesis 9:6. Notice first that the assigned jurisdiction is human to human or horizontal: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed” Notice second that the theonomists are correct—that horizontal-jurisdiction possesses a theological or vertical foundation: “for God made man in his own image” (Gen. 9:6). The horizontal and vertical are inseparable in all Christian ethics, political and otherwise. Yet notice, third, that God simply does not authorize force for sins against him. The criteria for coercive force is blood, not blasphemy. After all, all the mechanisms for due process depend on something measurable, and sin is not measurable by human tools, at least not until concrete horizontal evidence shows up.

In other words, I don’t believe we’re authorized by God to bar the Christian Scientist’s “freedom of religion,” at least not until it causes him to deny necessary medical attention to his children—when his vertical commitments cause horizontal harm. That’s when the government is authorized to step in. Likewise, I don’t believe we’re authorized by God to bar the drag queen’s pagan worship, at least not until it, too, makes second-table impositions. At that point, the government possesses the obligation to reward good and punish evil.

In other words, the Bible leaves what might feel like a frustrating tension in place. On the first hand, it tells us to use the sword to protect humans because they’re made in God’s image. On the second hand, it doesn’t authorize us to use the sword to protect belief in God. On the first hand, it suggests that a society that denies God will veer toward injustice since he’s the foundation of all ethics, as is happening in our own society. On the second hand, it doesn’t then give us the sword to fix the God-problem. Instead, it tells us to preach the gospel.

When Christians begin to insist “There must be a political solution to a decline in religious belief and the growth of injustice,” they’ve begun to succumb to a theology of glory instead of a theology of the cross. They’ve begun to trade in a hope for the next world with a hope in this one, even if unintentionally.

No doubt, Jesus’s disciples were frustrated by this tension, too. They wanted to fight with swords. Yet Jesus remarked, “If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting, that I might not be delivered over to the Jews. But my kingdom is not from the world” (John 18:36). Jesus’s servants should fight to love their neighbors and seek justice by fulfilling their political duties in the protectionist, horizontal, second-table matters. Yet they should not fight to expand his kingdom, using the sword or any tool of the flesh to actively or passively enforce belief in first-table matters (“enforce” as indicated by steps 2 to 5 in the table above).

REWARD THE GOOD, PUNISH THE BAD

If God has indeed assigned government a horizontal, protectionist jurisdiction, how do we understand Paul and Peter’s claims that God tells the government to reward the good and punish the bad?

Does that mean all good and all bads? Presumably not. That would make the government God, with an absolutely exhaustive reach into hearts, minds, and souls. Presumably, therefore, God means a subset of goods and bads.

Littlejohn says the natural law comprises that subset. Yet why that assumption? What’s the basis for it? Scripture doesn’t say that’s the case. It’s a missing premise on his seven points above. Furthermore, doesn’t the natural law apply to the desires and worship of our hearts? Yet Littlejohn’s version of two-kingdoms doctrine rules out the government’s consideration of the heart and its desires. So that would mean the government should prosecute some of the natural law, but not all of it, which is another missing premise. Also, don’t governments always (rightly) require criminal intent before prosecuting a crime? Don’t they (rightly) distinguish between things like premeditated murder and manslaughter? So, apparently, it’s not only the outer man which counts.

Furthermore, did Israel apply a two-kingdoms paradigm to their prosecution of the Ten Commandments? It doesn’t feel like they did. Read Deuteronomy 13. So why has that changed under the new covenant, especially if the new covenant doesn’t apply to the nations and their governments, but to God’s people? Speaking of Old Testament Israel, why make the assumption that governments today should do what its kings did? Their work was fulfilled by Christ and its work overtaken by the church. In short, Littlejohn’s arguement skates over lots of crucial details and hides a host of assumptions.

Yet back to the question of what’s the subset of good and bad that God intends government to prosecute. The sentence “reward the good and punish the bad” means different things depending on who you’re talking to. You probably have one set of goods and bads in mind if you’re addressing a parent, another set if you’re addressing a babysitter, another a high school teacher, another a car dealer salesroom manager, another a policeman. What you mean depends on the jurisdiction of each. Again, jurisdiction is key.

We should only ask the sword to do what Jesus would tell the sword to do.

CHRIST’S LORDSHIP OVER EVERY SQUARE INCH

Post-liberals are right to assert Christ’s lordship over everything. Christ is Lord over every square inch.

Yet post-liberals are wrong to claim that assigning government a narrower jurisdiction is tantamount to public atheism. Christ is Lord over every square inch, but he does not ask us to exercise his authority over every square inch in the same way. Through parents one way, through governments another, through churches still another.

Placing a limitation on Caesar’s jurisdiction is not to adopt public atheism or religious neutrality. It’s just to say he’s limited in what he can do, like a parent limits a babysitter. Period.

Now, within his jurisdiction, Caesar must only do what God would have him do, defining right and wrong, just and unjust, as God would have him define it, just as a babysitter should only do what the parent requires. Caesar should “kiss the Son, lest he be angry,” Psalm 2 warns. As quoted above, Wilson is right to say, “The magistrate has a responsibility to recognize that Jesus rose from the dead and that He is seated at the right hand of God” and that “every tongue must confess this in his mind and heart and to consult with the Church when he has questions about what it all means.” In fact, let me clarify the point further: the magistrate should do this not only as an individual person, but in his or her capacity as an officer of the government. Insofar as every government officer departs from the law of God within the jurisdiction that God has assigned government, God will judge that officer. I don’t know how else to interpret Revelation 6:15–17. It says that kings and generals will prefer a mountain falling on them to facing Christ’s wrath. Every unjust judge and jury, senator and major, will face God’s judgment not for failing to maximize freedom, but for failing to reward the good and punish the bad as God intends—within their jurisdictional lane.

So “yes” to these first sentences from Wilson. It’s the next sentence that takes a sharp turn down a wrong street: the magistrate should therefore “propose an amendment to the Constitution that consists of the text of the Apostle’s Creed.” Hold on. That’s a change of subject. It’s true a U. S. senator should acknowledge and obey God and do so in his job. Yet it’s another thing entirely to make that U. S. senator, together with the other 99, the judge of sound doctrine for the sake of the nation. That job belongs to the key-wielding church. It’s also another thing to place convictions into the mouths of people who don’t believe them. I assume Wilson doesn’t ask his non-Christian bankers to place the Apostles Creed into his home mortgage papers. Yet why not? In part, perhaps, because doing so would falsify those papers the second the non-Christian lender signed them.

In short, a “moral ought” (a senator ought to submit to God) does not equal a “sword-wielding ought” (the senator ought to use the sword to require others to submit to God).

Wilson tries to distinguish a church establishment from a Christianized government. The trouble is, Christianizing the government requires that government to establish itself as part church—a key-wielding judge and declarer of right doctrine. Church establishment and a Christianized government aren’t as separable as that.

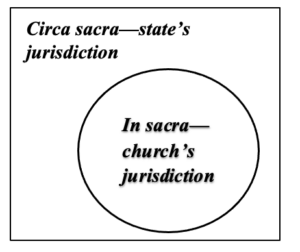

Elsewhere, Wilson says he maintains the distinction between circa sacra (around sacred things) and in sacra (in sacred things). The government, he argues, possesses jurisdiction only over the former. They can determine the fire-safety codes for your church building (circa sacra), but they cannot tell you what to teach in your church building. For my part, I’m pretty sure I agree with those jurisdictional assignments entirely.

The trouble is, Wilson then claims that both the original Westminster Confession as well as the 1789 American “downgrade” both maintain these same jurisdictional assignments, which is not quite right.[10] The original Westminster confession does indeed argue that the “civil magistrate may not assume to himself the administration of the Word and sacraments, or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven.” Yet in the very next sentence it contradicts itself by arguing the magistrate possesses the duty to ensure “that the truth of God be kept pure and entire, that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed, all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented and reformed, and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered, and observed” (original WCF 23.3).

These job assignments hardly keep the government on the circa sacra side of the line. Instead, they ask the government to tromp on into the in sacra domain, and in some ways do the work of the church. The American “downgrade,” on the other hand, fixes the internal contradiction. It argues it is the duty of governments “to protect the Church of our common Lord, without giving the preference to any denomination of Christians above the rest.” I don’t personally know a single Christian who would deny this job assignment—that governments should protect churches and their ability to do all that God calls them to do as churches. This is precisely what it means to give governments authority circa sacra.

EIGHT CRITIQUES

A full on critique of these authoritarian, post-liberal perspectives requires a fuller exposition of what the Bible positively says and doesn’t say about government. In other words, critique number one is “it’s not biblical,” which I’ve attempted here and here, as do other articles in this Journal (for starters, here, here, here, here. . .). Beyond this most fundamental critique worth multiple articles of its own, let me throw in eight additional critiques.

1. These post-liberal theories grant the church the wrong kind of authority, which works against the gospel and undermines the church’s gospel witness.

Making this point, I fear, will take a little bit of foundation-building on the topic of authority. So—deep breath—God has established two types of authority on earth. Both types of authority possess the authority to issue binding commands. One type may compel obedience externally with the threat of discipline (examples: state with the power of the sword; parents with the power of the rod; church with the power of the keys). The other type may not apply external pressure. It instead must seek to compel obedience by appealing to internal desire (examples: husbands by the power of love and empathy; elders by the example of a righteous life). I have labeled these two types the authority of command and authority of counsel elsewhere, and expand on it at length here.

The parent of a three-year-old can unilaterally enact consequences for disobedience. So can a policeman. So can a church over its members. A husband cannot, and an elder cannot (I say as a congregationalist). Rather, these latter two possess an authority of counsel.

An authority of counsel is a form of authority that strives to lead by appealing to internal desire—to hearts that, little by little, are learning to want to obey or follow. It’s a real authority because God commands the wife and church member to submit. Wives and members possess a real moral obligation that God will one day enforce. Yet the husband and elder, in the here and now, lack an enforcement mechanism. Instead, their form of authority forces them to love, to live with in an understanding way, to teach with great patience, to wait, to woo, and in all things strive toward provoking that internal desire (e.g., see 1 Tim. 1:5; Philem. 8, 9, 14).

Consider:[11] God gives husbands the opportunity to exercise this type of authority with the drawing power of a Song-of-Solomon-like love. This is his common-grace gift for all creation, and part of the underlying logic of the typological connection between husbands and wives and Christ and the church. God then gives elders the special-grace opportunity to exercise it with compelling lives of righteousness. Their righteousness should prove attractive to a born-again congregation, so that elders can say with Paul, “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1).

An authority of counsel doesn’t use force, but renounces force because doing requires it to rely on the beauty of whatever compels those new desires. It works best by pointing to that beauty. By inviting. By compelling with kindness. Then the hearts “under” it want to follow. It’s a form of authority suited to partnership, collegiality, and oneness.

All of this means that an authority of counsel is essentially evangelistic. You invite. You don’t force. Sometimes you correct, but mostly you compel with hope. You point to the law, but mostly you announce grace. You speak plainly, but you also speak kindly, because your goal is to win people over—wives toward unity, members toward righteousness, non-Christians to the gospel. You’re not to be a pushover, any more than Jesus was a pushover, nor to capitulate, any more than Jesus capitulated. Yet like Jesus calling his disciples from their fishing nets, so husbands and elders exercise authority by initiating and pointing in love toward the path forward. Wives and members, in turn, possess an obligation to obey, even as the non-Christian hearing the gospel does.

All that, then, is theological foundation for the following critique: theonomy, magisterial Protestantism, and Christian nationalism ask the church to face toward the world foregrounding the wrong kind of authority—an authority of command. They seek to compel the world with an external pressure or threat, which works against the evangelistic authority of the gospel.

In other words, the church should take an authoritative posture toward the world. It should say, “Jesus is your king. You should bow before him or judgment will come,” even as elders and husbands teach church members and wives of their obligations. Yet this authoritative posture amounts to an evangelistic authority of counsel. Even while individual members quietly work in politics as good citizens, the church collectively must renounce all external threat and pressure. Its authority is declarative, not coercive. Which means, it should instead seek to compel outsiders with the love and beauty of the gospel. After all, the church seeks a change of heart, so that people might join it based on new-creation, born-again, internal desires. Yet the more the church collectively dabbles in politics, the more it works against its ability to compel with beauty and love. It becomes like the husband who thinks he can demand love and affection, or the elder who thinks he can scare someone into righteousness.

Non-Christians resent churches for many reasons, many of which are not the church’s fault. Yet one cause of resentment which can be our fault occurs when the main foot we put forward into the world is the political foot. We do this, of course, when we love them less and our political safety more. Again, we play the part of the authoritarian husband or elder, who at best secures short-term results even while undermining long-term affection and love.

One lesson of the Old Testament is that the sword cannot produce true righteousness. External pressure, that is, doesn’t change the heart. Only the gospel, working through Word and Spirit, creates a new heart, and that heart, in its ideal form, wants to obey. An evangelistic authority of counsel, which is the church’s right posture toward the world, is suited to this ideal.

2. These post-liberal theories over-identify the state and the family and infantilize the citizens of a nation.

As we saw above, these post-liberal theories liken the state’s authority to a parent’s authority. It’s true we can draw analogies between one office and another, but we should be leery of mapping different offices on top of one another too precisely, even when both are an authority of command. Fathers who characterize themselves as kings of their own little castles and then treat their families as a king are storing up God’s judgment for themselves. Or, coming at it from the other side, I’ve not spoken with Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, but my guess is that he loves it when Chinese citizens refer to him as “Xi Dada.”[12] It seductively softens and personalizes this oppressive and tyrannical ruler, as with George Orwell’s infamous and totalitarian government which stylizes itself as “Big Brother.”

Paul describes a king as “an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer” (Rom. 13:4), while he instructs fathers “do not provoke your children” (Eph. 6:4). Governments punish. Parents discipline. That’s different. Or consider those Israelite parents who are instructed to teach their children God’s law in Deuteronomy 6—who does that work in the new covenant? Caesar? Or the church and Christian parents, the former equipping the latter? See Ephesians 6:1-3 for the answer.

I’d even say parents play an evangelistic and church-like role in a child’s life, nurturing and incubating the seed and earliest flowering of faith, until the child reaches an appropriate age for baptism and church membership. The parent does this, furthermore, not primarily with the threat of discipline, but with something more like the church’s own authority of counsel, exercised as instruction in love, especially as the child ages out of discipline.

Would anybody say the state can nurture and incubate faith in the same way two Christian parents can? Parent and government, clearly, are not the same office. The first possesses a very broad, almost totalitarian jurisdiction touching on the whole range of human existence: from teaching a child to speak, wipe himself, and memorize math facts to helping him love, think, argue, marry, and worship. It also covers the gamut from provision and protection to instruction and correction. A government’s jurisdiction is much narrower. Nothing in the Bible says Caesar possesses a discipling, training, nurturing job. He possesses a protective “keep everyone safe” job.

Yet parents also gradually surrender their authority of command over children. Little by little they stop disciplining, as a fully formed human emerges. John Locke puts it well:

Children, I confess, are not born in this state of equality, though they are born to it. Their parents have a sort of rule and jurisdiction over them when they come into the world, and for some time after; but it is but a temporary one. The bonds of this subjection are like the swaddling-clothes they are wrapt up in, and supported by, in the weakness of their infancy: age and reason, as they grow up, loosen them, till at length they drop quite off, and leave a man at his own free disposal.[13]

Theonomy and magisterial Protestantism, strangely, reverse course and put the swaddling-clothes back on the adult, infantilizing them, yet they ask the state to do it. It spanks the citizen, calling it a fine or tax, for using the Lord’s name in vain, thinking this will somehow induce or prepare that citizen toward belief.

Putting critiques 1 and 2 together, it’s worth remembering that flesh can only give birth to flesh, not the spirit (John 3:6). The sword cannot create spiritual life (2 Cor. 10:3-6). To acknowledge this fact is not to succumb to quietism. It’s to acknowledge that we are not the Holy Spirit and cannot coerce his hand.

This sense of our limitation should stand at the center of a Christian theory of political engagement. We cannot “expand” the kingdom through our political efforts. We can only protect or clear a path for it. The threat of God’s final judgment, shadowed dimly as the punishment of the state, presumably possesses some pre-evangelism power. Yet that power is limited indeed.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that Jesus and his apostles completely renounced making any kind of temporal threat for his kingdom-advancing purposes. Folks might respond, “Well, that was the condition of the Roman Empire.” Fine, but why did God choose that time to send his Son? Or, why didn’t the resurrected Christ, having made a payment for sins, then initiate a military putsch, or at least give his disciples a political strategy?

Christ could have, but relying on the sword to accomplish kingdom purposes undermines the credibility of the power of the gospel, and it dismisses the work of the Spirit.

3. These post-liberal theories give too little attention to the limits of government authority.

In their effort to expand the reach of the government into first-table matters, none of these writers, best I can tell, have spent much time meditating on the limiting principles of government. I’m never able to get answers to questions like, “So if ancient Israel doesn’t provide us with an actual political program, but at least a precedent for what’s hypothetically possible, why not a conquest-of-Canaan-like holy war? What principles do you offer to prevent such an enterprise besides prudential ones?” Their version of two-kingdom’s doctrine doesn’t do it. Consider Luther’s treatment of the peasants. Or Calvin and Michael Servetus. Or all the Reformation wars of religion.

Once you assign the government with actively or passively enforcing all Ten Commandments, it’s hard to find consistent principles of limitation.

On the other hand, running throughout Scripture is the demand that governments operate by the principles of accuracy, due process, impartiality, and proportionality.[14] These criteria are difficult if not impossible to apply to crimes exclusively against God. For that reason, God limits what we can prosecute, sanction, or subsidize to matters governing our relationships with other human beings.

By the same token. . .

4. They apply an inconsistent anthropology—people with beliefs different than my own are more corruptible than I am—and a rose-tinted view of authority.

Why assume that so-called Christian governments would prove more just, especially as one generation gives way to the next? Do people forget how the second generation of American colonialists abandoned the first generation’s Christianity? Or the terrible anti-semitism and racism which characterized the Magisterial Reformers in Europe as well as the more Christian governments of the United States?

In other words, Christian authoritarians quickly affirm that unbelievers in positions of power are corruptible and will use their authority unjustly. Yet they’re slower to acknowledge that they or their children will use authority in a corrupted fashion.

By the same token, Christian authoritarianism depends upon an idealized and rose-colored view of human authority, or at least its own authority. It’s as if Christians can remove themselves from the doctrine of the Fall and place ourselves inside of a realized redemption, at least in terms of how we will exercise authority in government. The doctrine of depravity applies more to the other guy than it does to me. No doubt, this point relates to the last one and the failure to reflect on the government’s limitations.

If only we only get our hands on the sword of state, we’ll surely do good. So will our children.

For my part, I believe we must simultaneously keep one eye on authority in creation and redemption (which does good) and one eye on authority in the Fall (which does bad). And that lesson applies to our own use of authority as Christians, too. This is why the Federalist Papers wisely worked to protect against abuses of authority. And I believe it’s also why the Bible doesn’t place the First Table into Caesar’s jurisdiction. There is something even worse than a corrupt government stealing and murdering, and that’s a corrupt government stealing and murdering in God’s name.

Keep in mind, also, that the strong man who is your friend in one moment will turn on you in the next.

5. They tend to work against basic political equality.

In the authoritarian framework, the concept of equality, politically-conceived, grows increasingly thin. “Equal rights” is not an historic Christian view,” says Wolfe. I’m not sure I agree, yet whether or not it is, should it be? Genesis 9:6 alone affirms the equal dignity of the all people; and the equal right to governmental protection; and the equal right to a government of due process; and, arguably, even an equal right to remain unhindered and protected in fulfilling the dominion mandate to “be fruitful and multiply,” which is the more basic command that 9:6 serves to facilitate (see verses 1 and 7).

In a conversation over coffee, a theonomist friend of mine asserted that it would be entirely fair to restrict the vote to land-owners or to men. His logic was, the Bible doesn’t require a democracy, but leaves room for a monarchy. Which means, no one is entitled to a vote. Which further means, we’re free to give it to some people rather than others, right? So why not give it to Christians, but not to non-Christians, or to members of your denomination, but not to others? There’s precedent for this type of thing in colonial America, after all.

God does indeed ordain certain unequal distributions of power, as between parent and child, husband and wife, elder and member, or governor and governed, as published in his Word. He establishes certain offices. Yet he also builds these offices on top of his own creation designs. The offices protect and clarify what’s endemic to that design; they have the potential—when handled rightly—to work for the good of every party. When, however, human beings began to establish permanent government structures or offices that arbitrarily discriminate between classes of people, giving a permanent authority to one class over another (landowner over non-landowner, rich over poor, man over woman, white over black, Christian over non-Christian, Muslim over non-Muslim) in places that the Bible does not reveal such structures or where such structures are not hardwired into creation design and natural law, those structures violate a basic creational equality. Moreover, history amply demonstrates that more injustices quickly follow.

6. Such “Christian” governments or nations misrepresent Jesus.

Though I’ve placed this sixth, one could argue that it’s the most important of all, which is why I’ve devoted another whole article to it here.

Christian authoritarianism broadly, whether of the theonomic or magisterial variety, presents political policies, programs, and structures as if they speak for Jesus and possess his endorsement. Laws and structures teach, as Littlejohn observes in point 6 above. Yes, they do. If we therefore “Christianize” the government, the lesson is: all its actions formally represent Jesus in the same way that a church formally represents Jesus as it binds and looses on earth what’s bound and loosed in heaven.

To be clear, this is why pastors and churches must be extraordinarily careful to tie their sermons and pronouncements to Scripture or what’s clear “by good and necessary consequence” in Scripture (Westminster Confession). A pastor with no Bible is a pastor with no authority. That’s why a pastor who tells you which home to buy, which girl to date, which march to attend, how much money to spend on a car, or which candidate you must positively vote for, is abusing his authority.

Yet now to the government’s work. Ninety-nine percent of its work is to make judgments in matters of prudence, not matters of biblical principle: what tax structure, what airline safety standards, what eighth grade math curriculum, what interest rate, what battlefield strategy, and so forth. Biblical principles may inform any given decision, but the vast majority of decisions can hardly be said to be “biblical” or “Christian” decisions. Yet once we slap the “Christian” label on a government, we’re at least subtly suggesting those prudence-based judgment calls come with a divine endorsement. Yet I’d no sooner want to identify our work of governance with Jesus as I would a particular approach to plumbing, engineering, or automaking.

Christians in the common grace sphere surely represent Jesus, whether a Christian mother, plumber, or mayor. How each conducts him or herself reflects on Christ. And some dynamics of mothering, plumbing, or mayoring might be distinctly Christian. Yet much of the work is common to humanity. The Christian mother, plumber, or mayor’s witness depends mostly on his or her display of Christian virtues (e.g. the fruit of the Spirit) amidst the work. This divide between our special grace and common grace work gets lost when we “Christianize” our vocations. That’s why Jesus never told us to baptize our jobs. He told us to baptize people.

Christian nationalism in particular baptizes a “nation” into Christ, even though Scripture affords not one instance of nations being baptized, only people “from” the nations (Rev. 5:9; 7:9). Other than the “holy nation” of the church, no nation will stand before God on Judgment Day. No nation is eternal. Yet declaring a “Christian” now effectively sacralizes that nation and gives it eternal standing. (See critique 6 of David Schrock’s article here.)

As these governing philosophies misrepresent Jesus, furthermore, they exacerbate the problem of Christian nominalism. It’s true, nominalism will show up any place the gospel is faithfully preached, as Jesus’s parable of the sower teaches. Not only that, moral, nominally Christian people might make for better neighbors in certain respects than immoral pagan ones. The question is, what’s the cart and what’s the horse? Christian nationalism treats nominal Christianity as a horse—something it purchases by “Christianizing the nation” in order to pull the nation toward better morality. To switch metaphors, it builds on nominalism, arguing that this is better than paganism. The trouble, of course, is that doing so grows nominalism, misrepresents Jesus along the way, and sends millions of people to hell assured of their salvation. It’s the seeker-sensitive church’s strategy. “Sure, we’ll hand out some false assurance cards, but people will get saved, too.” Better and more biblical, I’d say, to let faithful churches name who the Christians are, and then get to work trying to improve government.

7. These theories distract the church from its mission.

I discussed this at length in an editor’s note here.

To add one further note, these theories, together with the postmillennial eschatology often undergirding them, treat culture and the condition of society as “the report card of the church.» If the world is getting better, the church must be doing its job rightly. If the world is getting worse, the church must be failing to be faithful. Of course, that runs directly contrary to Scripture, where Jesus promises that we’ll have trouble in this world, and even more so, apparently, when we’re being faithful to him (John 16:33).

Consider for a moment, therefore, all the blogs and podcasts and tweets devoted to this topic. What do they urge you to do? And what do they urge you to expect? Do they challenge you to love Christ more, hate your sin more, share the gospel more, in spite of what persecutions come? Or do they call you a coward for not doing more to “own the libs”?

8. These theories have not overcome the temptation of the ideologue.

The possibility of picking up the sword for prosecuting the first table of the law feels like a strong solution to our present chaos and disorder. It will feel attractive to Christians under pressure. But I do think there is a genuine risk here of being seduced away from Christianity’s kingdom-built-on-sacrifice principles. Plus, some church members will be drawn by the appeal to strength, while others won’t, leading to division in churches.

To put this another way, this overall movement hasn’t solved the age-old problem of the ideologue or utopian. Ideologues give lip service to only advocating what’s realistic, but they love their theories a little too much. As such they fail to adequately account for the whole history of the oppression, abuse, and violence which has accompanied the ideologies and utopias that have preceded us.

In recent literature, the theonomists and Christian nationalists have bemoaned the secular and proceduralist versions of liberalism that have prevailed since the middle of the twentieth century. Yet they fail to take note of what spawned these historically recent versions. Mid-century theorists like Karl Popper, Isaiah Berlin, and John Rawls had become utterly exasperated with the historicist ideologies which produced the nationalist atrocities of World War One and the fascist and communist atrocities of World War Two and the U.S.S.R. (The Episcopalian Rawls lost his faith fighting in WWII.) Those ideologies, remember, emerged in the soil of Christendom, which, like postmillennialism, offered their own heretical versions of historical progress. Therefore, the post-war generation of scholars, surveying the devastations of German, Russian, Italian, and Spanish politics, decided, “Enough of your theories.” They redefined freedom negatively, removing all truth content from it; and they sought to establish the rules of liberalism in mid-air, unmoored by any comprehensive worldview. With that decision, they flushed Christianity, which offers its own version of positive liberty and a foundation for a better liberalism, down the drain with the rest of the dirty water.

So now a new generation of (mostly) young men, forgetful of history’s harder lessons, wants to theorize once more. They talk about theological retrieval, meaning, they open up old books of theology. Yet they would do well to open up old books of history, too. How did all that theorizing work out in the Reformation? Any comments on the wars of religion which decimated European populations for centuries? Anything to say about the ravages of anti-semitism? Or the burning of fellow Christians at the stake or drowning them in rivers? Or the rank hypocrisy of power-hungry princes and city magistrates and slave owners who were only too happy, day after day, to cloak their abuses and thievery in under the sacramental cloak of baptism? If we’re going to retrieve history, we should retrieve all of it, not just the clinically-sterilized formulas of old theology books or state constitutions.

The danger of theological retrieval, in other words, is that too often it’s ideologically driven. So it hunts through history selectively.

CONCLUSION

“If theonomy and Christian nationalism are wrong, what’s your alternative program?” A pastor friend sympathetic with theonomy asked me that question the other day.

It’s sort of like sitting next to a cancer patient in a hospital bed and having a fellow pastor who is sympathetic with the health-and-wealth gospel ask, what is your alternative program is to his name-it-claim-it prayers.