How DC Churches Responded When the Government Banned Public Gatherings During the Spanish Flu of 1918

For more resources related to COVID-19, visit our new site: COVID-19 & The Church.

* * * * *

As World War I was coming to a close, still another enemy was making its way toward the nation’s capitol: the Spanish Flu. Between October 1918 and February 1919, an estimated 50,000 cases were reported in the District of Columbia; 3,000 D.C. residents lost their lives.[1] At the peak of the pandemic, the DC government banned all public gatherings, including churches. How Christians responded provides some lessons and principles for responding to similar dilemmas in our own day.

THE RISING DEATH TOLL

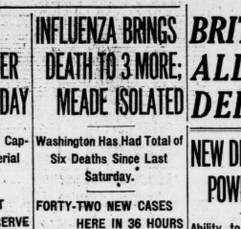

The first active cases in the District were reported in September 1918. Between September 21–26, six people succumbed to the flu. On September 26, Health Officer Dr. W. C. Fowler warned the public to be cautious about influenza but said he did not yet expect a full-on pandemic.[2] He was wrong. The next day saw three more deaths and 42 new cases.[3] From that point on, cases multiplied rapidly and deaths followed shortly thereafter.

When 162 new cases were reported on October 1, city officials took action. Public schools were ordered to close indefinitely and operating hours for stores were limited to 10 AM to 6 PM.[5] More closings followed in the next few days. On October 3, private schools and beaches were ordered to be closed. On October 4, the number of cases spiked; 618 new cases were reported. As a result, the city Health Officer Dr. Fowler called for additional bans on public gatherings, including church services, playgrounds, theaters, dance halls, and other places of amusement.

An article from “The Star” on Sept. 27

draws attention to the rising death toll[4]

On October 4, the headline of the DC-based The Evening Star read “Churches Closed While Influenza Threatens in D.C.” According to official documentation, the formal request used the following language:

Whereas the surgeon general of the United States public health service and the health officer of the District of Columbia have advised the Commissioners of the District of Columbia that indoor public assemblages constitute a public menace at this time; therefore, be it ordered by the Commissioners of the District of Columbia that the clergy be requested to omit all church services until further action by the Commissioners.[6]

THE RESPONSE OF PASTORS

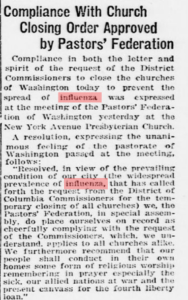

DC churches responded by calling an emergency meeting of the Protestant ministers on Saturday, October 5. There, they “voted unanimously to accede to the request of the District Commissioners that churches be closed in the city.”[7] As The Evening Star reported the next day that the “Pastors Federation of Washington” would comply with and support the safety measures called for by the city.[8] Gathering at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, the pastors released the following statement:

Resolved, in view of the prevailing condition of our city (the widespread prevalence of influenza, that has called forth the request from the District of Columbia Commissioners for the temporary closing of all churches) we, the Pastors’ Federation, in special assembly, do place ourselves on record as cheerfully complying with the request of the Commissioners, which, we understand applies to all churches alike. We furthermore recommend that our people shall conduct in their own homes some form of religious worship remembering in prayer especially the sick, our allied nations at war and the present canvass for the fourth liberty loan.[9]

A gathering of representatives from 131 African-American churches decided likewise to abandon services. Although responses to this order were mixed, churches demonstrated a unified response by complying with the directives of the DC government.

The Saturday, October 5 edition of The Evening Star listed all of the church services for the following day. Most headings simply stated: “no services.”[10] Some churches listed longer messages in their newspaper advertisements, explaining their choice to gather outdoors instead. One Presbyterian Church explained their cancellation of services in the following way:

Inasmuch as it has seemed wise to the Commissioners of the District, after careful consideration of the question, to prohibit the gathering of the people on Sunday in their accustomed places of worship, may I suggest that at the usual hour of morning service you gather in your homes and unite in common prayer to the God of Nations and of families, that He will guide us in all wisdom in this time of trial, that our physicians and public officers may be led in their performance of duty and be strengthened by divine help, that the people may be wise and courageous, each in his place. Let us never forget that “Help cometh from the lord which made heaven and earth.” Behold He that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep.[11]

OUTDOOR PUBLIC SERVICES

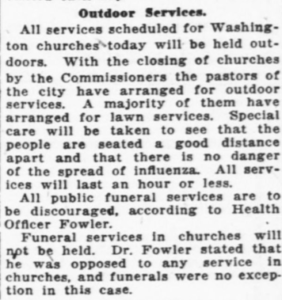

One way some churches managed to technically comply with DC regulations while continuing to meet was to obtain permits to gather outdoors. Examining the “Church Notices” section of newspapers at the time shows that many churches opted to gather outdoors on October 6—some in front of their buildings, others in public parks.[12]

The Washington Times | October 5, 1918[13]

The Washington Times reported the same on October 6: “With the closing of churches by the Commissioners the pastors of the city have arranged for outdoor services.”[14] Another paper reported the day before,

All churches will be closed tomorrow. Open air services will be substituted wherever possible. Numerous permits have been obtained to hold services in various Government parks in the city. These open air services will continue each Sunday until such, time as the District Commissioners decide the influenza epidemic is sufficiently abated to warrant resumption of meetings in church buildings.[15]

While churches were forbidden from gathering indoors, there was still the possibility of obtaining permits to gather outdoors.[16]

THE HEALTH DEPARTMENT’S RESPONSE

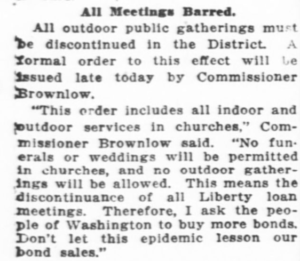

This move by churches to hold services outdoors was not well received by District Health Commissioner Brownlow, who on October 9 ordered the ban on public meetings to include outdoor church gatherings.[17] “This order includes all indoor and outdoor services in churches,” Commissioner Brownlow said. “No outdoor gatherings will be allowed.”[18]

OPPOSITION TO THE BAN ON CHURCH GATHERINGS

Churches responded by complying with this additional restriction on outdoor gatherings. Over the following weeks, the number of new cases and deaths from the virus kept increasing in D.C., reaching its peak on October 18 when 91 deaths were reported in a 24 hour period along with 934 new cases—including the DC Commissioner, Louis Brownlow. Then, slowly, the influenza began to decline. The number of deaths reported in a 24-hour period declined to 28 on October 28, and the number of new cases declined to 235.[19]

As these numbers began to decline, churches started to argue for a lifting of the ban. On October 25, an opinion piece on the Friday edition of The Star argued that churches should be transferred from the prohibited to the regulated class of gatherings, such as war workers in factories. The author listed two reasons:

(1) Because intelligent stringent regulation can prevent absolutely the crowding of the church edifices and can eliminate or reduce to a minimum the danger of germ distribution through such assemblages; and (2) Because the purposes of church assemblages are such as to entitle them to be the very last to be absolutely forbidden by the civil authorities.[20]

According to the author, church gatherings should only be prohibited when absolutely necessary because prohibiting church gatherings constitutes a threat to religious liberty:

Except in case of absolute, demonstrated unavoidable necessity public worship in the churches should not be prohibited by the civil authorities, because there is involved a certain infringement in spirit and effect of the free exercise of religious liberty. The authorities know that through national and civil loyalty their prohibitive order will be obeyed. [However] they should be reluctant to prevent men and women from doing that which their consciences and, in the belief of some of them, God’s command impel them to do.[21]

Additionally, the author argues that church gatherings actually have a positive effect of fighting the influenza:

In the influence of the churches upon the minds and souls of men, in quieting through strengthened faith in God the panic and fear in which epidemic thrives, the churches are potential anti-influenza workers, fit to co-operate helpfully with our doctors and our nurses, of whose fine record in these times that try men’s souls we are all justly proud.[22]

This author wasn’t the only one who opposed the ban on church gatherings. The very next day, October 26, another article reports that “strong pleas” were made to Health Officer Fowler and the Surgeon General by the Protestant Pastors Federation of Washington, DC. This group, which had exactly three weeks earlier voted to abide by the city’s restrictions on church gatherings, now sought unsuccessfully to obtain permission to gather for worship the following day. According to one newspaper, “The members of the delegation were told that until the health authorities feel fully assured that all danger of the spread of infection through large public gatherings has disappeared the ban would not be lifted.”[23] The Commissioners released a statement in response explaining that they did not “desire to interfere any longer than is made necessary by unusual conditions with the regular assemblage of the people in their churches.” However, they indicated no move to lift the general ban on all public gatherings, including churches, theaters, and moving picture houses until the influence of the influenza had abated.[24]

In a letter to the editor in that evening’s edition of The Evening Star, Rev. Randolph H. McKim, pastor of the Church of the Epiphany in Washington DC, protested the continued ban on church gatherings.[25] In the opinion piece, he argued in strong terms that “nothing has so contributed to that state of panic which has gripped this community as the fact that the normal religious life of our city has been disorganized.” He further protested that when the Federation of Pastors met with the City Commissioners to consider the matter, the Commissioners reasoned purely on “materialistic grounds.” No weight or consideration was given to the power of prayer or the comfort against anxiety that church gatherings would provide. In the authors’ words, “That prayer had any efficacy in the physical world was an idea that was given no hospitality” by the Commissioners.[26]

Letters and appeals from pastors to the Commissioners to lift the ban continued for several more days as deaths and new cases continued to decline. One Baptist minister, Pastor J. Milton Waldron, published an editorial on October 29, writing on behalf of “the eleven hundred members of Shiloh Baptist Church.” In the article, Pastor Waldron expresses his members’ concern that the city officials are carelessly “interfering with the freedom of religious worship.” In particular, his people feel that “the authorities are woefully lacking in reverence to God and wanting in a correct knowledge of the character and mission of the church when they place it in the same class with poolrooms, dance halls, moving picture places, and theaters.” As Waldron puts it, “The Christian church is not a luxury, but a necessity to the life and perpetuity of any nation.”[27]

THE BAN LIFTED

Then, finally, on October 29 the Commissioners released an order to lift the ban:

That the operation of the Commissioners’ order of October 4, 1918, requesting the clergy of Washington to omit all church services until further action by the Commissioners, be terminated on Thursday, October 31, 1918.

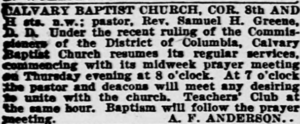

According to the DC health officer Dr. Fowler, conditions were such now that he felt assured by the fall in the death rate and the reduction in the number of new cases that “it was safe to open the churches this week [Thursday] and the opening of the theaters, schools, and other public gathering places Monday.”[28] A few churches placed advertisements in the Wednesday, October 30 edition of The Star announcing the resumption of services. For instance, Calvary Baptist Church announced that it would be resuming its mid-week prayer meeting on Thursday, October 31 as well as regular services on Sunday, November 3.[29]

On that first Sunday, the Reverend J. Francis Grimke preached a powerful sermon that was later published and distributed, “Some Reflections: Growing Out of the Recent Epidemic of Influenza that Afflicted Our City.”[30] In the sermon, Grimke acknowledges that there was “considerable grumbling” on the part of some regarding the closing of churches. However, he offered a defense of the ban on gatherings:

The fact that the churches were places of religious gathering, and the others not, would not affect in the least the health question involved. If avoiding crowds lessens the danger of being infected, it was wise to take the precaution and not needlessly run in danger, and expect God to protect us.[31]

In conclusion, the influenza of 1918 provides an example of how churches in Washington DC responded to a public health crisis and government orders to close churches. During one of the worst epidemics to ever hit our country, churches respected the directives of the government for a limited time out of neighborly love and in order to protect public health. Even when churches began to disagree with the Commissioners’ perspective, they continued to abide by their orders. This demonstrates a place for freedom of speech and advocacy while respecting and submitting to governing authorities.

[1] https://www.washingtonian.com/2018/10/31/the-forgotten-epidemic-a-century-ago-dc-lost-nearly-3000-residents-to-influenza/

[2] https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-washingtondc.html#

[3] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 27 Sept. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-09-27/ed-1/seq-1/

[4] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 27 Sept. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-09-27/ed-1/seq-1/

[5] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 02 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-02/ed-1/seq-1/>

[6] “The Evening Star,” October 4, 1918, p. 1. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-04/ed-1/seq-1/ Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[7]The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-2/. Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[8] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 06 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-06/ed-1/seq-7/

[9]Ibid.

[10] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-10/. March 10, 2020.

[11] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-10/. March 10, 2020.

[12]The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-2/. Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[13]The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-2/. Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[14] “The Washington Times,” October 06, 1918, NATIONAL EDITION, Page 19. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-06/ed-1/seq-19/. Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[15] The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 05 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-05/ed-1/seq-2/. Accessed on March 10, 2020.

[16] “The Washington Times,” October 06, 1918, NATIONAL EDITION, Page 19. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1918-10-06/ed-1/seq-19/

[17] The Washington Times, October 9, 1918, p. 3.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 28 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-28/ed-1/seq-2/

[20] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 25 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-25/ed-1/seq-6/. P. 6.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 25 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-25/ed-1/seq-6/. P. 6.

[23] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 26 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-26/ed-1/seq-1/

[24] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 26 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-26/ed-1/seq-1/

[25] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, October 26, 1918,

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-26/ed-1/seq-7/ p. 7.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 29 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-29/ed-1/seq-24/

[28]Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 29 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-29/ed-1/seq-1/

[29] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 30 Oct. 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1918-10-30/ed-1/seq-3/

[30]Grimké, F. J. (Francis James)., Butcher, C. Simpson. (1918). Some reflections, growing out of the recent epidemic of influenza that afflicted our city: a discourse delivered in the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, Washington, D.C., Sunday, November 3, 1918. [Washington, D.C.?]: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=emu.010002585873&view=1up&seq=3

[31]Ibid. 6.