12 Principles on How to Disagree with Other Christians

The consciences of Christians are remarkably similar, since we all have the same Word and the same Spirit. But on the edges of conscience, God has always allowed Christians a surprising degree of latitude in personal scruples. Paul didn’t command the stricter Christians of Romans 14 to get with the program and start eating meat as Jesus allowed. Nor did he command the meat-eaters to end their carnivorous ways on the outside chance they might upset the vegetarians. He expected them to get along until Jesus returned. (We use weak and strong in reference to the faith or the confidence of one’s conscience to engage in a particular activity [cf Rom. 14:22], not in reference to the strength or the weakness of one’s saving faith.)

But human nature being what it is, the stricter group was always tempted to judge those they saw as too free (“And they call themselves Christians!”), while the free group tended to look down on those with unnecessary restrictions (“those poor legalists!”). Fortunately, Paul condemned both attitudes.

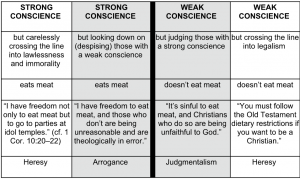

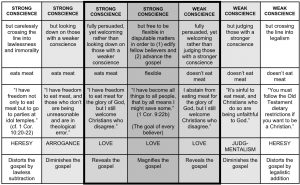

But disunity isn’t the only danger. Arrogance and overconfidence among the strong made them ripe for a kind of sin-all-you-want heresy called antinomianism. Meanwhile, the judgmentalism of the stricter believers tended to push them into the legalistic heresy of the Judaizers.

None of these four attitudes on conscience disagreements pleased God; in fact, two of them were outright heretical:

Satan had his axe poised to take advantage of this natural split. What would be Paul’s glue to go into that gap and hold these churches together in the midst of conscience disputes? It would be the glue of Christian love as articulated in Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 8–10. The chart below inserts Paul’s threefold solution of love into the growing split that threatened the early churches. Take time to look carefully at Paul’s solution of love that leads to unity:

The three center columns are derived mainly from Paul’s brilliant, Spirit-inspired analysis of conscience disagreements in Romans 14 and 15. In these two chapters, Paul offers 12 principles to ensure the strict consciences of the weak would be respected, while still allowing for the legitimate freedoms of the strong.

Here they are.

1. Welcome those who disagree with you (Rom. 14:1–2).

“As for the one who is weak in faith, welcome him, but not to quarrel over opinions [NIV: “without quarreling over disputable matters”]. One person believes he may eat anything, while the weak person eats only vegetables.”

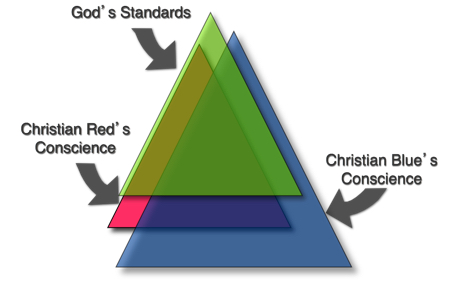

By now you’ve probably already put yourself into a “strong conscience” or “weak conscience” box. But the fact is, in most issues, you’re probably both weak and strong at the same time in comparison to others. There are almost always people to your left and right on any given disputable matter. This means that, depending on the situation, God will call you to obey Paul’s exhortations both to the weak and to the strong.

2. Those who have freedom of conscience must not look down on those who don’t (Rom. 14:3–4).

“Let not the one who eats despise [NIV: “treat with contempt”] the one who abstains, and let not the one who abstains pass judgment on [i.e., be judgmental toward] the one who eats, for God has welcomed him. Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another? It is before his own master that he stands or falls. And he will be upheld, for the Lord is able to make him stand.”

Isn’t this always the temptation of the strong, to look down on and despise the strict “legalists”? Paul condemns this attitude of superiority.

3. Those whose conscience restricts them must not be judgmental toward those who have freedom (Rom. 14:3–4).

And isn’t this always the temptation of those with a weaker conscience on a particular issue, to pass judgment on those “antinomians”?

Why are these attitudes so wrong? Paul gives two reasons:

1. “God has welcomed him” (14:3c). Are you holier than God?

2. “Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another?” (14:4a). You are not the master of other believers.

We’re not saying these third-level issues are unimportant. It’s okay to talk about them, and even preach about them. It’s okay to tweet and blog about them. But with at least two conditions: Have the right spirit, and have the right proportion.

4. Each believer must be fully convinced of their position in their own conscience (Rom. 14:5).

“One person esteems one day as better than another, while another esteems all days alike. Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind.”

The first great principle of conscience is that God is the only Lord of conscience. This point, however, brings us the second most important principle of conscience: obey it! God didn’t give you a conscience so that you would disobey it.

This doesn’t mean your conscience is always right. It’s wise to calibrate your conscience to better fit God’s will, which is why we have a whole chapter on conscience calibration in our book. But it does mean that you can’t keep sinning against your conscience and be a healthy Christian. You must be fully convinced of your present position on food or drink or special days—or whatever the issue—and then live consistently by that decision until God leads you by his Word and Spirit to adjust your conscience.

No two believers have exactly the same conscience. That’s why we need Romans 14! But the truth that needs to burn into all of our hearts is that no Christian has a conscience that matches God’s standards completely. No one.

5. Assume that others are partaking or refraining for the glory of God (Rom. 14:6–9).

“The one who observes the day, observes it in honor of the Lord. The one who eats, eats in honor of the Lord, since he gives thanks to God, while the one who abstains, abstains in honor of the Lord and gives thanks to God. For none of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself.”

Notice how generous Paul is to both sides. He assumes that both sides are exercising their freedoms or restrictions for the glory of God. Wouldn’t it be amazing to be in a church where everyone gave each other the benefit of the doubt on these differences, instead of putting the worst possible spin on everything?

6. Do not judge each other in these matters because we will all someday stand before the judgment seat of God (Rom. 14:10–12).

“Why do you pass judgment on your brother? Or you, why do you despise your brother? For we will all stand before the judgment seat of God; for it is written, ‘As I live, says the Lord, every knee shall bow to me, and every tongue shall confess to God.’ So then each of us will give an account of himself to God.”

If we thought more about our own situation before the judgment throne of God, we would be less likely to pass judgment on fellow Christians.

7. Your freedom to eat meat is correct, but don’t let your freedom destroy the faith of a weak brother or sister (Rom. 14:13–15).

“Therefore let us not pass judgment on one another any longer, but rather decide never to put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of a brother. I know and am persuaded in the Lord Jesus that nothing is unclean in itself, but it is unclean for anyone who thinks it unclean. For if your brother is grieved by what you eat, you are no longer walking in love. By what you eat, do not destroy the one for whom Christ died.”

Free and strict Christians in a church both have responsibilities toward each other. But the second half of Romans 14 places the bulk of responsibility on Christians with a strong conscience. One obvious reason is that they claim to be strong, so God calls on them to “bear with the weaknesses of the weak” (Rom. 15:1). Not only that, of the two groups, only the strong have a choice in third-level matters like meat, holy days, wine, etc. They can either partake or abstain, whereas the conscience of the strict allows them only one choice. It is a great privilege for the strong to have double the choices of the weak. They must use this gift wisely by considering how their choices affect the sensitive consciences of their brothers and sisters.

In this principle, Paul shows an astute understanding of how conscience works. As we said, one of the two great principles of human conscience is “obey it.” To get into the habit of disobeying conscience can jeopardize one’s eternal destiny (1 Tim. 1:19). This truth leads Paul to spend half of Romans 14 and half of 1 Corinthians 8 on the stumbling-block principle: Christians with a strong conscience must not allow their freedom to embolden a weaker brother or sister to sin against their conscience.

The concern here is not merely that your freedom may irritate, annoy, or offend your weaker brother or sister. If a brother or sister simply doesn’t like your freedoms, that’s their problem. But if your practice of freedom leads your brother or sister to sin against their conscience, then it becomes your problem. We should never bring spiritual harm to others (see also vv. 20–21).

So, how might your use of freedom bring spiritual harm to other professing believers? Paul isn’t clear here, but Doug Moo in his commentary on Romans suggests “two main possibilities”:

[1] Our engaging in an activity that another believer thinks to be wrong may encourage that other believer to do it as well. They would then be sinning because they’re not acting “from faith” (v. 23). . . .

[2] An ostentatious flaunting of liberty on a particular matter may so deeply offend someone that he or she may turn from the faith altogether. (468)

True, we must never allow the conscience of others to determine our own conscience, since the most important principle of conscience is that God is the Lord of conscience. But we must always consider the conscience of others when we determine our own actions.

8. Disagreements about eating and drinking are not important in the kingdom of God; building each other up in righteousness, peace, and joy is the important thing (Rom. 14:16–21).

“So do not let what you regard as good be spoken of as evil. For the kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking but of righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit. Whoever thus serves Christ is acceptable to God and approved by men. So then let us pursue what makes for peace and for mutual upbuilding. Do not, for the sake of food, destroy the work of God. Everything is indeed clean, but it is wrong for anyone to make another stumble by what he eats. It is good not to eat meat or drink wine or do anything that causes your brother to stumble.”

There’s something striking and truly counterintuitive about Paul’s reasoning here and in 1 Corinthians 8:8. Paul appropriates an argument that the strong want to use for their side—that what we eat or drink doesn’t matter to God so quit making a big deal about it—to instead chasten the strong. Since food and drink do not commend us to God, and are not matters of importance in the kingdom of God, then why not voluntarily abstain if your freedom could harm the faith of a wavering Christian? Fortunately, we rarely encounter this decision, but we have to be willing to make it.

Paul mentions just “eating and drinking” in verse 17, but this principle extends to many other disputable matters. The kingdom of God is not a matter of schooling choices, political par- ties, musical styles, and so on. Once again, we’re not suggesting that third-level matters are unimportant. We have some strong opinions on them. But they’re not what the kingdom of God is about. Schismatically dividing over these less important matters does not make “for peace and for mutual upbuilding” (Rom. 14:19).

At the same time, we must note that allowable conscience disagreements do not extend to first-level matters that are central and essential to Christianity. For example, there are some who want to insist that the morality homosexual sexual activity is a disputable issue, even though Scripture and 3500 years of interpretation say it’s not.

9. If you have freedom, don’t flaunt it; if you are strict, don’t expect others to be strict like you (Rom. 14:22a).

“The faith that you have, keep between yourself and God.”

This sentence makes it clear that “faith” in Romans 14 is confidence of conscience. We are most definitely not supposed to keep our faith in the gospel to ourselves!

Not flaunting our opinions applies equally to the strong and the weak. To those with a strong conscience you have much freedom in Christ, but don’t flaunt it or show it off in a way that may cause others to sin. Be especially careful to nurture the faith of young people and new Christians.

Those of you with a weak conscience in a particular area also have a responsibility not to “police” others by pressuring them to adopt your strict standards. You should keep these matters between yourself and God.

10. A person who lives according to their conscience is blessed (Rom. 14:22b–23).

“Blessed is the one who has no reason to pass judgment on himself for what he approves. But whoever has doubts is condemned if he eats, because the eating is not from faith. For whatever does not proceed from faith is sin.”

God gave us the gift of conscience to significantly increase our joy as we obey its warnings. Again, one of the two great principles of conscience is to obey it. “Paul judges it dangerous for Christians to defy their consciences, because if they get in the habit of ignoring the voice of conscience, they may ignore that voice even when the conscience is well informed and properly warning them of something that is positively evil” (D. A. Carson, The Cross and Christian Ministry: An Exposition of Passages from 1 Corinthians , 123).

11. We must follow the example of Christ, who put others first (Rom. 15:1–6).

“We who are strong have an obligation to bear with the failings of the weak, and not to please ourselves. Let each of us please his neighbor for his good, to build him up. For Christ did not please himself, but as it is written, ‘The reproaches of those who reproached you fell on me.’”

This principle doesn’t mean that the strong have to agree with the position of the weak. It doesn’t even mean that the strong can never again exercise their freedoms. On the other hand, neither does it mean that the strong only put up with or endure or tolerate the weak. For a Christian, to “bear with” the weaknesses of the weak means that you gladly help them by refraining from doing anything that would hurt their faith.

Romans 15:3 emphasizes the example of Christ. We cannot even begin to imagine the freedoms and privileges that belonged to the Son of God in heaven. To be God is to be completely free. Yet Christ “did not please himself” but gave up his rights and freedoms to become a servant to the Jewish culture so that we could be saved from wrath. Compared to what Christ suffered on the cross, to give up a freedom like eating meat is a trifle indeed.

12. We bring glory to God when we welcome one another as Christ has welcomed us (Rom. 15:7).

“Therefore welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you, for the glory of God.”

With this sentence, Paul bookends this long section that began with similar words in 14:1. But here in 15:7 Paul adds a comparison—“as Christ has welcomed you”—and a purpose—“for the glory of God.” It matters how you treat those who disagree with you on disputable matters. When you welcome them as Christ has welcomed you, you glorify God.