Pastors on Social Media

On a recent Zoom call with half a dozen pastors, one raised the vexing topic of social media. Several of his members had urged him to speak up more in response to racial tragedies that had consumed the nation in previous weeks. “I’m not sure what to say or do,” he repined. His own thinking about the incident and its aftermath were still in process. Plus, did he have a responsibility to speak out on social media? Was he complicit in the injustice if he didn’t speak out? A lot of people had been pointing to quotes from Martin Luther King, Jr. and Elie Wiesel saying as much.

Another pastor immediately sympathized: “Some of my members want to hear more outrage from me. Others want to make sure I don’t sound like an echo of mainstream media.” He shrugged his shoulders, “I don’t think I satisfy either group.”

Knowing how to pastor in the age of social media can be bewildering. We feel its opportunities and its perils. We can encourage dozens or even hundreds of people with a tweet. But . . . we can also pick fights we don’t mean to pick. We can stir up foolish controversies. Apparently, we can even lose our church building by “favoriting” the wrong thing.

Yet the topic cannot be avoided. Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram are today’s watering holes, taverns, and town squares. As far back as 2013, 70 percent of Christian millennials read the Bible on their cell phone or the Internet, 56 percent would investigate a church’s website before attending, and 59 percent sought spiritual content online.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that 85 percent of churches use Facebook; 84 percent of pastors say it’s their church’s primary online communication tool; and 51 percent of churches say that at least one staff member regularly posts on social media.

Church consultants insist that your church must exploit social media because it helps people find you, builds community, displays your church’s vitality, meets people where they live, sells your ministry products, provides a venue for announcements, helps you educate and disciple, and so forth.

And it’s not just “low church” evangelicals who use social media. The Church of England asked members to post photos of Easter celebration with the hashtag #EasterJoy. Pope Francis invited his 18 million Twitter followers to join him on “a new journey, on Instagram, to walk . . . the path of mercy and the tenderness of God.”

So how should pastors think about their own use of social media?

THE UNIQUE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL MEDIA

To answer that, it’s worth thinking about the medium itself. You’ve heard the phrase “the medium is the message.” How does medium itself impact and shape what we say or do on social media? First, call to mind older mediums of communication, like the book, the newspaper, or television news. Now, in comparison to those, what’s unique about social media, and how does that impact the nature of communication? Here are five unique features worth noting.

1. It puts a printing press into everyone’s hands.

Social media places a Gutenberg Press in the palm of everyone’s hand—the smart phone. It democratizes the publishing industry. It levels the playing field. Your personal Facebook post appears right next to The New York Times’s, the disgruntled church member’s tweet right next to the president’s. By their appearance in the feed, no tweet or post possesses more intrinsic authority than another. All offer an equal claim to defining reality. A woman might spend years earning a Ph.D. in a field, but one clever word of snark from the man who has read one article on the topic divides the crowd and leaves her looking frivolous.

2. It promotes self-expression.

While newspapers have long made room for an opinion page and editorials, social media exists almost entirely for the purposes of self-expression. I post or tweet in order to tell you what I think, I feel, I believe. It provides a venue in which people share about themselves more broadly—from photos of family vacation to a list of schools one attended. Not only is a printing press in everyone’s hands, everyone gets to write their autobiography, only this autobiography is live, moment-to-moment, real-time.

No doubt, a person can do all these things—share their opinions and their family vacation photos—in righteousness.

Yet social media also plays to our conceit. It tempts us to think people want or even need to hear our opinions or see our photos. To the extent I neglect engaging with the world “out there” but remain fixed to my screen, I run the risk of defining reality by what’s on the screen. Without a doubt, social media is the perfect medium for a society that believes reality is socially constructed.

My posts and my interaction with the pages of others can become my reality: Here is the house décor I love, my top 5 romance movies, my favorite appetizers and desserts, my pet peeves, my reflections on social justice, my opinions on homosexuality and God, my views on the science of a global pandemic. Here is me. Here is the world I know and experience. If you disagree with one of my opinions, I will be tempted simultaneously to take your disagreement personally—to view it as a personal attack—as well as to view your disagreement as irrational because it defies my reality. And the irrational, of course, cannot be reasoned with. It’s dangerous. It needs to be castigated, insulted, shut down.

This is true whether I’m talking about the sublime or the ridiculous. In fact, the whole spectrum between these two begins to fuse together because they now belong to the same categories of my reality. I can talk about God or paint colors in the same way, with the same emotion, in this same venue.

3. It removes pre-publication accountability.

Like every other medium of communication and publishing, social media offers accountability. Say something stupid or wrong, and you will be hounded by the mob. You might even be “cancelled.” But what’s unique is that social media requires no accountability before the “Post” button is hit. There is no editorial oversight. Every man is his own editor and editorial board.

Not only that, the editorial oversight given to books, articles, and newspaper columns demands a time delay. A writer must wait for an editor to read, which means any flash of emotion or cockeyed certainties of 1 a.m. that compel you to write something will have had time to cool with the rising of a new sun. Yet social media allows me to instantaneously announce to the planet every flurry of rage, lust, and disgust. The medium affords no checks. They must come from the user.

4. It merges publishing with town-hall meetings, but with no accountability for the crowd.

Social media does not merely allow people to act the part of a publisher. It allows the crowd to act the part of a congregational church meeting or town hall meeting or even courthouse. When you speak, the crowd can speak back, offering their cheers or their sneers.

The trouble is, the crowd bears no accountability, and they remain relatively impersonal. In a church meeting or town hall meeting, when one person speaks, anyone responding will be held accountable for his or her response. Everyone’s names and faces are present. Plus, everyone will hear the back-and-forth of conversation—claim and counter claim—before decisions are made.

On social media, people read a post, offer a comment, and then move on. They engage in drive-by tweeting, or a drive-by trial. The whole court case—indictment, trial, and conviction—occurs in 280 characters. Case closed. A drive-byer’s name might appear above the tweet—“Joe Brown”—but that doesn’t mean much. Effectively, the tweet or comment comes without any personal context for “Joe”—no body language, no tone of voice, no history of conversations and personal interactions, just the lazy words “No. Just no” or “Do better.”

The anonymous or pseudonymous social media account is the source of even more trouble and rancor. At least “Joe Brown” will probably exercise some internal restraint because his name is present. But the pseudonymous individual—“Woke Bloke,” “Methodist Mom”—effectively walks into homes, throws a grenade, and then walks out, the whole time wearing a ski mask so that he or she lacks all accountability. Such users, I believe, are irresponsible, cowardly, and faithless, at least insofar as they style themselves as truth-tellers or prophets.

Too bad for the biblical prophets. They couldn’t keep those ski masks on! Jeremiah didn’t sit in his pit and John the Baptist didn’t lay his head onto the chopping block and whisper to themselves, “Wait, I could have used a pseudonym?” They faced jeers and flogging and imprisonment because they awaited a better city; this world was not worthy of them (Heb. 11:16, 36–38).

5. It cultivates comparisons, legalism, and tribalism.

Human beings have always been tempted to wear masks, put their best foot forward publicly, and encourage others to think better of us than we actually are. The structures of social media offer a handy vehicle for these base instincts. The teenager and her Instagram account, the young mom and her Pinterest board, the PhD candidate and his list of associations on Facebook, the ministry leader and his tweets offering solidarity—in all these places, one can be tempted to manufacture an outward image or to cultivate a pristine reputation that accords with the times.

Yet it creates a culture of comparison. Another teen sees that account, another mom those pictures, another would-be intellectual that list, another minister those affirmations—and they all compare themselves to one another. She wonders, “Is that the standard?” He asks, “Should I do the same?” We compare the carefully curated outside of other people’s lives with the messy inside realities of our own, as I heard a preacher once say.

These comparisons can then become vehicles for legalism—“maybe I need to do a better job creating more holiday traditions for my children like this mom does”—and that legalism gives way to tribalism, since our tribes typically root in our legalisms. My tribe, after all, consists of the people who keep the same rules I keep, value what I value, prove their virtue in the things I count as virtuous—my way of parenting, my politics and party, my lifestyle.

SUMMARIZING THESE DYNAMICS

All five of these dynamics, I’m arguing, are more or less endemic to the structures of social media. Social media platforms—the way they work—democratize publishing, promote self-expression, remove pre-publication accountability, provide the means of meeting-like feedback, and cultivate comparisons which (sometimes) yield a legalistic tribalism. To be sure, the technology is morally neutral. They can be used for the purposes of righteousness or wickedness, like any technology. A person can tweet or post on Facebook for the genuine good of others, exercising a proper restraint on themselves, accepting feedback humbly and graciously, and rejoicing in the victories and virtues of others. Yet every technology offers particular temptations and can encourage certain potentialities to moral, willful, fallen human beings.

What potentialities? In a nutshell, social media creates a space to speak up for the defenseless and a space for all the temptations of foolish and wicked speech because it removes the two things that every other society in the history of the world has used to shape and control public speech: access and authoritative structures. The tribal chief and his tribe, the Greek assembly and its votes, Horace Greeley and the laws of libel, have all had traditions and rules and guidelines for public speech. Yet by clearing so much of this away and granting everyone with Internet access a potentially global platform, it opens up public speech to the foolish and the wise both.

On the one hand, we can more easily heed King Lemuel’s instruction:

- Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy. (Prov. 31:8–9)

On the other hand, the foolish and the wicked are looking through open doors to a wide-open field.

- A fool takes no pleasure in understanding, but only in expressing his opinion (Prov. 18:2).

- Enemies disguise themselves with their lips, but in their hearts they harbor deceit. Though their speech is charming, do not believe them, for seven abominations fill their hearts. (Prov. 26:24–25)

Both kinds of speech have had free reign on this the landscape. And which kind of speech comes more easily in this world? (Admittedly, recent actions by Twitter or Facebook to patrol certain varieties of speech curtail some of this freedom.)

Yet the fact that every one of us now has the ability to comment publicly on our political leaders’ job performance, government policy, environmental science, the finer points of Trinitarian theology, the demands of pastoring, the complexities of race, the inequities of the marketplace, the innocence or guilt of the accused, and so much more doesn’t mean we have the wisdom and competence to do so. (Read Tim Challies’ recounting of the story of Apelles and the presumptuous shoemaker here.)

It’s strange to me, however, that so many presume otherwise. It’s as if getting a social media platform suddenly makes us all subject matter experts on everything.

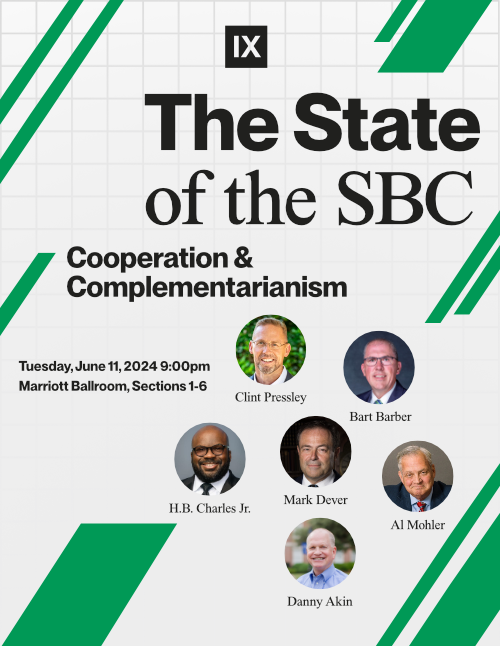

This reminds me of something I heard Mark Dever observe recently: our capacities have not increased one bit since the invention of the telegraph, the telephone, or the internet. And people’s desires for us to speak doesn’t increase our wisdom.

RECOGNIZE THAT SOCIAL MEDIA OFFERS A RIVAL COMMUNITY TO YOUR CHURCH

If that is the landscape, how should pastors think about speaking on it?

Add these five dynamics together and the big picture is this: social media offers a rival community to the local church. It’s not the only community or space that does so. Teams, friend groups, CrossFit gyms, and workplaces do the same. Yet social media is a particularly powerful rival because it’s self-selected and curated. It offers the voices of authority who tell us what we want to hear and the friends who like what we like. It caters to our natural predilections. It empowers us, giving us a platform for whatever we want. And because it shows up on our phone, it follows us to work, to the grocery store, and into bed.

Such challenges aren’t entirely new. Other celebrity voices have challenged the authority of the pastor. Radio and television have long tempted American Christians to heed the counsel of Robert Schuller and Jimmy Swaggert and James Dobson over their own pastors. That said, Schuller and Swaggert never “liked” your post through the television screen, and none of your favorite columnists at your favorite Christian magazine “followed” you. Social media platforms offer you this kind of reinforcement and favor. It also makes social connections and alliances between people that never would have been made otherwise.

Social media is particularly adept at offering a rival discipline (e.g., here)—one that’s far more severe and invasive than anything the ol’ local church can do. It shames, ostracizes, and vilifies. It costs people their jobs, friends, status, and more. People rightly fear being pulled into its vortex because the crowd lacks accountability, discernment, and love, and it offers no provisions for forgiveness. Political leaders, corporate heads, and ministry celebrities therefore do whatever they can to keep the swarm of digital locusts from descending on them. They’ll even bow when required.

The primary thing I’d encourage pastors to feel about social media, in other words, is caution. The crowd will exploit you for its purposes, to say nothing of crushing you. The crowd will also divide your church, whether that means provoking disgruntlement in just one family or stirring up political divides across the congregation. So be on guard, pastor. You’re stepping into a dusty Wild West town, and there is no sheriff and no law.

More dramatically, you are wrestling against principalities and powers, and those powers have keen eyes for your desire for a bigger audience and your church members’ affinity for other forms of social reinforcement. They want you to believe that other forms of wisdom are more reliable than God’s Word, other audiences more important than your humble congregation, other platforms more powerful for speaking, other kinds of impact you can make more lasting and significant. The second you begin to believe these things you have begun to compromise your calling as a pastor.

REMEMBER TO WHOM YOU ARE ACCOUNTABLE—GOD AND YOUR CHURCH

Most crucially, therefore, remember to whom you are accountable as a pastor: first God, second your church. You are not accountable to the world wide web. It did not make you a pastor. You will not give an account for it in the same way you will give an account for your congregation (Heb. 13:17).

Which means, first, that you don’t need to speak there. You need to speak with your church. And climbing onto one social media platform or another will raise expectations among members of your church that you should use that platform to address the issues of the day. If you don’t want those expectations, get off the platform.

If you do choose to step onto a platform, always keep these two audiences distinct in mind: your church and the rest of the internet. As a pastor, you’re called by God to speak to the first, not the second. That means you shouldn’t feel pressured into addressing everything and everyone on social media. You do have a responsibility as a Christian to speak up, particularly for those who cannot speak for themselves (again, see Prov. 31:8–9). But silence on social media doesn’t mean silence on an issue. The ordinary rules of wisdom, stewardship, calling, and moral proximity still apply. Your God-given job is to teach and equip and address any pertinent issues of the day in your church. You might feel called to speak more broadly. You are free to. But you don’t need to.

More importantly, the Bible does not require you to use this venue to speak. So brush off anyone who says you “must.” Encourage people to say “can” not “must.”

On the flip side, precisely because God is your primary audience, you need not be immobilized by fear of social media mobs. Speak what you believe God would have you speak, and let the hurricane winds of opposition blow. If you’re trusting and following God, those winds can cause your roots to grow ever deeper into the fear of God. In that sense, learning to speak on social media is a good opportunity for fear-of-God training.

LOWER YOUR EXPECTATIONS AND RECOGNIZE THE MEDIUM’S LIMITATIONS

The vast majority of pastors should probably lower their expectations of what they can accomplish on social media, recognizing the medium’s limitations. You’re not going to change the world on it. Lower your expectations about the arguments you can win, the persuading you can do, the doctrines you can teach, the justice you can accomplish. Meanwhile, remember that your biblically faithful week-in, week-out preaching can change the world for the members of your church.

Am I encouraging pastors to neglect potential stewardships God has given them? Shouldn’t we grab any platform God gives us? Certainly, pastors should be prepared to preach the Word “in season and out of season” (2 Tim. 4:2). Certainly, the apostle Paul set the example of preaching the gospel in all kinds of places, as should pastors (e.g. 2 Cor. 6:4–10).

Yet we should always fulfill our duties to speak with wisdom, which is why I spent as much time as I did reflecting on the medium of social media. It’s not apparent to me that we are persuading others as much as we think we are. The system just isn’t built for that. People change their opinions when they listen to voices they trust and when they feel affirmed as God-imagers, which books and articles implicitly offer readers merely by taking the time to lay out an argument. But this system simply offers quick bursts of “WHAT I THINK,” which doesn’t inculcate trust. Just the opposite: it’s rigged to create sparks and controversy. It doesn’t reward maturity and nuance so much as it rewards alarmism and hyperbole. A well-meaning Christian might step into this lawless gunslinger’s town, burdened by his conscience to speak what is true and just. Yet by opening his mouth he only manages to enflame the battles already underway and get his family and friends shot.

God may have given a few brothers and sisters effective social media ministries. Praise him. But that’s harder and rarer than it might look. Most of us would-be truth tellers should know that true words said at the wrong moment or in the wrong way can destroy more than they create (see Prov. 15:1; 25:15; Eph. 6:4; 1 Peter 3:7, 15).

A church, on the other hand, is wired by God to encourage relationships with real people. It’s meant to build trust and peace. This is why the Holy Spirit ordered the local church and its structures precisely as he did. He did not go to the trouble of revealing social media in his Word, but our churches. Which domain, therefore, do you think will prove more impactful over time?

I said a moment ago that social media offers a rival community to your church, and rival voices to your own as a pastor. Yet here’s a little hunch I have about Christians: the Holy Spirit wires born-again believers to want to trust their pastors more than other voices, at least when Christians and pastors are walking in the Spirit (see 1 Tim. 5:17). For instance, a ten-year-old boy is going to listen to his dad explain how to throw a baseball, if he’s a good and affectionate dad, sooner than he’s going to listen to his baseball coach. I think God designed it that way.

So it is, I think, with pastors and church members. Pastors are tasked with bringing the Word of God. That gives you, pastor, an advantage in the lives of your members over everyone else they’re listening to on Twitter or Facebook. Your voice carries a bit more juice. Yet—whoa!—what an extraordinary responsibility that places on you. You must only speak as a pastor where Scripture speaks. You must not abuse your authority by binding consciences beyond your realm of competence and authority. And you must never presume you’re capable of changing a heart by leaning on it just enough, as if you were the Spirit. All this will lead to a greater judgment (James 3:1).

WRITE YOUR OWN RULES AND KEEP THEM

What you must do—if I might put it like that—is to write your own rules of engagement for social media and keep them.

For myself, for instance, I work pretty hard to stay inside of certain boundaries whenever I post on Twitter. I’ve not actually written down my rules before, but they’ve been pretty clear in my mind. Here they are:

1. Stay within my areas of competence.

I feel competent to talk about ecclesiology, political theology and theory, pastoring, several ethical matters, and maybe a few other things. Notice, I didn’t say theology and politics. I was more specific. I have a Ph.D. in theology, but even here I’m careful. I didn’t feel prepared to wade into the 2017 debate on the Trinity. I read about politics plenty, but you won’t hear me addressing the debates on immigration or elections, at least substantively. I could. I have opinions, you know, both on the Trinity debate and the elections! And people might mistake my silence for indifference. But the world wide web is not my responsibility.

2. Avoid controversial topics.

That’s not to say I won’t address controversial topics in other forums. I’ve written articles on race, abortion, homosexuality, and complementarianism, for instance. And I’ve written books on politics. Yet the limitations of Twitter make this a dangerous location to have such conversations. You don’t have room to explain, qualify, establish a tone of voice, and so forth. The domain too often creates misunderstandings and unnecessary fights. See also point 4 here.

3. Avoid moment-by-moment commentary on news events.

The rationale of points 1 and 2 both apply here. I thank God for the journalists whose job it is to do this. That’s not my job. Summing up all three of these first rules, I’d say more Christians and pastors would do well to heed Paul’s words in 1 Thessalonians 4:11: “Mind your own affairs.”

4. Speak positively, not critically.

As in point 2, I’m willing to say critical things, but the 280 character-limit makes this difficult to do well. Tweets possess no context for the reader: no body language or tone of voice or room for qualifications, as I’ve been saying. Furthermore, the general culture of Twitter and civil discourse in America today, I believe, inclines people to read one’s tweets and comments in the worst possible light, especially when you say something critical. Bad-faith readings on social media abound, and the mob will quickly assume your motives are nefarious. If “love hopes all things,” there’s very little love here.

Therefore, I personally choose to avoid critical comments and snark in my Twitter presence. Critical Jonathan needs to go live someplace else. On the rare occasions I do say something critical, I bend over backwards to strike a courteous and affirming tone, even if snark is more fun and my heart wants to do otherwise. “Thanks so much, friend. Your comments really provoke me to think. May I push back on one thing, though?”

5. Speak to edify, not promote myself.

Before I tweet anything, I ask myself, will this edify someone, even a tiny bit? In other words, I use Twitter as an avenue for discipling other Christians. (Due to my job, I don’t assume many non-Christians follow me.) Now, I will promote books or other things I’ve written, and some heart work is involved here. If my gut tells me I’m promoting myself, I don’t. Otherwise, I’ll risk “sinning boldly,” as Luther said. Even when I share light-hearted comments on Twitter, as with a tweet in which I declared Coke Zero the greatest soft drink ever, my goal was to be friendly and warm up the space, if only by one-hundredth of a millimeter. Also, read “ 12 Questions to Ask Yourself Before Posting Something Online,” by Mark Dever.

6. Review resources before retweeting.

Before I commend someone else’s article or book, I read all of it. If I haven’t, I’ll say something to indicate I haven’t. “Looking forward to this book…” Or if I don’t agree with something, I try to find some way to indicate as much.

7. Always remember the members of my church might be watching.

I don’t believe a lot of my fellow members follow me on Twitter, but a few of them do. Therefore, I do my best to never say anything that will jeopardize my pastoral relationship with them.

8. Resist the temptation to tweet regularly, build a presence, and form a community.

If you want to build a brand or increase your followership, you need to establish a consistent “presence.” You do this by posting or tweeting several times every day and by replying in friendly fashion to comments. Offering play-by-play commentary on public events, whether playfully on something like the Super Bowl or seriously on traumatic national events, also helps to build a presence. You make yourself a regular voice for your followers. No, I’m not saying everyone who has a social media presence has done this merely to build their brand. People may have plenty of reasons. Yet that’s the only reason—for myself—why I could imagine trying to spend more time posting on Twitter. Plus, publishers and ministries and companies and schools all want you to do this, because it helps them.

And, honestly, it’s tempting. Maybe building a bigger platform would help 9Marks and give me the opportunity to push the ideas I care about. Yet a couple things have held me back. First, I don’t trust my heart. I’ll let God worry about the breadth of my ministry; I’ll focus on its depth. Second, I assume I would only be building a community of people who already agree with me. As I’ve implied throughout this essay, that’s what social media does best: clarify and concretize the disagreements that already exist. It doesn’t persuade. Any persuading that does occur happens either through bullying and fear, or through the unconscious enculturation we all experience in different environments. I’m not interested in either. Meanwhile, I’d rather spend my time building community and friendships elsewhere—home, church, neighborhood—because that’s where I will best grow and help others to grow, including across lines of difference.

Again, no judgment of those who do otherwise. I’ve been told again and again 9Marks needs a steadier social media presence, and that’s probably correct. Perhaps we’ll take steps in this direction. I don’t know. But for my personal handle, I’ve resisted social media’s unquenchable appetite for the steady and the regular. God doesn’t call me to build an audience on Twitter. He calls me to serve my family, my church, and my job.

I say all this about presence, pastors, because I assume the same is probably true of most of you. One friend of mine said, if you’re not on social media, you don’t exist. Okay. There’s some truth in that. But I don’t want to take that road. And I really hope most pastors around the world don’t either. Therefore, I tweet, quite simply, only when there’s something I want to say.

There are a few more rules I place on myself, but that gives you the idea. And no doubt these are all wisdom-based principles, not moral absolutes, that work for me. You might have different stewardships than me, but the main thing you should ask yourself is this: What specifically am I trying to accomplish in this space, given its risks, limitations, opportunities, and tax on other things I might do with my time?

If you want to build a bigger following quickly, ignore rules 1 to 4 and 8. Present yourself as the subject matter expert on everything, especially the controversial and immediately relevant stuff. You’ll attract followers. Plus, if you adopt a critical voice, you’ll quickly draw in the choir who is already singing your song. Yet to state the obvious: beware the possibility you might simply be hardening the different tribes against one another and not actually changing anyone’s mind.

THE GOOD AND THE BAD

Here are two things that I think are simultaneously true:

(i) social media has wonderfully helped bring more of the nation’s attention to the abuse of women, discrimination against minorities, and other injustices;

(ii) and the generally denunciatory and toxic nature of so much social media conversation has damaged the social fabric and unity of the United States and many of its churches, potentially sowing seeds for even more rancor and injustice in the future.

This is what happens when you remove all the boundaries and rules for access to public speech: you get the good and the bad.

My personal rules try to account for both, but, in all honesty, they are probably more calibrated to avoiding the bad. I believe I’m trying to exercise the wisdom of Proverbs and Paul, but presumably my personality and privileges also play a role. You might do a slightly different risk analysis.

One thing is certain, pastor: God is your first audience, your church is your second. Everything else on the internet is negotiable.