Is Christianity in Britain in Terminal Decline?

Is Christianity in Britain in terminal decline?[ii]

It is far too early to sign the church’s death warrant; news of its decline has been greatly exaggerated. Despite a perceived fall in traditional/established religion, the evangelical church in the UK is growing, with research showing that vibrant forms of Christian expression are on the up in diverse areas across the country.[iii]

INTRODUCTION: A NARRATIVE OF PRECIPITOUS DECLINE

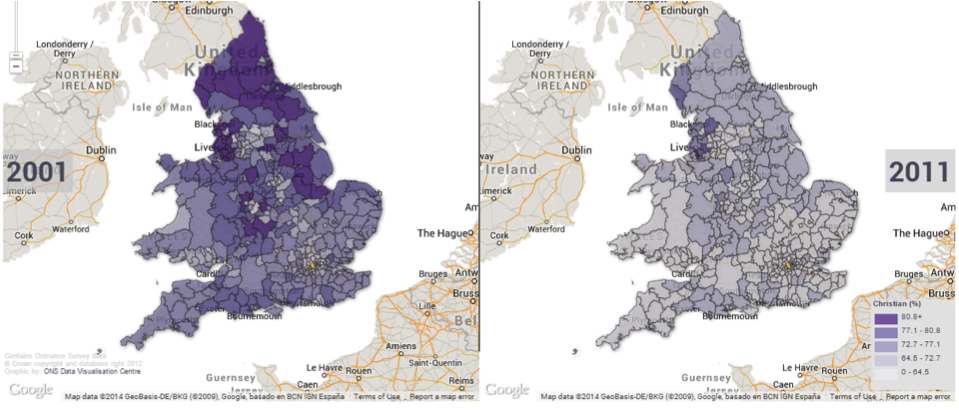

According to many of the widely published and accepted figures, both church attendance and professing Christianity in Britain are in rapid decline. The map above shows the generally accepted picture of Christianity literally fading away from the British population.

Though the statistics of decline are undeniable, in this article I shall argue that much (though not all) of the decline is a decline in nominalism; evangelicalism has been remarkably resilient. Within the evangelical camp I shall outline some areas for real encouragement, without minimising the real challenges for the church in a rapidly secularising mission field or ignoring some of the undesirable causes of numerical growth that encourage little, if any, growth in health.

As the census data for England and Wales itself states, “Between 2001 and 2011, there has been a decrease in people who identify as Christian (from 71.7% to 59.3%) and an increase in those reporting no religion (from 14.8% to 25.1%). There were increases in the other main religious group categories, with the number of Muslims increasing the most (from 3% to 4.8%).”[iv] North of the Scottish border there was a similar story, but with even fewer self-identifying as Christians: “In 2011 over half (54%) of the population of Scotland stated their religion as Christian—a decrease of 11 percentage points since 2001, whilst 37% of people stated that they had no religion—an increase of nine percentage points.”[v]

One could make all kinds of claims to explain away the reality of the drop.[vi] For example, the seriousness with which the nation took the question might be doubted. After all, following a successful internet campaign, over 370,000 self-identified as “Jedi.”[vii] But however one spins it, there is no denying that 12.4% fewer in the nation decided for whatever reason to self-identify as Christian.

Church attendance likewise has been in rapid decline. We have statistics that go back much further than those of the census, and they all paint a picture of a much more persistent decline: “In 1851 between 40% and 60% of the British population attended church, with the figure around 30% in 1900, falling to 12% in 1979, 10% a decade later, and a figure of 7.5% in 1999.”[viii]

It is easy to see why many believe the secularisation of Britain is almost complete, and that the church, as described by a former Archbishop of Canterbury, is “bleeding to death.”[ix]

There has been a great deal of analysis as to what has led to such a decline. In a world of exciting and cheap broadcast entertainment, people are frankly not so bored at home that they’d rather be bored at church. With the arrival of interactive and social media, people’s feelings of connectedness may have increased. The options of what else one might do on a Sunday morning mean that even those who occasionally attend church might be more inclined to go shopping, an option not available until the Sunday Trading Act of 1994.[x]

Social change has also led to the privatisation of religion. If the drop in those self-identifying as Christians in the 2011 Census may have been surprising, perhaps more surprising was that 72% of Brits self-identified as Christians in 2001 when only about one in ten of those professing Christians would be in church on any given Sunday.

In addition to this, the changing shape of religious education and worship in schools has led to growing ignorance of the gospel among the young. Whereas the law on the statute book still states that “In every school, there should be an act of collective worship in which each pupil can participate every day,”[xi] the reality is that there is now little gospel content in most schools. Religious education has shifted from primarily studying the Christian Scriptures to a comparative religion that will look at the festivals and ethics of various religions, but little of their core beliefs, and even less actual reading of the biblical texts.

POSSIBLE COUNTER NARRATIVES

There have been several recent attempts to suggest more positive narratives. Firstly, of course, theologically speaking, the true church only ever grows. Jesus keeps on keeping his promise, “For I have come down from heaven not to do my will but to do the will of him who sent me. And this is the will of him who sent me, that I shall lose none of all those he has given me, but raise them up at the last day.”[xii] But that is not to say that conversions will always outpace the rate at which the Lord calls his saints home.

Decline is declining

Some recent figures show that church decline is slowing: “While these increases are not sufficient to bring overall growth, these two key movements have, however, in effect, pushed the previous rate of decline back by about 5 years.”[xiii] Others suggest that church attendance is once again on the increase, at least in London: “Church attendances, in freefall for so long, have started to rise again, particularly in Britain’s capital city. Numbers on the electoral rolls are increasing by well over 2% every year, while some churches have seen truly dramatic rises in numbers.”[xiv]

Christianity has “gone dark”

Others see a residual Christianity that is much more privately held than publicly practised. Rather like Jack Bauer deep on a mission in 24, he might not have been in touch with CTU for a while, but everyone would be very foolish to think that he’s dead. The large-scale privatisation of religion should not be equated with its disappearance. Rather there is “a Christian memory which subsists in the general population, and is delegated to churchgoers and clerics for enactment until drawn upon ‘at crucial times in their individual or collected sense.’”[xv]

Decline has always been partial and local

Others point to areas of real growth amongst a sea of decline. “Some churches in some regions are declining, but . . . substantial and sustained church growth has also taken place across Britain over the last 30 years.”[xvi] Peter Brierley demonstrates that there are exactly the same number of denominations “with more than 10,000 members in 2008, which have decreased between 2008 and 2013 by, say, at least -15%” as those that have increased by at least +15%. This is not to deny that the declining denominations are generally both larger and older than the growing congregations.

But even here I’d be less optimistic about some of the areas of so-called growth. I cannot get particularly excited about much of the growth of black majority churches in London, where so many of them are entrenched in the prosperity gospel. So, Britain’s largest church,[xvii] the Kingsway International Christian Centre, has grown from 300 people attending in 1992 to 12,000. I fear that such growth is doing little good for the souls of people both inside that church who believe the lies and outside of it who have the name of Christ associated with it.[xviii]

Studies such as David Goodhew’s edited volume Church Growth in Britain[xix] that seem to look for growth wherever they find it as an encouraging sign of continuing life seem to forget that life comes through the Word (e.g. John 5:24, 6:63, 6:68). So, in the chapter on the rise of black churches, those that teach the prosperity gospel and those that teach a simple faith are compared only in terms of their ability to attract adherents, not at all in terms of their faithfulness to the gospel.[xx]

The decline of nominalism

It would be a vast over-simplification to say that nominal liberal Christianity is in decline but vibrant evangelical Christianity continues to grow, but it would certainly be the case that evangelical churches tend to decline less. The proportion of churchgoers who would call themselves evangelical has remained remarkably stable at around 2.5% of the population. In addition to this, of those denominations mentioned earlier that had seen 15% increase “apart from the Orthodox Churches and probably some of the Fresh Expressions churches, all are evangelical.”[xxi] The two largest denominations experiencing such growth, New Frontiers and the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches, are both explicitly Reformed in their theology. Those that had seen 15% decline were predominantly liberal or Catholic.

There are some things about the declining numbers of self-identifying Christians that I find encouraging. If over 72% of Brits understood themselves to be Christian, I fear for this country. I doubt that 72% of the population have ever even heard the Christian gospel, let alone entrusted their lives to Christ.

If people hear the gospel for the first time knowing that they are not Christians until they have repented and believed in Christ, I can only think that it is a good thing. I’d much rather see only those who trust Christ self-identifying as Christians, for nationalised false-assurance will be seen as far more perilous with the eyes of eternity than plummeting church membership.

A PERSONAL VIEW OF THE LAST 20 YEARS: WHY I’M CAUTIOUSLY ENCOURAGED

My own experience of church life in Britain spans the last four decades, only the last two of which have I paid much attention. My experience (other than school and college chapels) has largely been of Evangelicalism. I grew up attending an evangelical Anglican church that would have spanned both somewhat conservative and more charismatic forms of Evangelical Anglicanism, typified in turn by All Soul’s Langham Place, and Holy Trinity Brompton. I became convinced both of credo-baptism and Reformed theology as an undergraduate. Since graduating I’ve been a member of six churches in Britain: two Anglican, two FIEC (the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches), one Baptist Union, and one Grace Baptist. All have been within the conservative evangelical family, and so I shall focus on my view of conservative Evangelicalism with its encouragements and challenges.

I’m sure that similar stories could be shared from those in more charismatic circles such as the New Wine Network[xxii] or New Frontiers International[xxiii] or the rapidly growing networks of Black majority churches.[xxiv]

My experience typifies the non-denominationalism of British evangelicals. Other than some Anglicans who would not dream of leaving the established church, most evangelicals would look for a church that ‘felt’ like the churches they’d previously appreciated, rather than belonging to the same fellowship or denomination.

Such fluidity is both exciting for the potential of new church plants to draw people from many different denominational backgrounds, and explains their ability to grow (at least through transfer growth). However, this fluidity may also account for some of the decline in more established churches.

Far more important for the future of the church is not which areas of the church will get a “bigger share of the cake” of Christians who still attend church, but from which areas will the real growth come—growth in conversions, growth in disciples.

There are several areas that I find very encouraging for the state of the church in Britain due to my observations over the last 20 years.

Training

While attendance at evangelical theological colleges and seminaries has remained somewhat static over the last 20 years, there have been huge advances in the available routes into ministry.

For example, in 1991 the Proclamation Trust began the “Cornhill Training Scheme” for men and women who wanted to learn to teach the Bible better. A one-year course, usually studied over two years half time to give more opportunity for service in the local church, it “equips men and women for expository Bible ministry in the local church,”[xxv] whether in public preaching, teaching, women’s or children’s ministry.

About 50 men and women graduate from the course each year in London, and more recently Cornhill Scotland and Belfast have added to that number. The calibre of Bible-handling skills that the course gives people in just one year’s study is, in my opinion, quite extraordinary. Twenty-three years on, and there are several hundred workers across the nation and world who are better equipped to correctly handle the word of truth.

In addition to this course, other churches run their own training and associate programmes, similarly trying to equip trainees within the local church to handle God’s word well.[xxvi]

The Anglicans had been way ahead of Non-Conformists[xxvii] in resourcing and encouraging men into pastoral ministry. This was partly due to the financial resources available through the Church of England to send men to theological college, and partly due to a very subjective view of the internal call among many free churches. It has been very encouraging to see far more help and encouragement toward pastoral ministry within the free churches, from ministries that help people take the first steps of considering ministry as a possibility[xxviii] through formal training and more Assistant Pastorates.[xxix] The help that many are receiving is forming a virtuous circle: those who have received help tend to give it, and it is my impression that there are many more pastors than there were 20 years ago who see it as part of their role to raise up the next generation of pastors in a 2 Timothy 2:2-shaped ministry.

As an example of how independent churches are catching up with their Anglican brothers, when I went to Oak Hill College in 1999, I was one of three men training for pastoral ministry outside of the CofE. Now the College would take similar numbers of Anglicans and Independents, and provide equally suitable education for them both.[xxx]

Gospel Partnership

There have been several organisations that work across denominations for the health of the church nationwide. Let me highlight just three.

The Proclamation Trust.

The Proclamation Trust grew out of the ministry of Dick Lucas, the rector of St. Helens Bishopsgate for nearly 40 years. It “serves the local church by promoting the work of biblical expository preaching in the UK and further afield.”[xxxi] As such, it is like a “one mark of a healthy church”-promoting ministry. It would be hard to overestimate the impact that the Proc Trust has had. By teaching and equipping pastors to trust that the transformation of God’s people comes from the proclamation of God’s word, it unleashes the formal principle of the Reformation upon God’s churches. It works toward its end through publishing resources, holding conferences—most notably the annual Evangelical Ministry Assembly (EMA)—and running the Corhill Training Course mentioned above. Its impact continues to grow, exemplified from the move of the EMA from St. Helen’s to the Barbican in 2013 as it had turned people away through being fully booked for the previous two years. In the past 5 years 2,500 different people have attended, with about 250 first timers each year. That is a significant number for the UK church.

Gospel partnerships.

The gospel partnerships are a “network of Bible believing partnerships and churches throughout the UK seeking to reach the country with the life-changing news of Jesus. [They] exist to aid those churches and partnerships with resources on a wide range of topics.”[xxxii]

These networks have been useful to help local churches partner together in evangelism, from the nationwide “A Passion for Life”[xxxiii] missions in 2010 and 2014, to local partnership such as the lunchtime talks for workers in different areas of London.[xxxiv]

Church planting initiatives.

With many areas of the UK without Bible-believing churches with expository ministries, it is hugely encouraging to see several church planting initiatives across the country.

2020 Birmingham[xxxv] aims to “assist in the planting of 20 new congregations by the year 2020” within Britain’s second largest city. 20 schemes[xxxvi] has a similar goal in Scotland’s most impoverished neighbourhoods, as does the Antioch Plan[xxxvii] in London. Other nationwide church planting initiatives and movements include Acts 29 Europe and New Frontiers International.

Whether true Christianity is declining in Britain is still up for debate: biblical literacy is certainly in decline, and so church planting initiatives that reach those with no church background are enormously welcome.

AREA OF CONTINUING CONCERN

Within a rapidly changing mission field, the pressure for innovation is very strong. If we are to reach an adapting culture, we must adapt in our communication, particularly our ability to communicate the Bible to people who are utterly biblically illiterate, yet the majority of whom still self-identify as Christians. However, even among conservative evangelicals who love expository preaching, it would be seen as a truism that we can flex on everything except the gospel.

This has given rise to a desire to have new ways of doing church, whether “Fresh Expressions” or merely church plants. What often happens with both of these is younger people moving from established churches to new churches.

I fear that this is impoverishing both the new churches and the old. It is easy to see how the old churches are being impoverished. They have few young people and therefore possibly no future. Elderly saints struggle to care for one another, and may spend all the energy they have in keeping the church going, having little energy left for evangelism.

But the young church plants are also being impoverished, and not just by failing to make the most of the resources of church buildings. They are being impoverished in their discipleship by having few elderly people in their congregations to love, learn from, and be loved by. Discipleship is less intergenerational than it should be, and that is impoverishing everyone.

It’s not just in age that churches are becoming more monochrome. In a desire to reach the unchurched this year, I heard of one church entirely for skateboarders, and another right next to an area of urban deprivation that describes itself as being a church for “young professionals.”

However, there are a growing number of people interested in church revitalisation as well as planting churches for young people. All three of the church planting organisations I mentioned earlier want to be involved in both strategies.

CONCLUSION: THE CHURCH IN THE NEXT 20 YEARS

I am neither the prophet not the son of a prophet, so I hesitate to make detailed predictions about the future of the Lord’s church in Britain.

As nominalism continues to decline, those who don’t know Christ as Lord will have few reasons to claim his name. I fear that there will be fewer concessions made to an apparently shrinking minority of the population whose consciences are bound to Christ and his Word. It will be difficult. But we follow a crucified Messiah, and we should expect difficulty. “If the world hates you, keep in mind that it hated me first,” he said, hours before the world showed him the full extent of its hatred even as he was showing the full extent of his love.

I thank the Lord that at a time when persecution may well come, there has been a growing confidence that the Word of God equips the people of God to do the work of God. There is a small army of young ministers competent to handle that Word, and while that Word is being preached and lived, I trust the Lord will have many people in this land that he will bring to life by that Word. I’m looking forward to seeing what he will do, and I doubt very much that it would be the death of Christianity in Britain.

*****

[i] http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/interactive/census-map-2-1—religion/index.html Accessed October 2014 (As were all websites in this article)

[ii] By Britain, I here refer to the island of Great Britain comprised of England, Scotland and Wales, not the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland would require its own study and though there would be many similarities, it would not quite fit the mould of the rest of the UK.

[iii] Dr David Landram, quoted http://www.eauk.org/church/stories/death-of-the-uk-church-greatly-exaggerated.cfm

[iv] http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/key-statistics-for-local-authorities-in-england-and-wales/rpt-religion.html

[v] http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/People/Equality/Equalities/DataGrid/Religion/RelPopMig

[vi] For a survey of arguments not to take the data serious see Peter Brierley, “Nominal Christians” http://brierleyconsultancy.com/images/nominalism.pdf

[vii] http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/census-2001-summary-theme-figures-and-rankings/390-000-jedis-there-are/jedi.html

[viii] Garnett, Grimley, Harris, Whyte & Williams Ed, “Redefining Christian Britain: Post 1945 Perspectives” (London: SCM, 2007) 3

[ix] Ibid, 1

[x] http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1994/1841/made Accessed October 2014

[xi] https://www.churchofengland.org/media/1244326/qs%20and%20as%20re%20collective%20worship.pdf

[xii] John 6:38-39 (NIV)

[xiii] Peter Brierley, UK Christian Statistic 2: 2010-2020 http://brierleyconsultancy.com/images/intro.pdf p.2

[xiv] Peter Oborne, The Return to Religion http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/religion/8970031/The-return-to-religion.html

[xv] Ibid, 6, quoting Grace Davie, Europe, the exceptional Case: Parameters of faith in the modern world (London: D,L&T) 19

[xvi] David Goodhew Ed. Church Growth in Britain: 1980 to the present (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012) p3.

[xvii] http://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/feb/14/religion.architecture

[xviii] http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01b0n3z

[xix] David Goodhew Ed. Church Growth in Britain: 1980 to the present (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012)

[xx] Ibid, 109-113

[xxi] http://www.brierleyconsultancy.com/images/csintro.pdf 4

[xxii] http://www.new-wine.org/

[xxiii] http://www.newfrontiers.co.uk/

[xxiv] http://www.christiantoday.com/article/huge.growth.of.black.majority.churches.in.london/33012.htm

[xxv] http://www.proctrust.org.uk/cornhill/

[xxvi] Notably St Helen’s Bishopsgate and the Co-Mission network of Churches.

[xxvii] i.e. those not within the established church, the Church of England

[xxviii] E.g. the Hub Conference http://www.fiec.org.uk/what-we-do/article/the-hub and 9:38 http://www.ninethirtyeight.org/

[xxix] E.g. http://www.fiec.org.uk/what-we-do/article/partners-in-training

[xxx] This has been exemplified by the appointment of Graham Beynon as Director of Independent Ministry Traning http://www.oakhill.ac.uk/people/beynon_pickles.html

[xxxi] http://www.proctrust.org.uk/

[xxxii] http://thegospelpartnerships.org.uk/about-us/about-us

[xxxiii] http://apassionforlife.org.uk/en

[xxxiv] http://www.gospelatwork.org.uk/

[xxxv] http://www.2020birmingham.org/